It Don’t Hurt Now (Until It Does)

Flying a Broken Country Toward the Truth

Picture a tired 767 that has already run out of fuel, gliding over black water at three in the morning.

Today’s essay is that plane.

I’m wrestling with demons tonight.

The captain is you or me, whoever is still awake enough to hear the feedback howl from the cockpit speakers, and there are only two choices.

Drop the nose, put the fuselage into the ocean now, and pray the rescue crews find us before the waves and whatever is hunting beneath them drag metal and bone into the cold dark.

Or talk ourselves into believing this ninety-five-ton bird is a paper glider that will somehow, some way, float toward a thin strip of island runway in the middle of nowhere, far too short for a jet this size, while every soul on board can see the cabin lights have gone dark and can hear the engines have gone silent.

On a normal night I would already have a clean title, a tidy outline, and a call to action that knows how to land as smooth as Air Force One kissing the runway at Andrews Air Force Base before I ever wrote a single word, but tonight even that flight plan is gone and we are flying by ear in full Jimi Hendrix fashion.

How Grown Folks Survive

Somewhere along the way, I realized this isn’t a “me being sloppy” story so much as a “how grown folks survive” story. Even the best professionals end up here: something goes wrong in the maintenance hangar, a slow leak starts, and the instruments begin to whisper that the fuel is lower than it should be. The danger doesn’t just come from the leak; it comes when we look at those gauges and decide not to believe them, because believing them would mean changing everything. So we do what experts in every field do: tighten our jaw, call it turbulence, and tell ourselves it don’t hurt now.

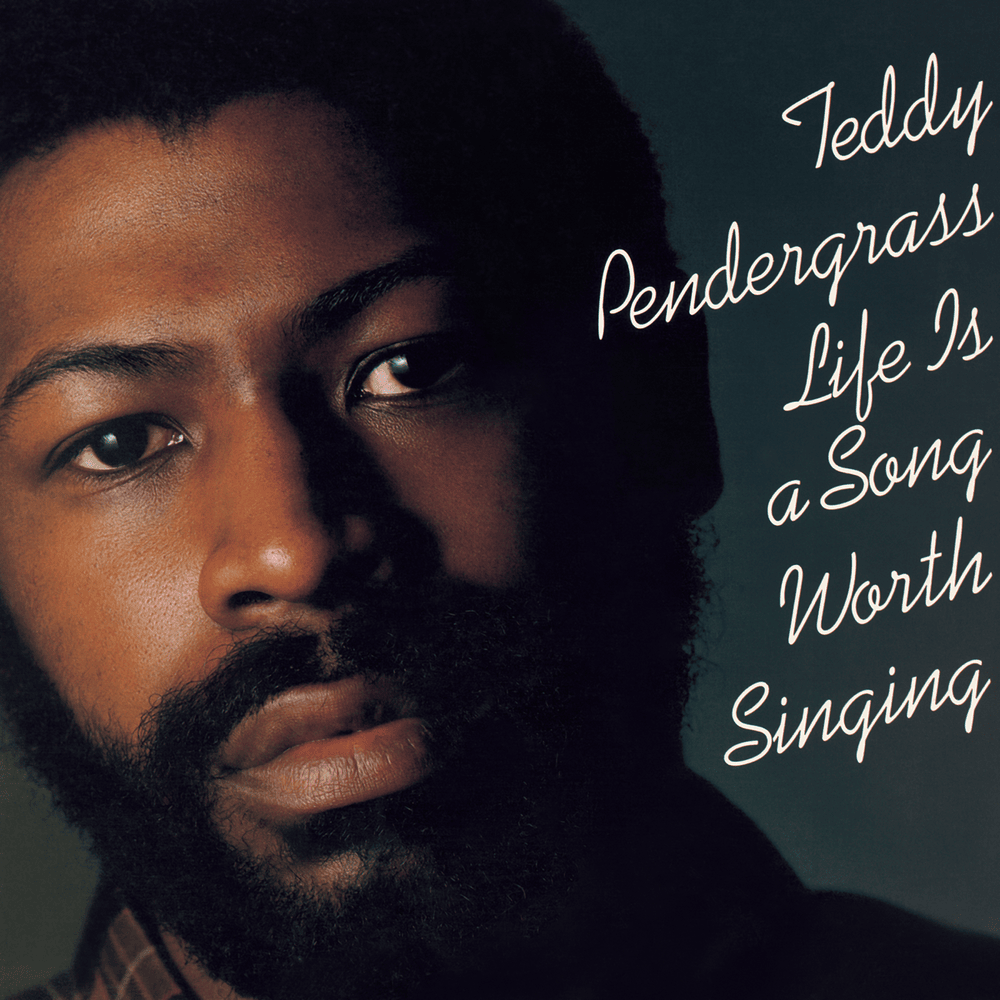

That’s how I slid from a little Substack with a handful of readers into a platform with daily series and real expectations without quite noticing the weight. The growth has been a gift; it’s also meant stacking a weekday briefing here, a media breakdown there, and promising that something thoughtful will be waiting for you Sunday morning. This piece was supposed to be one of those Sunday drops. I used to write when the spirit grabbed me by the collar and refused to let go. Now I write on a clock, even when the collar stays loose and the only thing grabbing me is the calendar notification. Saturday night I was sitting in the dark, cursor blinking, playlist on in the background, waiting for inspiration that did not show up on schedule, and when Teddy Pendergrass drifted in singing “It don’t hurt now,” I heard myself in that hook more than I heard him: the working lie that says you can keep going, that you’re fine, that it don’t hurt now.

What I’m slowly admitting is that writing professionally isn’t about being lit up all the time; it’s about learning how to function while a part of you is already tired and sore, and still telling yourself just enough of a lie to keep moving. We all do it when we put on the uniform, the work badge, the “I’m fine” smile, and step into a world that’s gone sideways instead of staying home and collapsing. There’s a reason one particular flight that ran out of fuel over the Atlantic keeps living in my head: not because the crew were amateurs, but because a small mistake in the hangar met that very human capacity to look at the warning lights and push on anyway. That’s the move I recognize in myself, and maybe in you in the way we steady our hands on the controls, feel the cabin lights dim, and still tell ourselves, with a straight face, that it don’t hurt now.

Fuel Leak

On August 24, 2001, Air Transat Flight 236 left Toronto for Lisbon just like any other red-eye: 293 passengers, 13 crew, a nearly new Airbus A330, and a captain with tens of thousands of hours in the air. This was not a rookie outfit. They even had extra fuel on board, about five tons over the legal minimum, enough on paper to cross the Atlantic with room to spare.

The trouble started days earlier in a maintenance hangar. Mechanics swapped out a Rolls-Royce engine and, because of a mismatch in configurations, re-routed a fuel tube and a hydraulic line so they sat closer together than they should have. On the ground the fix passed inspection and a test run; in the air, the two lines rubbed against each other until the fuel line wore through. Suddenly the plane was dumping 12 to 15 tons of fuel an hour through an invisible wound, while each engine normally burned only about 2.6 tons. The leak was massive, but the engines kept humming and the passengers kept watching movies.

Mid-ocean, the first clues showed up not as “FUEL LEAK” in bright letters, but as weird oil readings and a fuel imbalance between the left and right wings. The pilots did what trained professionals do under pressure: they checked the manuals, called maintenance on the ground, compared notes, and tried to fit the data into a pattern they recognized. They convinced themselves they were looking at a computer glitch instead of a hemorrhage, and when they opened a crossfeed valve to “fix” the imbalance, they unknowingly sent even more fuel through the damaged side. It was classic framing bias: once they decided it was a sensor problem, every new detail was bent to support that story, and the possibility of a leak stayed in the blind spot.

By the time the numbers finally forced them to divert to a tiny runway on a Portuguese island, the tank was almost dry. One engine flamed out, then the other, the cockpit went dark, oxygen masks dropped, and a 200-ton jet became the world’s heaviest glider. With only a wind-driven emergency turbine feeding just enough electricity to keep a few instruments alive, the captain and first officer had to glide more than 100 kilometers, bleed off altitude with a circling turn, and slam the plane onto the runway at about 200 knots, bursting eight of twelve tires. They stopped with about 600 feet of concrete left. Everyone walked off alive, and the crew later got airmanship awards for pulling off the longest engine-out glide of a passenger jet in history.

When investigators dug in, they found the three-part pattern beneath the miracle: a small but crucial maintenance error, training that had never really walked crews through a fuel-leak scenario like this, and a very human tendency to cling to the least painful explanation even as the gauges scream. That combination is what stays with me. A hidden wound, a system that never taught you how to name it, and a practiced voice in your head that keeps insisting you can still make it, that you are fine, that it don’t hurt now.

A Line Run Wrong

America built its version of capitalism like that Airbus in the hangar: on paper everything gleamed, the instruments were set to “all men are created equal,” and underneath there was a line run wrong on purpose. The whole system depended on treating Black flesh as fuel and profit, right down to the way rape of enslaved women produced “valuable property and future laborers” for white families and pumped wealth and status into institutions that still run the country today. Systemic racism theory is just the modern phrase for that rigged panel: slavery’s violence baked into law, church, medicine, and money, then passed forward as inheritance so that the leak becomes invisible, the damage normalized. The national story had to say: this is freedom, this is virtue, this is the city on a hill. Translation: it don’t hurt now.

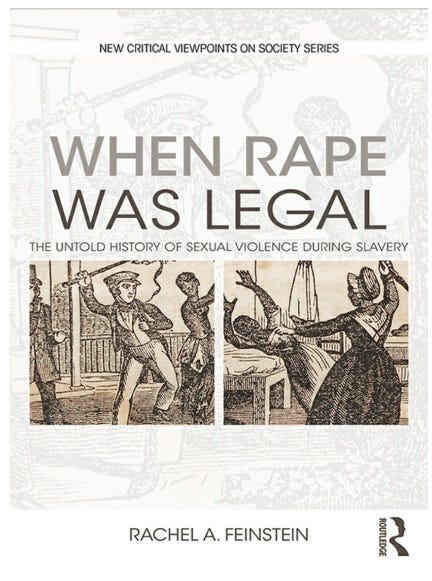

The examples in this section—the “young master” in Georgia, the Maryland girl with the knife, the mothers buying light-skinned girls for their sons all come directly from When Rape Was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery. I’m drawing on the author’s concept of a “counter frame” to describe how Black women and their families named and resisted a system that insisted their pain didn’t count.

On the ground, enslaved Black women and girls knew exactly how much it hurt. Sexual violence wasn’t a scandal; it was “a social norm,” a standard way white men exercised power, bonded with each other, and taught their sons what white manhood meant. Refusing a white man’s advances could mean whipping, being sold away, or slow death by “hard usage,” so the terror didn’t always show up as dramatic resistance; sometimes it lived in the quiet knowledge that saying no might cost you your life. Meanwhile physicians and preachers called sex a health need for white men and a moral failing for Black women, turning exploitation into medicine for one group and damnation for the other. When the whole culture says your body is a recreational perk, a “play thing” to “amuse” a white boy at the fireside, what language do you even have left for your own pain? You learn to function inside the contradiction. You keep breathing inside a world that calls your wound normal. You learn to say, just to get through the night, it don’t hurt now.

But the record is full of people who refused to let that framing be the last word. A mother tells her light-skinned daughter, summoned by the master at sixteen, to “hold up her head above such things, if she could,” planting a different story in the girl’s mind even as the system punishes her for it. An anonymous woman in Georgia fights back against the “young marster,” gets whipped naked in front of a crowd, and still tells her abusers that in stripping her they have stripped their own mothers and sisters, asserting that “God had made us all, and he made us just alike.” A girl in Maryland grabs a knife, ends the life of the trader who tried to “satisfy his bestial nature,” and survives because someone in power finally sees enough of her humanity to protect her. Fathers, brothers, and the husbands like Clarke and Macks mentioned in Feinstien’s book bear witness to “hard battles” Black women fight to protect themselves, refusing to describe them as passive victims even when they lose. Underneath the imposed script where the words hypersexual, property, plaything stand out there’s a counter-frame being whispered: I am not what you say I am. You can’t name me. That whisper is the ancestor of every time we square our shoulders in a hostile room and tell ourselves it don’t hurt now.

And don’t forget: enslaved Black people had front-row seats to the performance of white virtue. They saw the plantation version of “courting,” the special rooms, the gifts, the jewelry, the quadroon mistresses set up in cottages “for the exclusive use” of some young master, carefully staged so white men could see themselves as gentlemen while committing what Jacobs called “the most deplorable acts.” They watched mothers buy light-skinned girls for their sons “to make Charley steady,” churches preach purity while sons bought raped girls at auction, doctors prescribe sex with Black women instead of facing their sons’ inner turmoil. So when I see Congress today patting itself on the back for yanking twenty thousand pages of emails and records out of the Epstein estate, including messages where he bragged that a certain sitting president “knew about the girls,” I hear that same old plantation logic trying on the costume of transparency. We get bipartisan votes, 427 to 1 in the House and unanimous consent in the Senate, to pass an Epstein Files Transparency Act and speeches about justice for survivors, after years of delay, denial, and quiet benefit from the very system that made Epstein possible. The stagecraft has updated, but the script is familiar: clean the ledgers in public, keep the deeper structure of who gets protected and who gets believed humming in the background, and reassure the country that by releasing files we have proved it don’t hurt now.

All that past hypocrisy, terror, and stolen intimacy was swirling together for so long until it had to come out somewhere, in field hollers, in work songs, in spirituals that said one thing to the master and something entirely different to the people humming under their breath. Over time that double speech bends into the blues, then R&B and Soul, then a man named Teddy Pendergrass can stand in a studio generations later and sing “It don’t hurt now” with a voice that knows damn well it does.

So when I hear that line on a late-night playlist, staring at a blank screen, I’m not just hearing one man trying to get over a breakup. I’m hearing a centuries-old survival algorithm, reframe the wound so you can keep moving. Our great-grandmothers did it walking back from the whipping post, our grandfathers did it watching bosses paw at Black women they loved but could not protect, our parents did it at jobs where they swallowed rage to keep the lights on. We still do it when we laugh off the microaggression, minimize the diagnosis, shrug at the news that yet another powerful man’s “secret files” are coming out and tell ourselves we’ve already seen the worst. We still do it when we watch another video of a Black body brutalized on screen and say, “I’m tired, but I’m fine.” This is how a people trapped inside someone else’s cockpit have stayed alive long enough to tell the truth about the leak: by singing, by joking, by showing up anyway, and by repeating, sometimes in a whisper and sometimes in a shout, the little lie that kept us from going under. It don’t hurt now.

THEY Got To Her

Last week I wrote about Marjorie Taylor Greene’s resignation like a newsroom pro, straight headline, clean lede, quotes from both sides, no fingerprints. Tonight I’m going to tell you what I actually saw. In a that seven-minute video of an interview on CNN which foreshadowed her resignation, this woman who built a brand on shouting looked like a hostage reading terms of surrender. The eyes weren’t lit with grievance; they were scanning an invisible teleprompter only she could see, trying to stitch together dignity, fear, and defiance after Trump called her a traitor, sicced his people on her, and made it clear she was expendable. For five years she rode the dragon of white grievance politics; on the week of November 21, 2025, we watched it turn and swallow her whole.

Look at the arc. She came in on QAnon fumes and “America First” slogans, cheering family separation, mocking survivors, running defense for a man whose power rested on the same old hierarchies this country has always protected. Then, for reasons that may be part conscience and part calculation, she starts pushing the Epstein Files Transparency Act, stands in front of cameras and says the victims deserve the truth, and openly questions why Trump is leaning on Congress not to release the names. In the old plantation script, that’s the moment when the favored overseer starts wondering out loud why the master keeps buying girls. You can’t play both roles forever. You can’t be the face of a movement built on cruelty and also claim you are standing in pure solidarity with the people that cruelty crushes. Truth and hate are incompatible; eventually one has to go.

White supremacy always sells itself to white people as a way to avoid pain: your losses are someone else’s fault, your fear is righteous, the harm you inflict isn’t really harm because the people on the other end aren’t quite as human as you. It whispers: this is strength, this is order, it don’t hurt now. So Greene could stand onstage for years, amplify lies that put targets on Black backs, on queer backs, on immigrant backs, and tell herself she was “protecting America.” Then the same machine she fed turns on her, and suddenly she is the one talking about being a “battered wife” in politics, the one saying the threats are too much, the one walking away to preserve what’s left of her life. In that resignation tape she doesn’t look like a warrior; she looks like that character in a movie who thought she could flirt with the dark side and keep her soul, then realizes too late that they own her now.

That’s the difference I’m trying to name. Black folk have had to tell ourselves “it don’t hurt now” just to hold our pieces together, to get through the day without shattering under what was done to us. White supremacy uses the same sentence in reverse: to numb its own conscience so it can keep doing the harm. One is a bandage on a wound you didn’t choose; the other is a blindfold you tie over your own eyes so you don’t have to see what you’re doing. Greene’s resignation doesn’t mean the system that made her is gone, no, not even close. But it is a flare in the night sky, a reminder that every person who walks down that path eventually runs out of fuel. Sooner or later you end up alone at a mic, justifying the wreckage, realizing the lie you told yourself to keep hurting others has circled back on you, and the only thing left to say, if you’re honest, is that it does hurt now.

My Promise Tou, My Promise To America.

I’m not writing this like a man waiting on a fickle muse anymore. I’ve seen what happens when you trust the feeling more than the gauges. Flight 236 made it to that little island because, once they finally accepted the truth about the leak, they flew the plane they actually had, not the one they wished they were in. That’s the promise I’m making here: XVOA is not going into the Atlantic. I’m going to keep showing up at this keyboard on every damn day, even when it stings, and steer this thing toward a runway you can walk away from.

I’m also not going to turn “it don’t hurt now” into a license for my own cruelty. I have watched what happens when Black pain curdles into contempt for Black people, when somebody like Justice Clarence Thomas or Candace Owens cashes in their wound by siding with the very forces that created it. I am not using this platform to become an overseer with better vocabulary. When I think about the girls and young women whose names live in those Epstein files, shuttled around on private jets while powerful men told themselves their pleasure didn’t really hurt anyone, I know exactly what kind of lie I refuse to tell. The mantra for me is not “it don’t hurt now, so I owe you nothing.” It is “it don’t hurt now quite as much, so I have enough breath left to love my people, tell the truth, and refuse to dehumanize even the ones who see me as their enemy.”

And as twisted as our history is, I still believe there are enough of us in this country to turn the plane. The same slaveholder who wrote “all men are created equal” also sat down later and admitted, however dimly, that slavery was a moral time bomb that would bring judgment on his country and on his own children’s children. He never made anything close to full amends; hundreds of people he owned died in bondage, and his contradictions are not only carved in stone but the contradiction in his words help to inspire a whole new genre of American music.

Now if a man that compromised could at least tremble at the cost of what he’d helped build, then a nation that knows better has no excuse. We can name the leak, fix the lines, and finally stop pretending that centuries of damage from plantations to private islands can be wished away with a slogan. The work ahead will hurt, and we should say so out loud, but that is exactly why we have to do it.

So I’m planting my flag right here, with this busted little essay that almost didn’t get written: I’m not crashing this story, I’m not surrendering to cynicism, and I’m not surrendering you to it either. I choose to believe that we can look at what we’ve done, to each other and to ourselves, and still decide to land this thing together. And if we need a flawed prophet from the founding era to remind us what time it is, he already left us the line:

“Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever.”

Right now, there are 82 of you who have already climbed on board as paid subscribers, and I don’t have words big enough for what it means that you’ve carried this little plane this far. The Bestseller checkmark at 100 isn’t a vanity trophy; it’s the algorithmic megaphone that decides whether essays like this stay in a quiet corner or get thrown into the wider sky where more people wrestling with “all men are created equal” can actually find us. If you’ve been riding along for free and felt something in your chest while you read this, I’m asking you to help me close the last 18 yards and become one of the 18 more souls we need in this cabin by upgrading to paid here:

I’m committed to flying this thing toward a country that finally starts to live the words it wrote, and if you believe that work matters, I’d be honored to have you sitting up front with me.

Xplisset, thank you for this moving and excellent piece of writing. I am a white woman. One of my closest friends is a black woman I work with. Because of my friendship with her, I spent a lot of time reading about slavery and how the slaves were treated pre-Civil War (and probably afterward). I was raised in the South, part of the Baby Boomer generation. I've heard terrible things come out of people's mouths. I remember the separate bathrooms and water fountains. That, of course, was not the worst of atrocities. The Klan walking up and down streets was terrifying. I was rebellious enough to ask why. No satisfactory answer. These things need to be kept in front of people always, especially with the sick regime in the White House.

This was far from a "busted little essay." I was first attracted to this Substack by the quality of the writing. I subscribed because it helped me to look at familiar things from a different perspective. A piece like this, which demonstrates both, makes me happy I became a paid subscriber. You deserve to get a lot more than the 18 paid subscribers you need to break 100.

Like many others, I suspect, I viewed the Epstein sex-trafficking ring as A Bad Thing, A Moral Failure, and Another Example of How the Powerful Exploit the Less Powerful. I never thought to compare it with the kinds of abhorrent practices associated with the institution of slavery as you so graphically describe it in this essay. And the subtitle of the essay is superb.

It was in college that I first learned to think about some of the imperfections of our country that I had been seeing while growing up, and how it might be possible to work to make her better -- to be all that we could be, to live up to the promises of our founding documents. But I don't think of her as broken. At least not yet. She's far from perfect, with some parts jury-rigged together as she flies. We've been making changes to keep her going for the benefit of her passengers. But she's now been taken over by group of terrorist zealots who are trying to dismantle her. Maybe break her up so they can sell off the parts for profit. Or squeeze everything out of her before they jump ship. Maybe it's time for the passengers to rush the cabin, like the desperate heroes of Flight 93, but this time to stick the landing, like the crew of Flight 236.