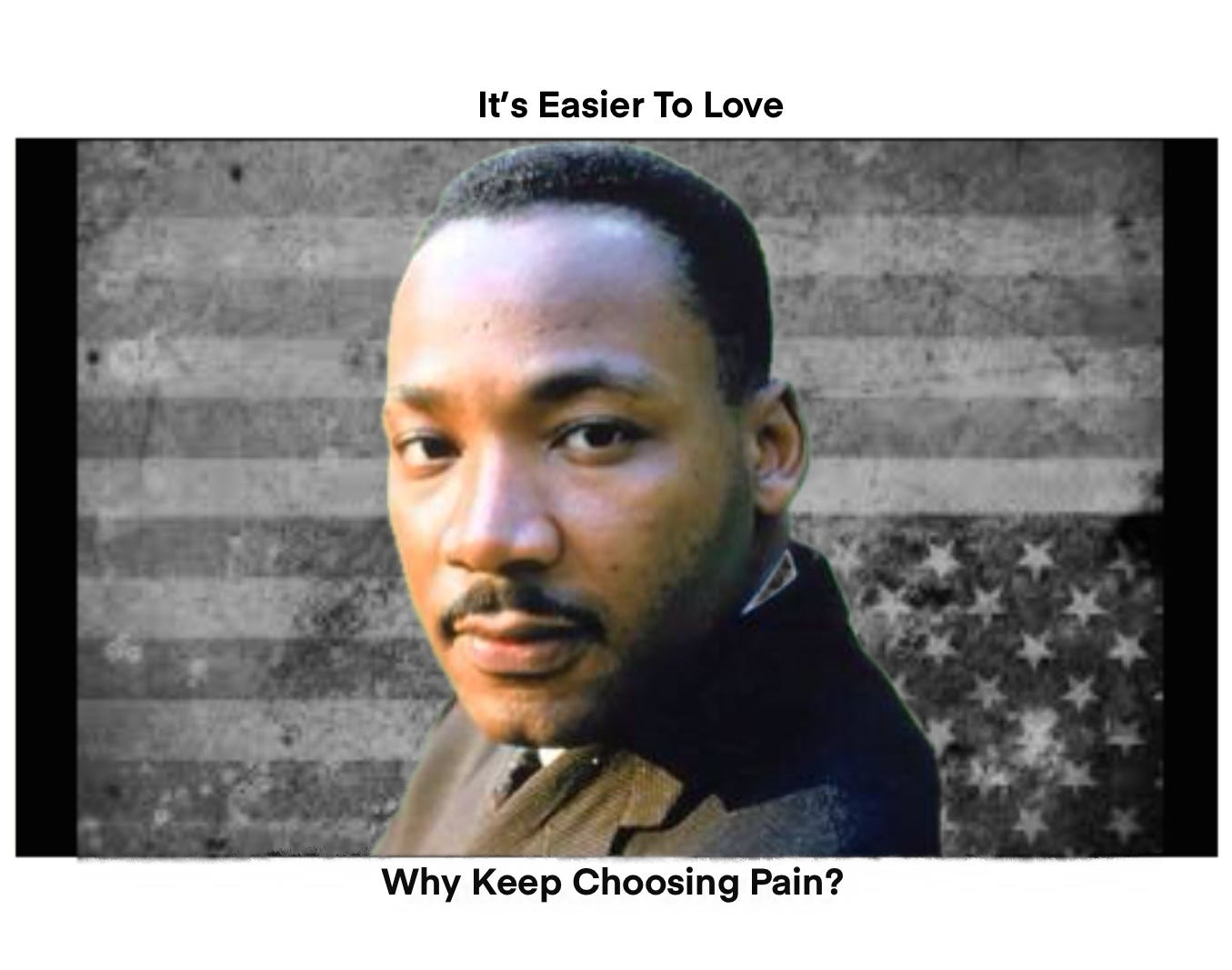

IT’S EASIER TO LOVE

Why keep choosing pain?

With Dr. King’s lesson that love is a discipline in my ear, I didn’t want to write this. It sounds weak. Maybe it is. You’ve heard me say this before. Write that which you don’t want to write. I remained silent on what happened in Utah. I told myself I was waiting for facts. Truth is, I was afraid of my own empathy.

A man is dead. A stage is stained. Somewhere a wife opens a door she never wanted to open. Somewhere a child learns a new word for forever. Here is the knot: I feel a human pull toward him. I use love with gloves on, but I mean it plain. If I could put time back in the chamber and stop that bullet for his family, I would. In a heartbeat. And still, the other truth stands. His ideas helped salt the ground we walk. They hardened small doors against people who look like me, look like you, love who you love. I won’t pretend otherwise.

“Won’t someone please explain, why all the hurt and the pain?” — Sister Sledge

If y’all don’t mind, I want to take you back to the summer of 1979. Windows down. AC off or no option for ac whatsoever because it was still a luxury and the radio needed room to breathe.

“We are family.”

“I got all my sisters with me.”

The hook lived in 8-tracks and cassette decks and came right back on FM when the tape sagged and you “ejected” out to give it a rest. On the block you heard,

“get up, everybody, sing.”

On sidewalks it felt true that

“everyone can see we’re together as we walk on by.”

Friends shouted “birds of a feather” and meant it. For one long summer a chorus made strangers a we.

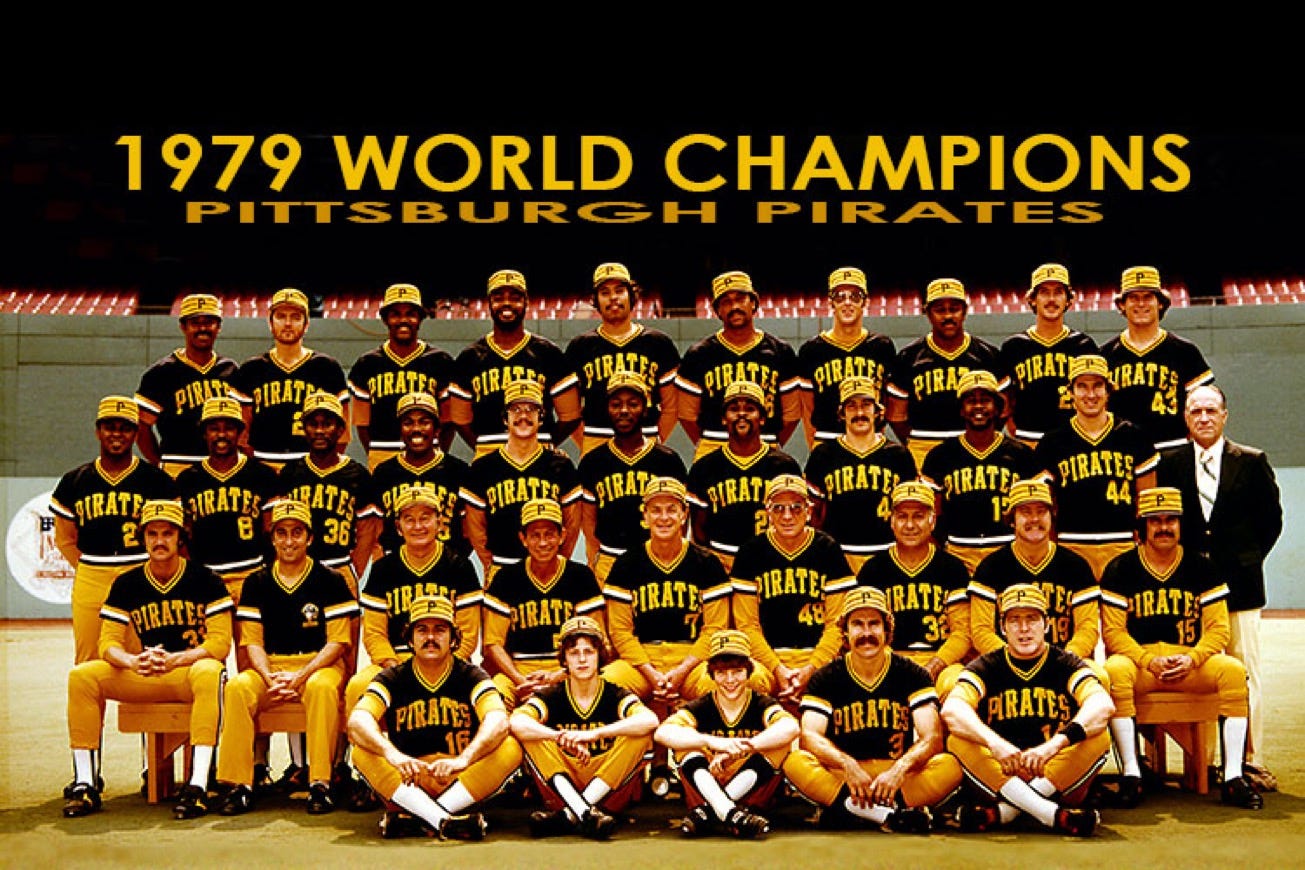

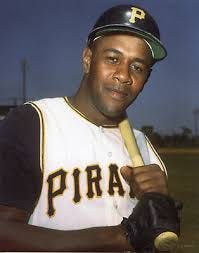

Inside the Pittsburgh Pirates clubhouse that same summer, the season had started rough. Then one night at Three Rivers Stadium the PA blasted “We Are Family.”

Willie Stargell asked the bench if they liked it and said, “That’s our song.” Some players had pushed for “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now,” a pure victory chant. The captain chose belonging over bravado. The room followed. Morale tightened. By August the Pirates were in first. The chorus jumped from dugout to city, and by October they finished the job and won the 1979 World Series. In the park and on the block the promise felt real enough to “state for the record.” What we were giving was “love in a family dose.”

That “we”was not abstract in the house I grew up in. My father got a leg up through a city training program that led to a union job with a wage you could build a life on. My mother used the GI Bill, even though that door had a history of opening for some and not others. Yeah, my momma wore combat boots. Those ladders put us in a middle-class lane and put me in private school. The kitchen table tracked the lyric in plain English.

“Living life is fun.”

“And we’ve just begun to get our share of the world’s delights.”

“high hopes for the future.”

“And our goal’s in sight.”

If you’re wondering how a cop who filed dry reports writes like this, that’s the answer. Policy ladders built these sentences. Training to a union card for my father. GI Bill to college tuition at Howard for mother. That gave money later on for tuition to a hallway where I was the only Black kid most days, carrying a Latin textbook with my name written inside and learning Western Civ next to kids who had never met my block. I was pondering the fall of Rome in 7th grade.

In 1979 the screen was teaching me the terms while the radio taught me the chorus. Some of you were right there with me no not literally but in a sort of shared cultural experience missing these days. Ya’ll remember. That was the year Benson arrived, a Black man running a house that wasn’t built for him.

That same year The Facts of Life debuted and turned a mostly white private school into a lesson on belonging, and we saw my own hallway in Tootie’s smile. Diff’rent Strokes was already a hit by then, selling the adoption dream and the price of the house rules.

The Jeffersons was still moving on up, giving working-class Black pride a theme song for hustle and friction. These shows gave us the “golden rule” in practice.

Caption: James Law with his mother, Faye, and father, Edgar, in the backyard of their Granada Hills home. From the 1982 article Black middle class: Getting used to isolation in the LA Times.

“Have faith in you and the things you do.”

If you do the work,

“you won’t go wrong.”

That was our “family jewel.”

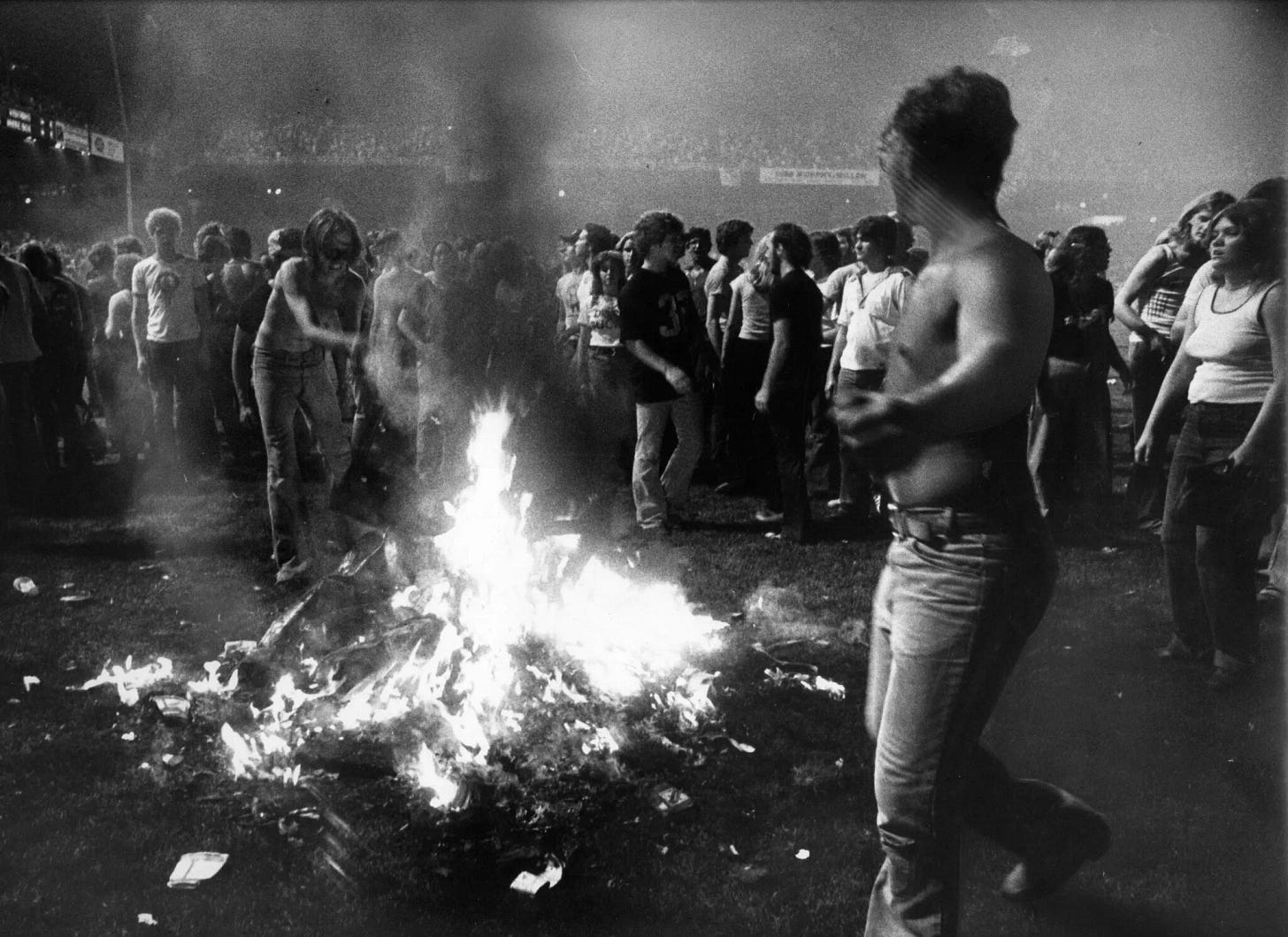

For a season it felt unstoppable. I can hear people saying, “we didn’t get depressed,” and the laugh that follows because the music made it feel true. But even that summer not everyone was singing.

Some folks were busy burning the music and calling it a joke. That crack in the surface matters, because a family isn’t only a chant. It is how we act when the heat rises and power shows its teeth.

Flip the 45.

Sometimes it seems that way to me.

It’s easier to love, don’t you see.

Bernard Edwards and Nile Rodgers lived inside the late-’70s split screen. Nightclubs where the room was mixed, the groove was democratic, the bassline told you your body belonged. Then you step outside into a country still fighting over where children can sit. If you toured America in 1979 you did not have to squint to see the heat under the disco lights.

You could dance to “We Are Family” and walk past a TV in a diner replaying school buses with police escorts.

Won’t someone please explain, why all the hurt and the pain?

Can’t you make ’em see, it’s not supposed to be?

Look at the first picture above. A flag becomes a spear in a city block. That is not a metaphor. That is anti-busing rage in broad daylight, aimed at a Black body for daring to move through public space. This is the undertow the A-side could not carry.

Bernard Edward’s and Nile Rodger knew audiences who felt safe in the club would ride the same subway home through neighborhoods tense with court-ordered integration. Musicians of their generation were raised in the long shadow of the movement. You learn fast that love is policy as much as feeling. The lyric lands like common sense dressed as a plea: if it is truly easier to love, why do we keep choosing spectacle and pain.

Sometimes it seems that way to me.

It’s easier to love, don’t you see.

Now this picture. Same award-winning eye who took the flag as spear, Stanley Forman. It’s a mother and a child falling from a fire escape that she trusted to hold. The child survives. The mother does not. That is what “benign neglect” looks like when it reaches the body. Housing codes unenforced. Blocks starved of investment. Ambulances late. People making do. In those same years the country argued over buses while whole buildings leaned into failure. The chorus says “please let the children play.” The street says the playground is a fire escape.

What more can I say? War is no game you play.

Give a person a little might—

well, that don’t make him right.

Busing fights crowned winners and losers on the evening news. Meanwhile the daily war was poverty that kept the elevator broken and the exit rusted. Power showed its teeth in a hundred small ways: a landlord who never fixed the stairwell light, a council that cut the inspection budget, a patrol that treated a hallway like enemy ground. The song answers without a sermon. It names the mistake we keep making. A little might does not equal right.

And I hope and pray—oh please let the children play.

Out of that neglect came an art form that refused to be quiet. Park jams, breakbeats, turntables plugged into streetlights. And yes, irony is part of the American chord: the bassline Bernard and Nile wrote for “Good Times” became the backbone of a new language. Kids rapped over that groove because the city would not fund music class and would not fix the building and would not stop the bus from being a battlefield. They built a culture with what the world tossed aside.

All of which is why the B-side reads like counsel, not filler. It is a musician’s way of saying the thing the photos already show. Choose the harder easy. Put children at the center. Stop calling payback wisdom. If the club gave us a rehearsal for belonging, the street asked whether we meant it.

It’s easier to love, don’t you see?

Picture a street where a flag becomes a spear. That is the undertow the A-side could not carry. Which is why the B-side exists. “Easier to Love” is not filler. It is counsel. “War is no game you play.”

“Give a person a little might, that don’t make him right.”

“Please let the children play.”

The lyric takes the city-wide we and tells it how to behave when fear gets loud. It asks for restraint when payback feels sweet. It puts children in the center and dares adults to govern their fists.

I hear that B-side through the rooms I have been in. Domestic calls where the air is sharp and everyone is sure they are right. Hallways where I was the only Black kid and the rules shifted under my feet. Squad cars V8 engines wide open throttle where the radio hums, lights flash and you learn quick that might is not the same as right. The song keeps saying the simple thing we dodge: if love is easier, why do we keep making war the easy choice.

Which brings me back to the silence after Utah. I kept trying to file it under optics and sides, under what people will say if I express empathy for a political foe who had no empathy for us. The truth is simpler and harder. Grief does not check party before it sits at your table. It just sits. And if I do not let that human fact lead me, I become what I say I am fighting.

So here is where I stand. The A-side, We Are Family, taught me the power of a chorus. It can steady a baseball dugout and a city. It can make strangers a we for a season. The B-side is the part that keeps a family. It tells you what to do when a microphone turns into a weapon or a flag turns into a blade. It says love first, not as sentiment but as discipline. Love as policy. Love as ritual. Love as the line we will not cross.

I will not turn a body into a prop to win an argument. I will not call vengeance wisdom. I will not lie about what certain ideas have done to people who look like me, who look like you, who love who you love. All of that can be true at once. A chorus once made a city feel like family. Today I need the B-side more. You need the B-side more.

If love is the harder easy, we choose it anyway. For the wives who open doors they never wanted to open. For the children learning new words for forever. For a beautiful land that keeps forgetting it knows how to sing.

I stayed quiet. Maybe that wasn’t cowardice. Maybe that was restraint shaped like love. The B-side taught me to hold the line, wait for truth, and not feed a fire I could not control. So I did.

When the facts landed, the story flipped. The suspect came from the same political house that spent day one blaming the left. Prominent voices started scrubbing posts. Tones shifted from war talk to prayer talk. You could watch the backpedal in real time, from cable studios to timelines. Utah officials said they were flooded with thousands of tips. Commentators who rushed the narrative are now deleting, revising, repenting.

Here is why my silence mattered: it did not add confusion. It kept me from turning a body into a prop for my side. It also offered a path the country could have taken. Hold the line. Get the facts. Then speak. We could have spared this country a s** ton of turmoil with forty-eight hours of restraint. That is not neutrality. That is discipline.

Dr. King called it plain: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” Love here is not softness. It is a hard choice to refuse the easy lie and the cheap score. It is the tough mind and the tender heart working together.

So this is my vow. I will practice the B-side ethic in public, not just in private. I will wait when waiting keeps blood out of the streets. I will speak when speaking protects the vulnerable. I will not mistake a little might for being right. And when the chorus comes back around, “it’s easier to love, don’t you see,” I want to be the kind of man whose silence kept faith with the truth, and whose voice, when it finally entered the room, helped lower the temperature so the country we all ove did not break.

Support Independent Media

You make it Xplicitly clear why music and love are the universal language. All the rest is fear. Thank you.

The thing is: Murder is murder and never right. This Kirk character was vile, hateful, racist, sexist and a shit stirring punk. I only saw, by accident, quotes by him. I have no empathy for his demise. I had empathy for friends, family and community when George Floyd was murdered just a few miles from my home. I have empathy for all those murdered school children and their families. I was horrified by the murders and shootings of the Democratic politicians here in Minnesota. Their dog was even murdered. In my life, I am surrounded by affirming love of every kind. (And great music.) We have a gun violence issue that requires someone’s courage to create law changes. And behind that courage is love.