Bayonet Rule Was the Birth of Freedom

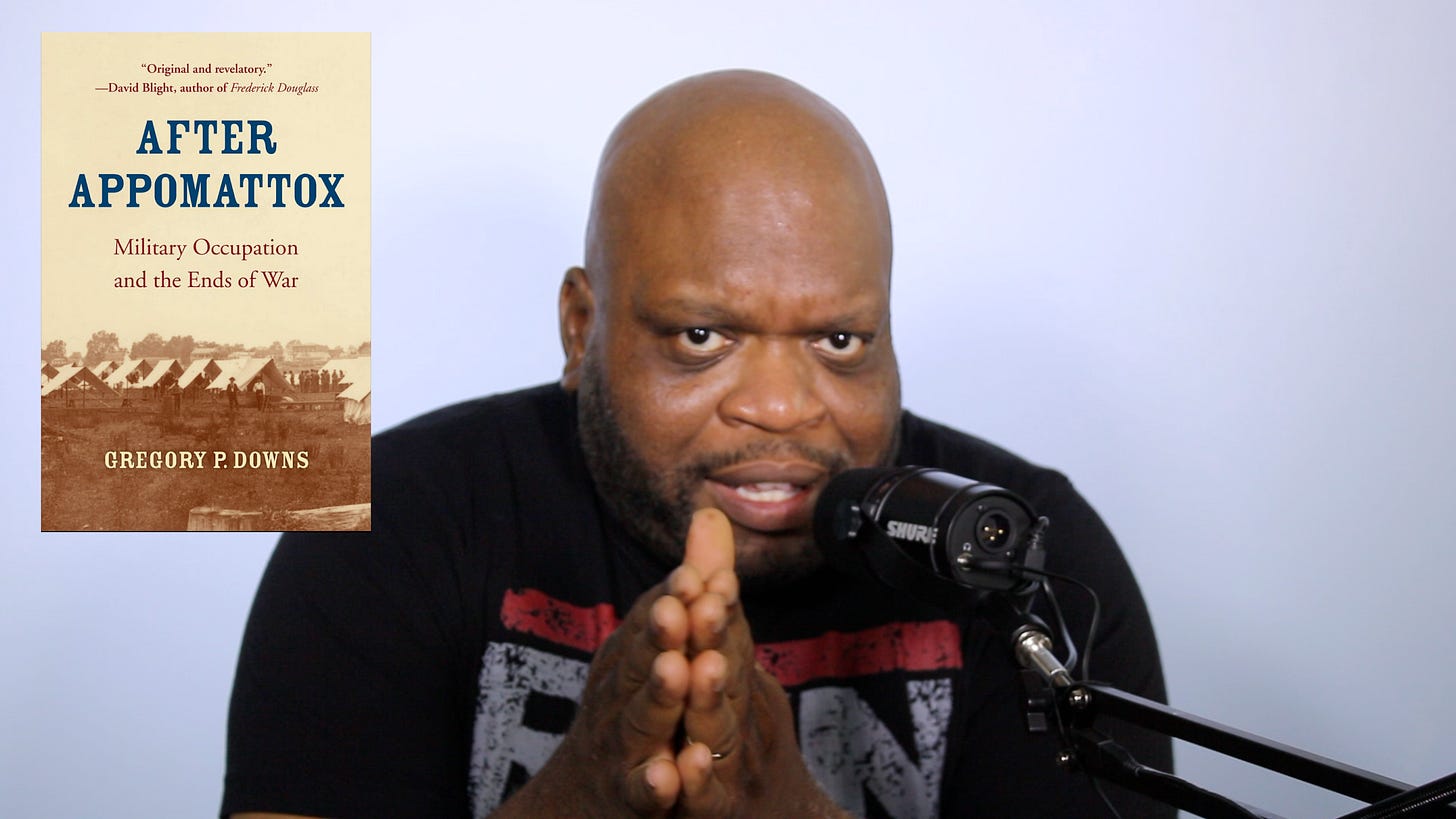

Revisiting Gregory P. Downs’ After Appomattox Through the Lens of the Blues

Gregory P. Downs doesn’t write history like a bedtime story. His book After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War rips the Band-Aid off America’s favorite myth: that the Civil War ended neatly in April 1865. Downs shows us the truth which is that what followed was not peace but a military occupation, and that occupation was the only thing that made freedom real .

This book shook me so deeply that years later, when I made my documentary Striking a Chord with the Devil, I used Downs’ research as one of the pillars holding up the video. Because if you don’t understand that the “after-war” was still war, you don’t understand the birth of the blues.

Frame capture from my YT documentary Striking A Chord With The Devil

Martial Law Gave Us Freedom

Downs’ core claim is both simple and devastating: the rights we take for granted—due process, equal protection, birthright citizenship, even the vote—were by-products of martial law . Freedom had to be enforced with soldiers at the courthouse door, soldiers in the fields, soldiers standing between freedpeople and the planters who swore slavery would be back in eighteen months .

That’s why I leaned on this book for the doc. The blues isn’t just music about heartbreak; it’s a record of what happens when the only shield between you and bondage is the Army. When I cut scenes of freedpeople singing to survive, I was thinking of Downs’ argument: rights weren’t granted, they were hammered out at bayonet point.

Insurgency Never Stopped

One of the most chilling parts of Downs’ account is how quickly ex-Confederates regrouped. They didn’t surrender their ideology at Appomattox; they just went home, cleaned their guns, and waited . Soon they were launching insurgencies—ambushing freedpeople, assassinating teachers, and toppling Black governments.

Reading those passages years ago gave me the language to frame the through-line in my documentary: the war never ended. It just shifted battlefields—from Gettysburg to courthouse steps, from plantations to night rides. That’s the soil out of which the blues grew.

Bayonet Rule or No Rule at All

Downs doesn’t mince words: Reconstruction was an occupation. Soldiers closed newspapers, arrested civilians, even replaced mayors . White Southerners called it “bayonet rule.” Black Southerners called it hope. They didn’t want less government; they wanted government strong enough to protect them .

That paradox of coercion as liberation is exactly what gives the blues its tone. Survival music born from contradiction. Downs writes: “The fruit of occupation was freedom, no matter how limited its terms” . In my film, I tried to translate that line of thought into sound: you don’t get Robert Johnson at the crossroads unless you first had Mississippi under armed occupation, teaching Black people that rights only matter if power defends them.

The Perils of Peace

Downs makes it clear what happened when the soldiers left. Northern voters lost their will, Congress pulled back, and white Democrats declared the end of “bayonet rule.” What really ended was rights. The Klan surged, Jim Crow followed, and by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, the dreams of Reconstruction were gutted .

His warning still lands like a gut punch: “A government without force means a people without rights.” That’s not abstract theory—it’s the blues in one sentence.

Why Downs Still Matters

I didn’t stumble on Downs after making my film—I built the film because of Downs. After Appomattox gave me the language to connect Reconstruction’s unfinished war with the creation of America’s first great art form. Every insight in the doc, every argument about freedom wrestled from violence, traces back to this book.

So if you want to understand why the blues sounds the way it does, or why American democracy has never quite worked the way it promised, read Downs. Because behind every bent note is the same unresolved truth: Appomattox wasn’t peace. It was the beginning of bayonet rule and without bayonet rule, there would have been no freedom to sing about.

Every blues line is a prayer and a protest at once. First you moan it, then you sing it, then you pass it on. If this piece hit you in the gut, don’t just nod and scroll. Join us—add your voice to the chorus that refuses to be silenced.

James Baldwin would be proud of you!

WOW !!! Thank you...