BREAKING: Massie claims DOJ hid 6 Epstein names

Massie says the names were still blacked out in the “unredacted” files. Khanna read six names on the House floor the next day. What’s confirmed, what’s unclear, and why it matters.

Quick read

Rep. Thomas Massie (R‑KY) says the Justice Department is still hiding names in the newly released Epstein files.

He says he and Rep. Ro Khanna (D‑CA) reviewed “unredacted” files in a DOJ reading room and found that at least six men’s names were still blacked out.

Massie said those names were “likely incriminating” because they showed up in the records, and he said it took “some digging” to find them. [2][7]

Massie and Khanna did not name the men right away.

The key twist: names got read on the House floor

The next day, Khanna read six names on the House floor after reporting said DOJ removed more redactions. [6][9][10]

That move matters because speaking on the House floor can give lawmakers extra legal protection under the Speech or Debate Clause. [13][14]

In plain English: it’s one way to say something publicly without being dragged into court for it as easily.

The six names that were reported

Multiple outlets reported the same six names Khanna read: [6][9][10]

Leslie Wexner

Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem

Nicola Caputo (identity contested)

Salvatore Nuara

Zurab Mikeladze

Leonic Leonov

Why this is hard to verify

Regular people cannot easily check what Massie and Khanna saw.

Lawmakers reviewed the files under tight rules (no electronics and handwritten notes). [3][7]

Also, some DOJ materials are behind age‑verification and the public record can be hard to search.

So the big public fight is about this question. Are these redactions protecting victims and investigations, or protecting powerful people?

One more complication

A man named Nicola Caputo in Italy publicly denied he is the same “Nicola Caputo” named in the files. [8]

That shows a real risk here: if you release a name without strong identifiers, you can hit the wrong person.

What DOJ says

DOJ says it complied with the Epstein Files Transparency Act and describes a huge review process with millions of pages. [1][4]

Critics say DOJ still left out things or over‑redacted.

Why this matters

This is not just gossip.

It is a fight over whether the government is following the law on transparency.

And it is also a fight over how to do transparency without harming victims or falsely accusing people.

What this report covers

This report looks at the “name drops” episode involving Rep. Thomas Massie (R‑KY). It sits inside the Justice Department’s ongoing releases under the Epstein Files Transparency Act (EFTA).

The timeframe here is the last 30 days (roughly Jan 12–Feb 11, 2026). Older references appear only when they help explain the law or the records.

The basic sequence, step by step

Here is the core sequence that shows up across major reporting.

Massie and Khanna reviewed DOJ “unredacted” Epstein files.

Massie said he found that at least six men’s names were still redacted, even in what lawmakers were told were “unredacted” materials.

Massie said those names were “likely incriminating” because of how they appeared in the records.

Massie and Khanna initially declined to name the people publicly.

The next day, Khanna read six names on the House floor after reporting said DOJ removed additional redactions.

Massie also pushed public pressure through social media and public remarks as part of the effort to force more unredactions.

The biggest open problem for the public

There is a key uncertainty that does not go away.

Most readers cannot independently check the underlying DOJ documents behind the “six men” claim.

Members of Congress reviewed materials under strict access rules (no electronics, handwritten notes).

Some documents referenced by outlets sit behind DOJ’s age‑verification gate, and some were described secondhand rather than fully reproduced.

Because of that, claims about what a name’s appearance “means” (for example, “co‑conspirator,” “likely incriminating,” or “protected”) do not all have the same weight.

What “drop names” means

Massie didn’t actually “drop names” in the way people are using that phrase online. What he did was say that when he and Rep. Ro Khanna reviewed the DOJ’s “unredacted” Epstein material, they still found at least six men’s names blacked out, and Massie described those names as “likely incriminating.” At first, neither of them publicly identified the men. Then, after reporting said DOJ removed additional redactions, Khanna read six names on the House floor, putting them into the Congressional Record. So the accurate fact pattern is: Massie raised the redaction issue and hinted at naming if DOJ didn’t fix it, and Khanna later publicly read the names.

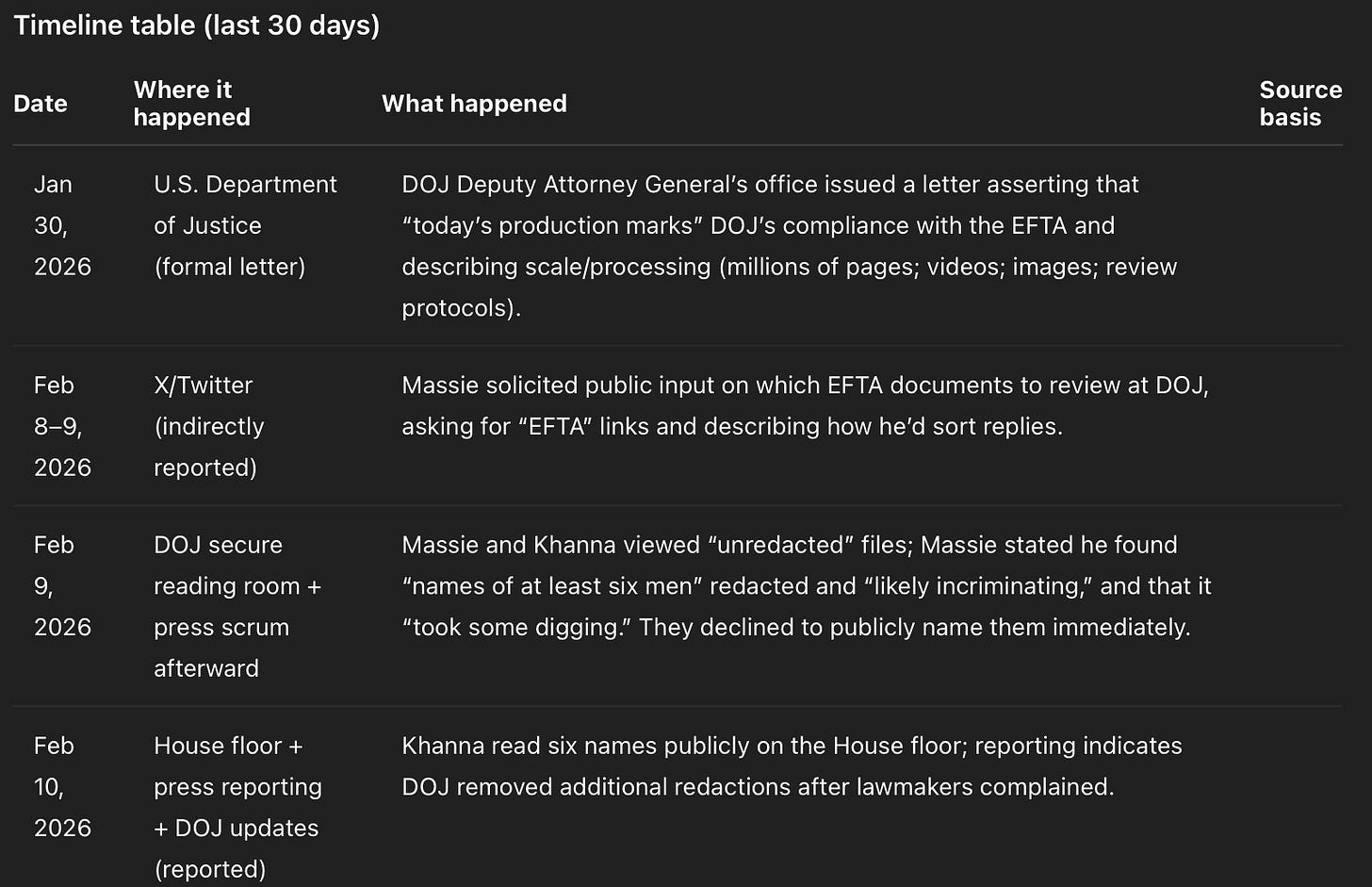

Timeline and where the story moved

Below is a consolidated timeline of the key moves, with dates and venues.

Who was named and why it matters

The six reported names

Multiple major outlets report Khanna named six men publicly after the DOJ review:

Leslie Wexner

Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem

Nicola Caputo (identity contested; see below)

Salvatore Nuara

Zurab Mikeladze

Leonic Leonov

A key caveat appeared in careful reporting: being named in the files is not, by itself, proof of criminal wrongdoing, and Khanna did not allege specific crimes by these individuals in the cited accounts.

Why some names land harder than others

Wexner: Wexner stands out because his ties to Epstein have been widely reported for years, including a financial‑management relationship. In this episode, the fresh hook is reporting that a 2019 FBI document referred to him as a “co‑conspirator.” That language sounds legal, even if it did not become a charge. CBS also reported that a legal representative said a federal prosecutor told Wexner’s counsel he was viewed as an information source and “not a target,” and that he was never charged.

Bin Sulayem: Bin Sulayem stands out because he is described as the CEO of DP World (a major ports and logistics company) and because coverage points to specific communications linked to him (including an email described as coming from him to Epstein and another described as from Epstein to him). Within what is publicly described, this is one of the clearer examples where “named in files” is connected to a concrete document reference.

Caputo: Caputo matters because it shows how messy “name‑only” disclosures can get. Major reporting says a “Nicola Caputo” was in the named set, but Italian reporting (ANSA) quoted the Italian political figure Nicola Caputo saying he is not the person referenced and describing reputational fallout, plus plans to seek clarification through the U.S. embassy. That is a live example of misidentification risk when a name is released without strong identifiers.

Nuara, Mikeladze, Leonov: These names draw attention for a different reason. They highlight the “unknowns” problem: the public cannot easily evaluate who they are, whether they are correctly identified, or what their appearance in the files actually means. The Guardian noted limited public information, and CBS reported DOJ said four of the six appear only in one document.

What we can say with confidence, and what we can’t

What is strongly supported

These points are well supported because they are tied to direct quotes, official documents, or consistent reporting across outlets.

Massie said he found at least six men’s names still redacted and called them “likely incriminating,” and he said it took “digging.”

The EFTA sets the rule book: it orders disclosure of categories of Epstein‑related DOJ materials within 30 days, bars withholding based on embarrassment/reputation/political sensitivity, allows certain narrow withholdings, and requires a report to Congress within 15 days of completion listing what was released/withheld and summarizing redactions. [1]

DOJ’s Jan 30 letter (Deputy AG office) asserted compliance and described the scale of review: “more than 500 attorneys and reviewers,” “more than 6 million pages” potentially responsive, and a production totaling “nearly 3.5 million pages” when combined with prior releases (as described in the letter). [4]

What is plausible but hard for the public to prove

Massie’s “likely incriminating” claim is best understood as a lawmaker’s interpretation, not a settled legal finding. From the public record alone, readers often cannot tell whether names appear in a way that suggests wrongdoing, or in a more incidental way (contacts, scheduling, third‑party mentions).

Reports say DOJ removed some redactions after lawmakers complained, but many readers cannot do an easy “before and after” document comparison because of access gates and the size of the archive.

Where reports agree and where they clash

There is strong agreement on the basic sequence: review, complaint about redactions, then public naming.

There is also agreement on strict reading‑room limits (no electronics, handwritten notes), which makes it harder to publish full primary documentation from the members’ review.

The tension shows up between DOJ’s “we complied” posture and claims from critics that the release was incomplete or over‑redacted. Axios reported watchdog concerns and DOJ pushed back, calling it a “tired narrative” while citing the page totals.

Caputo’s denial (ANSA) is a direct clash with the assumption many people make when they hear a name publicly: that it automatically points to a single, clearly identified person.

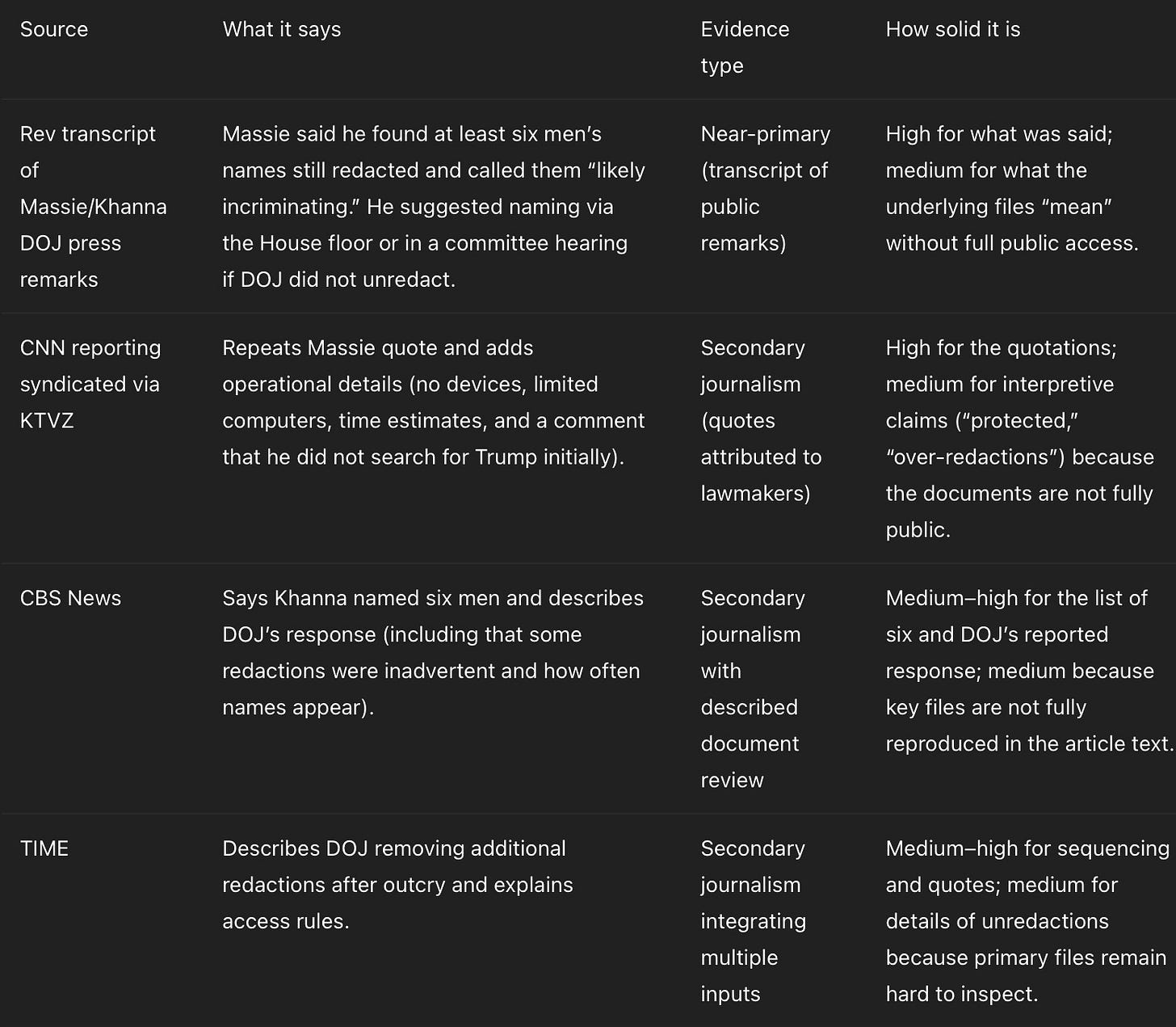

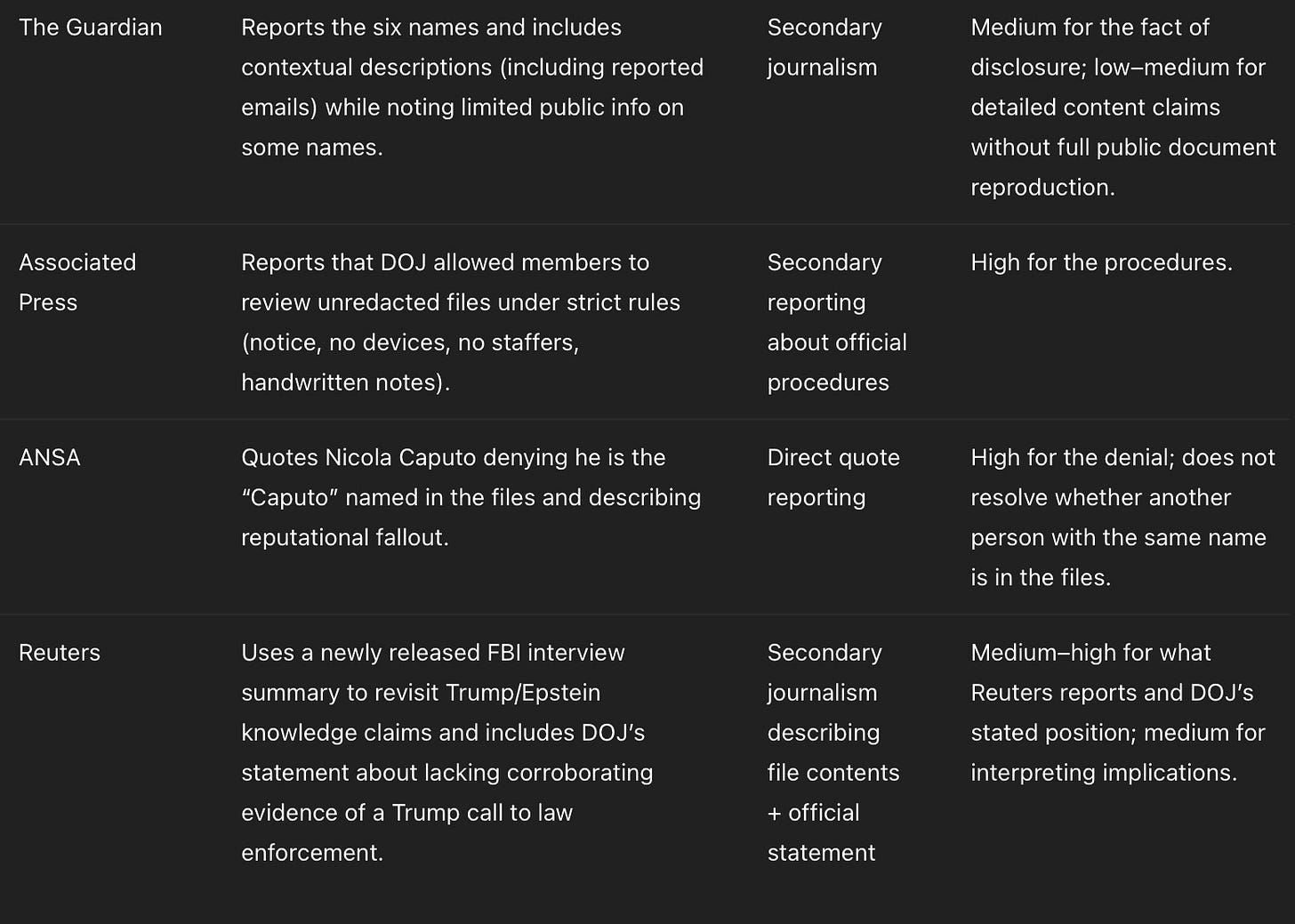

How strong are the sources in this episode

This table lays out what major sources said, what kind of evidence they used, and how solid the claim is.

The politics and the law underneath this

Why the transparency law matters

The EFTA creates a clear compliance frame.

Broad disclosure is mandatory.

Certain reasons for withholding are explicitly prohibited.

Congress is owed a post‑release report detailing what was released and what was withheld, plus the legal basis for redactions.

That makes over‑redaction a bigger story than “lack of transparency.” Lawmakers can argue it is noncompliance with the statute.

At the same time, DOJ’s own protocols stress victim protection and include specific categories (including FBI “302s”), which is why so much of this fight comes down to what counts as an allowed redaction and what was already redacted upstream before DOJ posted anything.

Why “naming from the floor” is a tactic

Massie linked disclosure to speaking “from the floor or in a committee hearing.”

That points to the Speech or Debate Clause, which says members cannot be questioned elsewhere for speech and debate in either House.

The practical point is simple: naming people on the House floor is not just theater. It is a strategy designed to reduce exposure to civil lawsuits like defamation by putting the statement inside a protected legislative setting.

The harm problem: victims and mistaken identities

There is a second controversy running alongside this.

Survivor advocates criticized DOJ for failing to properly redact victim‑identifying information in some releases. Reporting says DOJ temporarily pulled thousands of documents to correct mistakes. [15]

So lawmakers are pushing in two directions at once: fewer redactions for alleged perpetrators, but stronger redactions for victims.

Caputo’s denial is a second warning sign. Even if a disclosure is legal, identity ambiguity can create reputational harm without due process. That is not an argument against transparency. It is an argument for context and identifiers, because “a name” is not the same as “a proven claim.”

How the media framed it, and what Massie’s pattern looks like

The main frames in coverage

Different outlets emphasized different angles.

A compliance frame: some coverage focused on the statute and DOJ’s response.

A confrontation frame: some coverage focused on lawmakers forcing action through public pressure.

A sensation frame: some accounts highlighted lurid details, which can blur the line between “named in a file” and “proven wrongdoing.”

A credibility frame: some coverage emphasized what the files say versus what officials deny.

Massie’s pattern in this episode

Over the last 30 days, Massie showed a consistent approach.

He crowdsourced which documents to examine, using public attention as a tool.

He said he wanted DOJ to fix over‑redactions first, but kept an escalation option open: name people from hearings or the House floor.

He repeatedly anchored his argument in the EFTA’s rules, framing this as a compliance question, not just a partisan fight.

Primary materials worth citing

If you are writing or broadcasting about this episode, these are the cleanest, most “citation‑efficient” building blocks:

The EFTA itself (for deadlines, prohibited withholding grounds, allowed redactions, and the 15‑day report‑to‑Congress requirement).

DOJ’s Jan 30 compliance/production letter (for DOJ’s own claims about scope, staffing, and totals).

DOJ “First Level Review Protocol” (for how DOJ instructed reviewers to decide what is responsive and what should be redacted, including FBI “302s”).

The Massie/Khanna transcript (for the “six men” claim, “digging,” and the floor/committee disclosure rationale).

Speech‑or‑Debate texts and summaries (Constitution Annotated and Supreme Court discussion, for the legal shield concept).

ANSA’s report on Caputo’s denial (as a concrete example of misidentification risk).

Support this work

Breaking news like this does not come from a newsroom budget. It comes from me chasing the paper trail in real time, cross‑checking the claims, and writing fast without cutting corners.

If you want more posts like this, become a paid member. Your subscription is what keeps this independent, sponsor‑free, and willing to pull the thread when the story gets uncomfortable.

If you cannot upgrade right now, a restack and share still helps. It tells the algorithm this kind of reporting matters.

Sources (plain text hyperlinks)

https://www.congress.gov/119/plaws/publ38/PLAW-119publ38.pdf

https://www.rev.com/transcripts/massie-and-khanna-on-epstein-files

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/massie-khanna-epstein-files-6-men/

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/10/six-men-epstein-files-unredacted

https://time.com/7373333/epstein-files-redactions-massie-khanna-trump/

https://www.axios.com/2026/02/06/epstein-bondi-patel-records-withheld

https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/article-1/section-6/clause-1/

https://www.businessinsider.com/doj-jeffrey-epstein-removed-thousands-files-2026-2

It’s pretty obvious Wexner coroperated and gave all of the evidence to prosecutors of Jeffrey Epstein and he got immunity or a plea deal to do it. He was the mastermind he cororaberates all of the evidence against Jeffrey Epstein because he financed it. He can verify all the banking information. They cut a deal with a Monster. I hope he’s still bought to Justice. But Wexner is the co conspirator of a child sex trafficking ring. He was right next to Jeffrey Epstein. Him and Epstein are equal. All that Venom you got towards Epstein take that to Wexner. Maxwell is in a prison camp Wexner walks free he’s just as guilty as Maxwell. He got money power and privilege. Wexner is the star witness against Epstein and Maxwell he put them in jail. And made sure he stayed out of jail. I don’t know how get got that deal. But if R. Kelly got put in jail. Les Wexner needs to rot in jail.

Excellent info, framing, and balance.