If You Think You’re Lonely Now, Blame Austerity

Bobby Womack and the blue-collar squeeze from 1982 to the gig grind.

I wanna dedicate this to all the lovers of prose tonight.

Might be the whole world tonight.

Everybody needs a writer to love.

When it’s cold outside, what are you reading?

Let me talk about this woman of mine.

Y’all back me up, alright?

She says I ain’t got pages.

When I do, they’re late.

On time, and Stripe account is empty.

She points at other writers with tight structure, clean rollouts, book deals.

But I can’t be in two places at one time.

If you think you ain’t got nothing to read now, wait until tonight.

Relax. That wasn’t me running “authentic” game on you. Okay, a little Bobby in the cadence. Truth is I’m tired. I cannot use it as an excuse anymore. You show up at work even when you are tired, so I’m showing up for work here.

This isn’t a personal blog anymore. It’s community property. You own this. Paid or free, I work for you. Not some shadowy 1620 outfit. Not a sponsor breathing down my neck while I pretend I love a wack product because that bag of Benjamins looked pretty in my bank account.

I told my partner retirement meant more time with her. Then I wrote through the night. When I’m not writing, I’m worrying about what to write next. That can make a person feel alone when you’re three feet away. Bobby knew that curse. A voice big enough to fill a room and still leave someone lonely in the bed.

So here’s my vow tonight. Pages that come out of the closet, stand by your side, and follow you around the room. We’re reading Womack as policy felt at home, 1982 to right now.

The cover smiles like Sunday. Big glasses, pinstripes, a kid on his shoulders, a woman leaning in. Jet does what Jet does best: joy as evidence. The headline talks about bouncing back from tragedy and a stalled run. The picture says family anyway. You can feel the church in that grin. You can feel the grind in it too.

He came up poor enough to turn hunger into humor. As he joked, “the neighborhood was so ghetto that we didn’t bother the rats and they didn’t bother us.” That line isn’t just a laugh. It’s how you tell the truth without breaking the room. He learned that tone in the pews. Testify the wound. Sweeten it so people can carry it home. Guitar in the sanctuary. Harmony as a coping skill.

That mix is why blue-collar Black workers heard themselves in him. In ’81 the plants still ran. Not like the decade before, but the line was there. Overtime shrank. Shifts got choppy. You could still put in the work, and you felt the ceiling lowering. Church on Sunday. Locker room on Monday. A steward’s number in your pocket. When he sang like a deacon who’d punched a clock, it rang true. He was raised on call-and-response, so he knew how to answer the foreman and the family with the same voice.

Look at the picture again. The smile is real. The weight is real. That’s the register of a man who learned to hold both. Which is why, when he warned about “tonight,” folks on third shift understood.

“Now comes Miller time.”

The next page has the sun low. Stadium lights tall. Couples strolling out in their work-casual best. In the foreground a giant cold mug, hand wrapped tight, foam high like reward. Bottom corner says 1982. The copy is a promise: you did your hours. Here’s your relief.

This is the blue-collar mirror right across from Bobby. Same decade. Same clock. Ads sold the off-shift as salvation. Finish the game. Finish the shift. Then fix the ache with a beer. You can hear the whistle in that sunset. You can hear the foreman in that grip.

Put it next to Womack and the rhyme jumps out. The ad says, “Now comes tonight.” Bobby says, “Wait until tonight.” One sells an answer for the hour after work. The other tells the truth about what shows up when the house goes quiet. Both know the shop floor still exists in ’81, just thinner. Fewer overtime slips. More strain inside the living room.

Why it matters here: this is how the era taught us to handle shrinkage. Less public care, more private coping. The bar becomes community center. The couch becomes counseling. For a lot of Black workers, church and shift were still the spine, so Bobby’s church-born testimony cut through the commercial gloss. He sounded like the deacon who punched a clock, not the announcer who said everything was fine.

So no, the blue-collar thread isn’t a reach. It’s the layout. On one page, a hymn of survival in a family photo. On the next, a chilled answer to a long day. Same night. Different endings.

Trade, not aid. Right there on the page.

This Jet spread shows an economic playbook, not a vibe check. A civil-rights org signs a five-year pact with a soda company that routes real money and power: a 15 percent Black employment goal including leadership seats, Black-owned ad and travel agencies in the vendor stack, 15 percent of deposits into Black-owned banks, scholarships for HBCU students, the first Black-owned franchise, and a $10 million program to back minority wholesalers. Because Black consumers are pouring serious dollars into the economy, the deal says some of that flow must come back through Black institutions.

Zoom the frame. The same group is pressing the Big Three automakers for parallel commitments. Because union plants still anchor a lot of Black households in ’82, even as overtime shrinks. This is blue-collar leverage in print: negotiate procurement, hiring, deposits, and distribution while the public safety net thins. It is reciprocity over charity. It is receipts.

Now tie it to Bobby. The ad on the last page promised relief after the shift. This page is the chessboard behind that promise. Corporate America markets hard to the living room while activists force terms that send some dollars back to the block. Meanwhile the man in the song hears “her girlfriend’s got…” and feels the squeeze of status goods in a tightening wage world. Church voice meets shop-floor math. That is why the hook lands. “Wait until tonight” is not just a breakup chorus. It is the hour when policy, paychecks, and pride all show up in the same room.

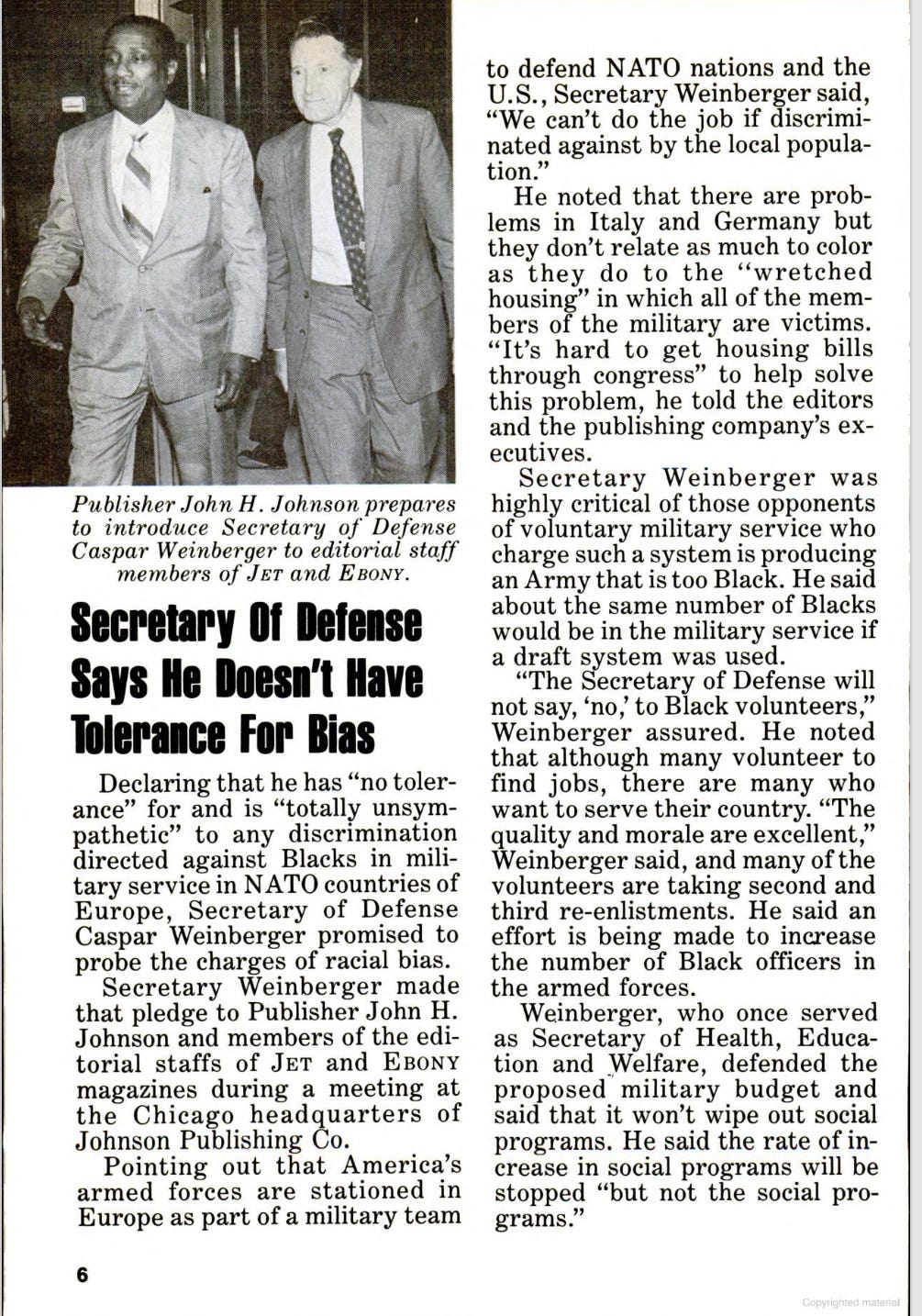

John H Johnson and Defense Secretary Weinberger

Look at this page. John H. Johnson brings in Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger to talk straight to Jet and Ebony. Weinberger says “no tolerance” for bias, promises to probe discrimination, says the housing for troops is “wretched” and needs help, and, crucially, pledges to grow Black officers. He defends the budget but adds they won’t wipe out social programs. That’s a Republican cabinet official, in Black media, saying inclusion out loud.

If those Reagan-era Republicans walked into 2025, they’d be branded RINOs, called “woke,” and primaried by Tuesday. “Increase Black officers”? Today they’d sneer “DEI.” Meeting with Jet and Ebony? They’d call it pandering. “Not wipe out social programs”? Socialist creep. The party we knew is gone; the TV set got replaced by an outrage machine that rewards the boo, not the build.

And that’s the Womack echo. Back then the line was “wait until tonight” and you might still find a ladder in the morning. Now the message to their own moderates is colder: if you think you’re lonely now, wait until tonight. The purge is the point.

Conference room candor.

Top photo: a circle of Black editors in chairs, notepads out, sleeves rolled. A cabinet official sits with them and answers. No podium. No flag wall. Just questions and receipts. He talks bias in the ranks, housing for troops, and even the Middle East in plain terms, noting millions of Palestinian civilians who want peace. That’s not a press release. That’s press.

Bottom photo: the handshake image after the grilling. Smiles, but only after the work. This is what the Black press was at its best in ’82. Church, union hall, and newsroom in one. You could clock out, pick up Jet, and see your editors put power in a chair and make him talk like a neighbor.

Tie it back to Womack. The song names what happens in the house at night. These pages show what happened in daylight to keep that night from swallowing the house. Policy in the room. Paychecks on the line. A working class still visible. If you think you’re lonely now, here’s how people fought not to be.

Two pages talk to each other: Bobby’s bedroom monologue and Jet’s birth-control ad.

The ad is 1982, speaking in women’s voices about a cheap, discreet, mail-order spermicide. No doctor visit. No applicator. Shows up in an unmarked envelope. That is control you can hold in your hand. It normalizes Black women setting terms for sex, timing, and family planning in the middle of a tight economy.

Now hear the song again. His lines are a working man’s ledger and a control check. “She’s always complainin’…” “Her girlfriend’s got…” “I can’t be in two places at one time.” He is stretched by shrinking hours and rising costs, and he is rattled by her new leverage. If she can choose when to have sex and when to have kids, she can also choose when to leave. So he tries to flip the power with a threat dressed as a warning: “If you think you’re lonely now… wait until tonight. I’ll be long gone.”

That is the backlash note. Not cartoon villainy. A bruised provider identity colliding with female autonomy and consumer aspiration. The ad tells her, you don’t have to plan your life around his paycheck or a clinic’s hours. The song tells her, don’t push me, I can withdraw what I still control. Night becomes the arena where these forces meet: contraception makes desire speak louder; austerity makes his pride speak louder. “Needs come out to breathe” hits different when birth control makes those needs negotiable on her terms.

So it makes sense. The magazine sells agency in the margins of a shrinking wage world. The record captures the friction that follows. One page says, “your body, your call.” The other answers, “my hours, my house.” The hook is the stalemate. The way out is naming both truths and building a life where the power isn’t all in the paycheck or all in the bedroom.

Jet is showing you the whole renegotiation of the house, not just the headline shock.

First, the Semicid page said plain: Black women are setting terms on sex and timing. Cheap, discreet control you can order by mail. Because autonomy got practical in ’82. Now flip to “The Sexes.” The wild murder-for-hire story is tabloidy, but its job is cultural policing. It screams, “female desire out of bounds,” so the audience gets a cautionary tale. Because when women gain leverage, the first response is often panic stories about what happens when they use it “too far.”

Second, the Massachusetts item shows the state drawing bright lines around family structure. Who can marry whom becomes a proxy fight over authority in the home. Because when private power shifts, public rules tighten to hold the frame.

Third, Georgia’s prenup ruling is the quiet revolution. Courts admit marriage is also a contract in a high-divorce era, so talk assets upfront. Because the provider model is wobbling, wages are thinner, and property gets negotiated the way shifts used to be. Love and logistics share a table now.

Put that against Womack. Her agency rises, the law codifies new rules, the tabloids moralize, and the working man’s identity feels cornered. So he reaches for the power he still has: presence and withdrawal. “If you think you’re lonely now… wait until tonight” reads like a breakup but functions like a boundary in a world where the old boundaries moved.

That’s why these pages sit together. Birth control ad. Sex panic blurb. Marriage law update. They map the same fight Bobby sang: who sets the terms in the house when the job can’t.

Class mobility in a movie poster.

“Toughest drill instructor made him an officer. A woman made him a man.” That’s 1982 handing you the script. When the plant starts thinning, the Navy becomes a ladder. Rank stands in for the paycheck that used to come from the line. Louis Gossett Jr. plays authority you can earn from, not just survive. That matters next to the Weinberger pages where the Pentagon courts Black media and talks promotion pipelines. The uniform is a jobs program and a status fix.

Now fold in the house. Debra Winger’s factory worker isn’t a muse. She has terms. The tagline says it plain: manhood is negotiated in intimacy, not just forged on the drill yard. That rhymes with the Semicid ad and the prenup ruling. Women setting the clock. Contracts named out loud. The bedroom becomes the place where promotion meets commitment.

Put it against Womack. He’s the working man saying, I’m stretched and I still want control. “Wait until tonight” is his leverage. The poster answers with the counter-myth: become more than a worker and meet a woman who won’t let you be less than a man. Two routes out of the squeeze sit side by side in this issue: Miller after the shift, or the military as the new shift. Either way, night is where the truth shows up. The drill yard trains the body. The house decides who you are.

A chorus of the era on one page.

Isabel Sanford cracks the TV joke that lands like policy: you watch shows that teach you to lose the weight you wouldn’t have gained if you weren’t watching TV. That’s the same lullaby as Miller Time. Sedate the ache after work and call it self-care. Then Dr. Vernard Johnson offers the counter. Church as the “high” that doesn’t crash. That’s Bobby’s register: testify the wound, sing the coping.

Terry Cummings warns about living by statues and star players. Translation: envy is a schedule. “Her girlfriend’s got…” wasn’t just a line in the song; it was a whole economy of aspiration aimed at houses with shrinking shifts. Senator Tsongas swings in with the cold quip. Reagan signing the Voting Rights Act is “Bonnie and Clyde coming out for gun control.” Cynicism, but it marks the pivot: rights framed as PR while austerity tightens.

Rita Marley closes the loop with autonomy over promoters, calling over commerce. That’s the women’s throughline from the Semicid ad to prenups: set your terms and don’t apologize. Put it all together and you hear why Womack hit so hard. The decade offered two paths through the night: buy a remedy, or build a ritual. Celebrity told you who to be; church told you how to stand; politics told you to wait. Bobby named the hour when all of that walks into the same room and asks, “Who are you holding?”

Baldwin in the birthdays box feels right. A quiet square of a man who taught me how to hear a hard truth without flinching. He called Harlem an occupied place. He said the badge, white or Black, often showed up as the state’s blunt instrument. He wrote that some Black officers in Black neighborhoods could be the hardest on us because they had something to prove. I wore the badge. I can’t duck what he saw. I have stood in living rooms at 2 a.m. where a policy failure got handed to a patrol car and told to fix it.

That’s why he is still my hero. Not because he was gentle to my profession, but because he refused to lie about its job in a starving system. Baldwin named the structure. Womack scored the feeling. The plant shrank, the safety net thinned, and the house carried the weight. One page says “become an officer.” Another page says “be a gentleman.” Baldwin asks the only question that matters at night: who are you serving, and who pays the bill for that service.

What I take from him is a charge, not a wound. Tell it plain. Don’t hide behind the uniform or the microphone. Build a world where the badge isn’t asked to replace jobs, housing, and care. Until then, I will honor the man who told the truth about us and still loved us enough to keep writing.

The greats still clock in.

Fringe flying, mic up, a fan onstage singing from the gut. That’s not nostalgia. That’s proof. The room is a union hall with lights. Call and response is the contract. Sweat is the receipt. Right before the Womack spread, this page says what he’s about to testify: the job might shrink, but the work is still sacred. You show up, you shake the floor, you carry folks through the night.

Here are the receipts the issue gives you, then the read.

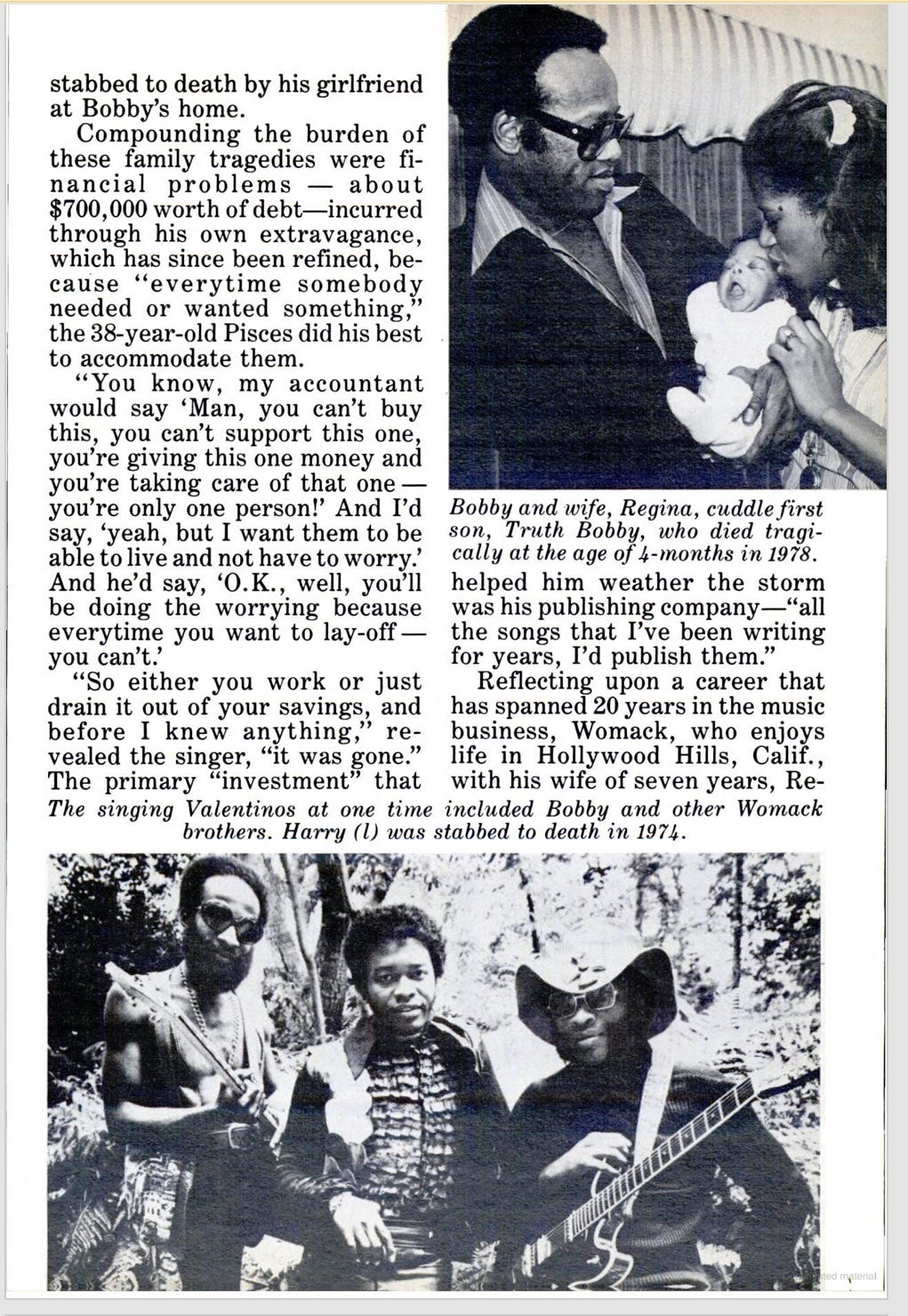

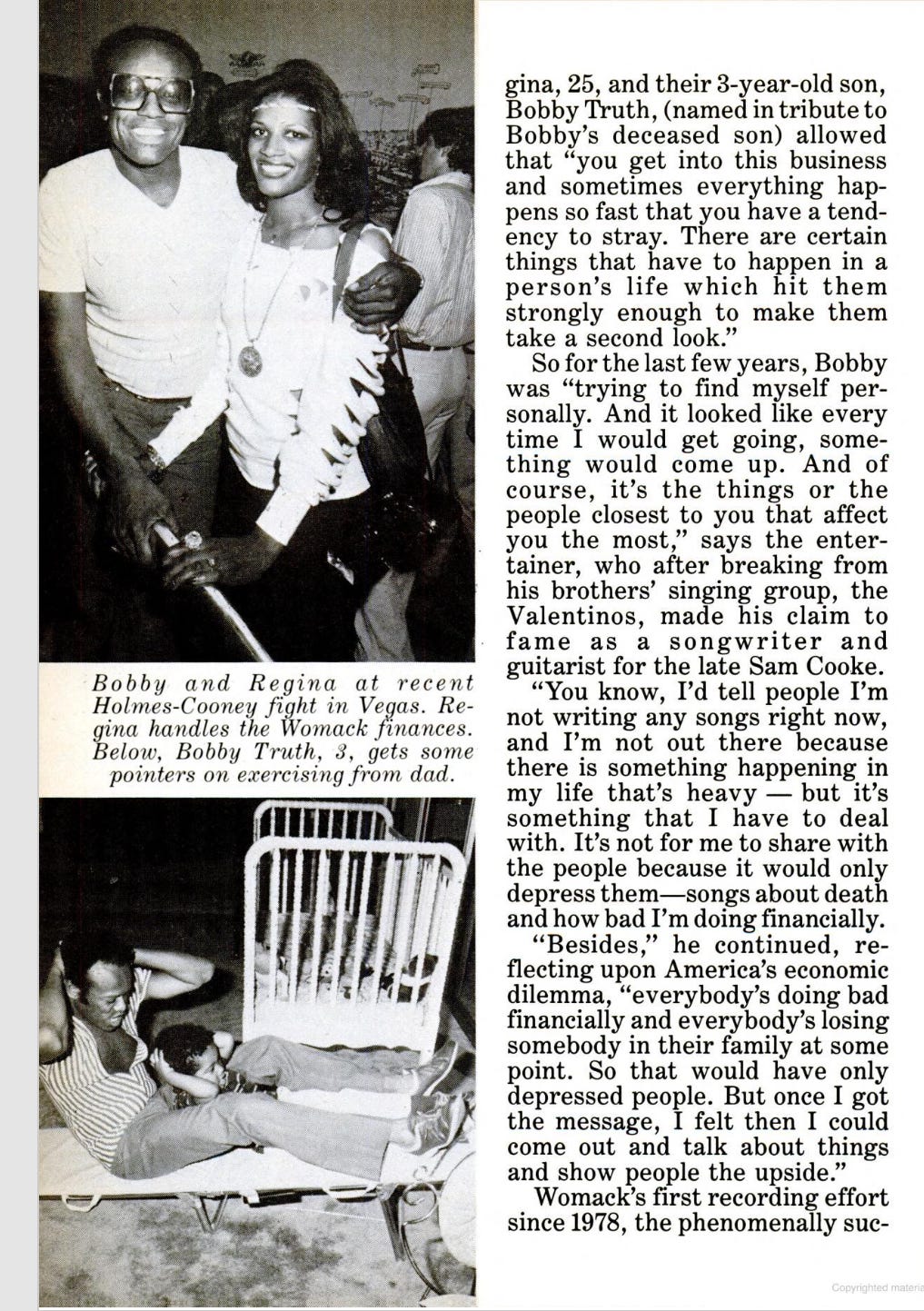

Womack’s comeback is real. The Poet hits. “If You Think You’re Lonely Now” carries it. Debts paid. He says it plain: I can make the money, I can’t manage it. Regina runs the books. That’s a Black household truth at star scale. The man performs. The woman keeps the house from falling. It lands because half your aunties did the same job with a ledger and a purse.

Then the weight. A four-year pause. Father gone. Brother murdered. Infant son lost. About $700,000 gone to generosity and excess, then the accountant’s cold math: either work or drain your savings. He chooses work, and the publishing catalog becomes the lifeline. That is blue-collar logic in an entertainer’s suit. When the plant shrinks, you lean on what you already built.

He wants the Sam Cooke role. He grills in the yard. He writes at a crowded desk. He wrestles with the same temptations the ad pages push at you, and the same fixes the church pages preach to you. This is the same magazine that sells Miller Time, birth control by mail, and a court saying prenups are just contracts now. Jet is showing the new house rules while Bobby is living them in public.

Now hear the song again. The chorus is not just a threat. It is a night audit. Hours thin. Pride takes hits. Bills breathe louder. She has new leverage. He reaches for the power he still owns, which is presence and withdrawal. “Wait until tonight” is how a man in chaos tries to draw a line. It sounds like romance. It feels like a policy failure landing in a bedroom.

Why this matters to you right now. Back then you could still “put in the work,” even as overtime vanished. Today the app is the foreman and the night never ends. The feeling is the same. What saves the house is the same. Truth told in church cadence. A partner who can stretch a dollar. A catalog of work you can lean on. And a community that insists on trade, not aid, so the money you pour in comes back through your people.

So read Womack as witness, not gossip. He is the poet of the night shift. He names what the day took and what the house must carry. If you think you’re lonely now, remember what he showed on these pages: sing the wound, count the money, hand the books to someone you trust, and keep clocking in.

Trump and Lutnick Targeting the 43 Trillion dollar Pension Fund for Their Crypto Ventures and it should be criminal !!!!

This file show the Total 43 Trillion dollar Pension fund file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Release%20Quarterly%20Retirement%20Market%20Data%20First%20Quarter%202025.pdf