BREAKING: Rev. Jesse Jackson Dies At 84

The civil rights icon whose campaigns helped make Obama possible.

I was 12 in 1984, and my room had a rhythm to it. The record player was working overtime, Michael Jackson’s album spinning until I wore the groove thin, especially “P.Y.T.” MTV lived near the top of my channel list, because it felt like the future. CNN was up there too, because my house had adults who kept one eye on the world, even when the world was heavy.

That spring, the future and the heavy kept colliding on my TV. In between videos and school nights, I kept seeing the same man: Rev. Jesse Jackson, voice rising like a sermon, talking about dignity and jobs and a country that still didn’t know what to do with Black ambition that refused to shrink. I did not have the vocabulary for “coalition politics” or “civil rights legacy.” I only knew I was watching somebody insist that the presidency was not a whites-only imagination, and he was doing it on television where kids like me could see it.

Updated: Feb. 17, 2026

Rev. Jesse Louis Jackson Sr., the preacher-activist who marched in the civil rights era, built institutions for economic justice, and ran for president twice in campaigns that helped set the stage for Barack Obama, died Tuesday, Feb. 17, 2026. He was 84.

His family said he died peacefully surrounded by relatives. The immediate cause of death was not disclosed. Jackson had faced serious health challenges in recent years, including progressive supranuclear palsy.

This is a developing story and will be updated.

At a glance

Born: Oct. 8, 1941, Greenville, South Carolina

Known for: Civil rights leadership, Operation Breadbasket, founding Operation PUSH and the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition

Presidential runs: Democratic primaries in 1984 and 1988

Notable recognition: Presidential Medal of Freedom (2000)

Family: Survived by his wife, Jacqueline, and six children

For more than half a century, Jackson stood at a uniquely American intersection: pulpit thunder and precinct math, moral witness and coalition arithmetic. A protégé of Martin Luther King Jr., he became a national figure by pushing civil rights into the arena of jobs, contracts, and political power, then by building organizations that translated protest into sustained pressure.

Jackson’s central historical role is often described as “keeping hope alive,” a phrase that became both sermon refrain and political program. But his deeper contribution may be this: he made it normal, on national television and inside party politics, to imagine a Black candidate seeking the presidency on something larger than symbolism. His 1984 and 1988 campaigns expanded the electorate, tested the boundaries of possibility, and helped write the coalition blueprint that Obama would later refine into a winning national majority.

As news of his death spread, tributes began arriving from political leaders and civil rights veterans who viewed Jackson as a bridge between the movement generation and the modern era of national Black political power.

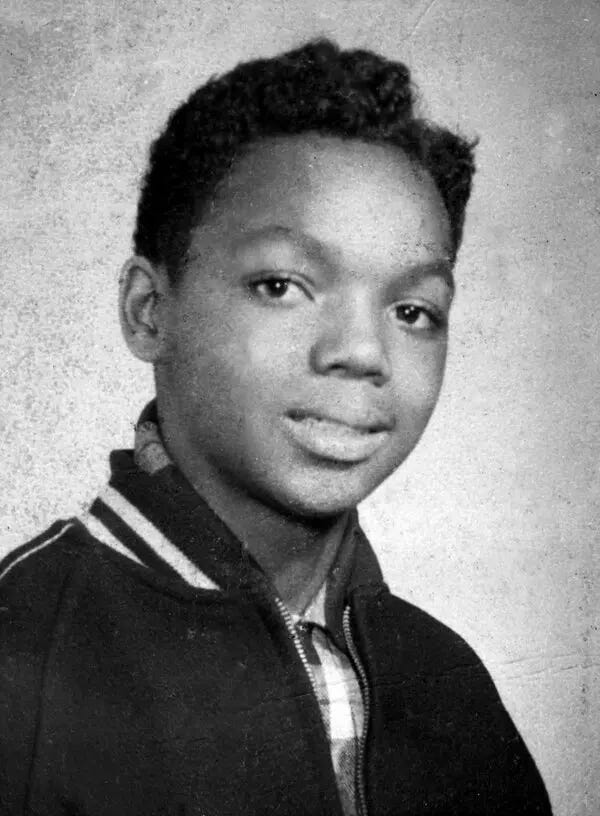

From segregated South Carolina to King’s inner circle

Jackson was born Oct. 8, 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, and grew up in the thick air of Jim Crow, an atmosphere that did not require theory to teach a child what power looked like. He attended college in North Carolina, then moved to Chicago for graduate theological study, where the civil rights movement’s moral drama was being translated into urban organizing and economic leverage.

His early national prominence came through the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Operation Breadbasket, the SCLC’s economic arm. Breadbasket’s logic was straightforward: if Black communities supplied the customers, Black workers and Black businesses should share the jobs and contracts. Jackson became a leading figure in that work, embracing the movement’s insistence that civil rights without economic rights was a half-built house.

After King was assassinated in Memphis in 1968, Jackson was suddenly treated by parts of the press as a possible heir to King’s public mantle, a framing that both elevated and complicated him. He remained with SCLC for several years, then in 1971 founded People United to Save Humanity, later known as People United to Serve Humanity: Operation PUSH.

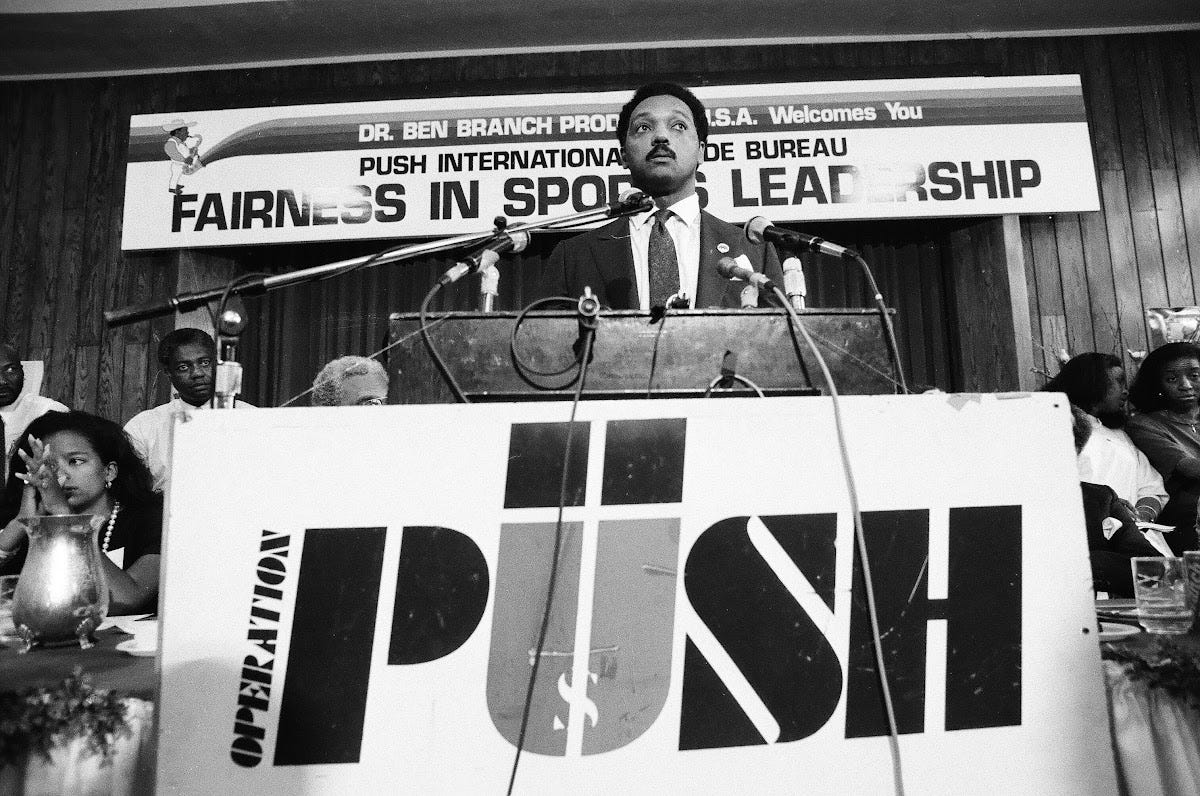

PUSH, boycotts, and the politics of economic pressure

PUSH quickly became known for highly visible campaigns that mixed negotiation with confrontation, particularly corporate boycotts aimed at hiring, supplier diversity, and fair treatment of Black consumers. Jackson’s critics called it theatrical; supporters called it accountability with teeth. Either way, it was a template: a civil rights strategy that treated boardrooms and ad budgets as battlefields alongside legislatures and courts.

In 1984, Jackson founded the National Rainbow Coalition, an explicit attempt to stitch together constituencies commonly invited to Democratic speeches but rarely centered in Democratic power: Black voters, Latinos, working-class whites, farmers, labor, women, and, notably for the era, gay and lesbian Americans. That coalition later merged with PUSH in 1996 to form the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition.

The presidential runs that changed what “possible” felt like

Jackson announced his first run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1983. He was initially dismissed by much of the establishment as a protest candidate. Then he began to win delegates, rack up votes, and demonstrate a national appeal that forced the party to look directly at a new reality: Black political leadership did not have to wait its turn.

In 1984, Jackson won millions of votes and helped register roughly a million new voters. In 1988, he won several primaries and finished second in primary voting behind Michael Dukakis, delivering a convention address remembered for its sermon-like sweep and the language of a “rainbow” America.

Those campaigns mattered for reasons that look clearer in hindsight than they did in the moment. They tested the electorate’s capacity to imagine a Black president not as an exceptional token but as a governing possibility. They pushed the Democratic Party’s internal rules and incentives toward broader inclusion. And they offered a vocabulary of coalition politics that Obama later refined into a winning map. Less revival-tent cadence, more professorial calm, but built on a similar architecture: expand the electorate, widen the “we,” and make moral aspiration feel practical.

A global negotiator and a complicated public figure

Jackson’s influence was not confined to domestic politics. He at times played an informal diplomatic role, including efforts that helped secure the release of detainees abroad, actions that critics sometimes derided as freelancing and supporters described as humanitarian bargaining power in motion.

Like many long-lived public figures, Jackson’s legacy is not a simple halo. He was a master of the spotlight, and he drew criticism over the decades for the ways attention gathered around him. Yet even many who questioned his style conceded the historic substance: he made American democracy widen in real time, by force of voice, organization, and relentless insistence that excluded people were not a footnote but the text.

Health struggles in later years

In 2017, Jackson disclosed that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, saying he had been living with it since 2015. In later years, his condition was described as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a rare neurodegenerative disorder often mistaken for Parkinson’s earlier in its course.

He stepped back from day-to-day leadership as his health declined, but remained a potent symbol. His very presence recalled an era when the civil rights movement’s leaders were both organizers and orators, both moral voices and tactical strategists.

Honors, survivors, and the road he opened

Jackson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2000, a mainstream recognition of a career that had often been a thorn in the side of mainstream power.

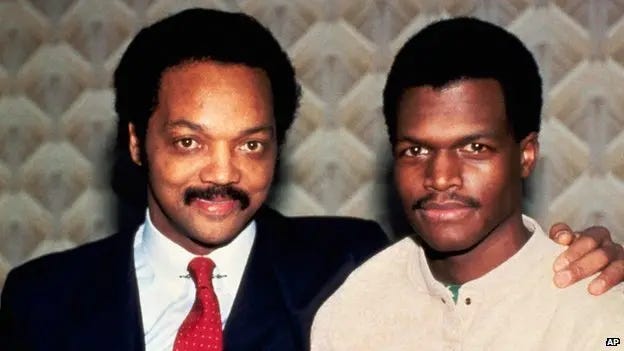

He is survived by his wife, Jacqueline, and their children, including Santita Jackson and former Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr., among others.

In the years after Obama’s election, it became common to narrate American progress as an inevitable arc. Jackson never quite treated it that way. His whole style, pulpit urgency, street-level confrontation, coalition-building, assumed that history does not “bend” on its own. It has to be leaned on.

And that may be his cleanest link to Obama: not simply that he ran before Obama ran, but that he changed the emotional rules of the room. Back when I was 12, flipping from MTV to CNN with “P.Y.T.” still ringing in my ears, he kept showing up in the middle of the broadcast like a stubborn fact. Year after year, he made it harder for America to pretend it could not imagine what it would later watch on a November night in 2008: a Black family walking onto a victory stage, not as a miracle, but as a culmination.

Sources

Associated Press (AP News), “The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who led the Civil Rights Movement for decades after King, has died at 84” (Feb. 17, 2026): https://apnews.com/article/43abb84d2ffc76d967f9a5596ebd0be1

Reuters, “Jesse Jackson, civil rights leader and US presidential hopeful, dies at 84” (Feb. 17, 2026): https://www.reuters.com/world/us/jesse-jackson-civil-rights-leader-us-presidential-hopeful-dies-84-nbc-news-2026-02-17/

TIME, “Jesse Jackson, Civil Rights Leader and Presidential Hopeful, Dies at 84” (Feb. 17, 2026): https://time.com/7379080/jesse-jackson-civil-rights-leader-dies-at-84/

The Guardian, “Jesse Jackson, civil rights leader, dies aged 84” (Feb. 17, 2026): https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/17/jesse-jackson-civil-rights-icon-dies

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Jesse Jackson | Civil Rights, Health, Accomplishments, & Facts”: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jesse-Jackson

Stanford (King Institute), “Jackson, Jesse Louis”: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/jackson-jesse-louis

Rainbow PUSH Coalition, “Brief History”: https://www.rainbowpush.org/brief-history

Rainbow PUSH Coalition, “Organization and Mission”: https://www.rainbowpush.org/organization-and-mission

Parkinson’s Foundation, “Jesse Jackson Diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease” (Nov. 17, 2017): https://www.parkinson.org/about-us/news/reverend-jesse-jackson-diagnosed-with-parkinsons-disease

APDA (American Parkinson Disease Association), “Understanding PSP in Light of Rev. Jesse Jackson’s Diagnosis” (Nov. 19, 2025): https://www.apdaparkinson.org/article/understanding-psp-in-light-of-rev-jesse-jacksons-diagnosis/

AFTD (Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration), “Rev. Jesse Jackson… diagnosed with PSP” (Nov. 13, 2025): https://www.theaftd.org/posts/1ftd-in-the-news/jesse-jackson-psp/

The American Presidency Project (UCSB), “Remarks on Presenting the Presidential Medal of Freedom” (Aug. 9, 2000): https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-presenting-the-presidential-medal-freedom-0

Clinton White House Archives, “Statement by the Press Secretary on the Presidential Medal of Freedom” (Aug. 3, 2000): https://clintonwhitehouse6.archives.gov/2000/08/2000-08-03-statement-by-press-secretary-on-presidential-medal-of-freedom.html

Always a fighter for a just society.

Rest in peace Reverend Jackson, you deserve it!🥲

A life well lived, sir.