Politics Ain’t Debate Club. It’s Football.

And Liberals Don’t Know the Rules

If I could travel back in time to high school, I know exactly where I’d find myself. Head down. Mind loud. Obsessed with my dad’s ’68 Camaro. Obsessed with politics. Obsessed with the news.

If I could do one thing, I’d leave a note in my locker. A mystery note. Something that would shock me awake, because I know me better than anyone. And I’d be careful not to bump into my younger self, because I remember the rules from Back to the Future. Touch your own timeline and the whole universe goes sideways.

The note would say this:

You really want to understand politics? Put the Machiavelli book down and join the football team.

Back then I learned my limits fast. I tried to start a Young Democrats club. One person showed up. So I buried myself in what felt honest. I tried to solve the mystery of a Rochester Quadrajet. A carburetor has parts you can name. Problems you can diagnose. A system you can master if you stay patient and pay attention.

Politics is not like that now. Those Camaros are toys for the rich. Politics is a toy for the rich too, after Citizens United turned money into speech. And newspapers that used to feel like public conversation are now designer toilet paper for billionaires to wipe their asses with.

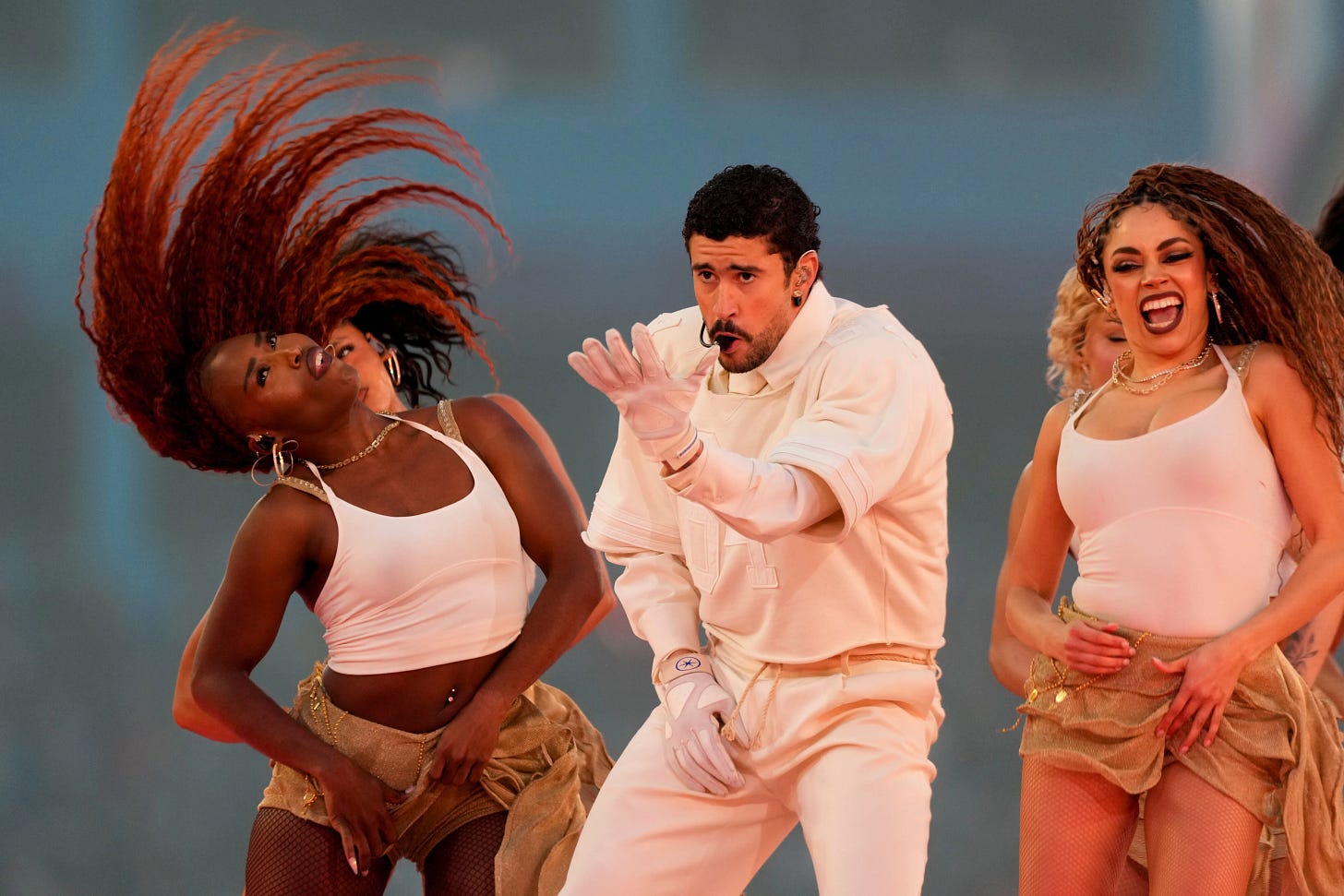

That is why I’m starting with a halftime show.

Bad Bunny steps onto the biggest stage in America and a lot of liberals feel a clean jolt of relief. Validation. This is what America can be. Big, mixed, unafraid. For a few minutes, it feels like the country is not being stolen, just being shared.

MAGA watches the same show and sees politics. Not taste. Not music. Politics. The jeers are not about choreography. They are about the stage. Who gets to belong on it. Whose language counts as normal. Who is allowed to take up space.

And while the crowd cheers or boos, the real winners are the league, the networks, and the ad buyers. They monetize both nervous systems. Bread and circuses is not a conspiracy, it’s a business model. The spectacle gives one side a hit. The outrage gives the other side a mission. Either way, the machine gets paid.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. A lot of liberals mistake cultural relief for structural victory. We feel seen for twelve minutes, then we go back to sleep. Meanwhile the hard right treats the moment as fuel and stays focused on the boring work. Not the show. The plays.

Here’s the point. If you want to understand why far right initiatives keep steamrolling American levers of power, stop watching politics like it is halftime. Learn the game.

TLDR

Liberals watched the halftime show and got that dopamine hit: “We’re still America.”

MAGA watched the same show and saw politics: who belongs, who runs the stage, who gets to define “normal.”

The league, the networks, and the ad buyers cashed in on both reactions. Bread and circuses keeps the crowd loud and the turnout tired.

Republicans aren’t trying to win the argument. They’re trying to win the system: a playbook (Project 2025), a bench (legal pipelines), field position (REDMAP and maps), refs (courts and rules), and a media machine that keeps the team disciplined.

Democrats keep chasing highlights: vibes, norms, and last-minute drives after the clock is almost dead.

If you want to stop the steamroll, stop living at halftime. Learn the rules. Build the line. Show up for the boring work.

Oh hey almost forgot to ask you to restack it restack it restack it and share it with one Democrat who keeps yelling at the TV. Go Paid if you can here:

Why liberals keep missing the football part

If liberal readers feel like hard-right initiatives keep “steamrolling” American institutions, the football metaphor helps because it shifts you from opinion to possession. Who has the ball? Who controls the clock? Who controls field position? Who hires the referees? Who has a bench that can play all four quarters?

Political science and law scholarship increasingly says parties are not just brands or candidates. They are big networks that work together over time: elected officials, donors, advocacy groups, media, and professional pipelines. In other words, the “team” is bigger than the candidates you see on TV.[19]

A liberal audience often understands politics as moral argument plus elections. The football lens adds a second layer: governing capacity. That means the ability to hire people, file lawsuits, write policy, and use institutional bottlenecks once power is won.

A clean “football translation” that matches documented mechanisms looks like this:

Playbook: pre-written policy you can run fast (not invented after Election Day).

Farm system: pipelines that train and place people into judgeships, agencies, and movement institutions, often starting early (law school and clerkships).

Field position: structural advantages and rule design (maps, election administration, preemption, and the geography of representation).

Special teams: targeted, high-leverage plays—lawsuits, redistricting, executive-branch control, and strategic rule changes—that can swing outcomes even without persuasion.

Film room: a feedback loop that tests messages, strengthens group identity, and keeps the coalition aligned.

This frame works for liberal readers because it explains why “being right” or “having better policies” does not automatically turn into power. Politics is an ecosystem sport, not a debate tournament.

They show up with the playbook already written

The clearest example of “we arrived with plays written” is Project 2025 and its main governing manual, Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise.[1] In its own press materials, The Heritage Foundation describes the book as a full guide for the next conservative president. It says it was built by “hundreds” of contributors and is meant to offer both policy proposals and a plan for how to restructure each agency.[2]

Here is the psychological point: readiness is power. If one coalition can treat a transition like a scripted opening drive—staffing, directives, legal strategy, agency reorganization—while the other coalition is still arguing inside its own tent, the first coalition will look “inevitable,” even if public opinion is split.

At the state level, the same “playbook” logic shows up in ALEC (the American Legislative Exchange Council), a national group where corporate lobbyists and state lawmakers work together to write “model bills,” meaning ready-to-file templates.[3][4] A lawmaker can drop one of these bills into a state legislature with only minor edits, which is why you sometimes see the same wording show up in multiple states. Studies that compare bill text have found these template bills can appear word-for-word at meaningful rates and can move through legislatures faster, and in some cases pass at higher rates, than typical bills.[3][4]

Peer-reviewed research adds an institutional explanation for why this works: businesses’ “model bills” are more likely to pass in states where lawmakers have less time and less policy capacity. In those states, legislatures are more dependent on outside groups for drafting and expertise.[4]

For liberal readers, the point is not simply “model bills exist.” The point is that a movement built to copy and repeat beats a movement built for one-time inspiration. Politics rewards scalable systems.

Farm systems and the long game of courts and staffing

Football teams don’t just recruit quarterbacks. They develop linemen, coordinators, and special teams—people you don’t notice until a key play. The conservative legal movement’s version of a “farm system” is often described through the Federalist Society and aligned networks that connect law students, clerkships, donors, and judicial nominations.[6][20]

Reports and research describe how this pipeline works. Networking starts in law school. Chapters replicate across the country. Relationships link young lawyers to judges and elite career routes. A recent dataset paper documents the scale of this activity by cataloging tens of thousands of public events over decades and treating the network as something you can measure.[6]

Why does this matter to the “steamrolling” feeling? Because courts are clock-management machines. Judges last a long time. Court decisions outlive elections and public moods. A coalition that treats judicial selection as a decades-long drive can reshape the rules of the game, not just win one news cycle.[20]

Maps and rules that lock in advantage

Football games are often decided before the snap—by field position and by whether you can force the other side to drive 80 yards instead of 45. In U.S. politics, field position comes from district maps, election rules, and the geography of representation.

A key case study is REDMAP (the Redistricting Majority Project), a 2010-era Republican strategy run through the Republican State Leadership Committee to win just enough state power before the 2010 Census maps were drawn.[7] It focused on winning enough state legislative seats at the right time (the 2010 census and redistricting cycle) to shape maps for a decade. The logic is simple: target a limited number of statehouse races, win control when maps are drawn, and you can lock in an advantage that can be bigger than your share of votes.[7]

The “steamrolling” effect became harder to reverse because, in 2019, the Supreme Court ruled in Rucho v. Common Cause that partisan gerrymandering claims are not something federal courts should decide. That effectively shut down a federal constitutional path for challenging maps drawn mainly for partisan gain.[8][9]

Recent reporting also describes a redistricting arms race, including efforts to redraw maps mid-decade for partisan advantage, with fast-moving lawsuits and high stakes for House control.[10][17][18]

Field position also includes the Constitution’s structure. Political science research argues the Senate’s equal representation of states (no matter the population) has policy effects and can create conservative bias when smaller, more rural states lean Republican.[16]

For liberal readers, the takeaway is hard: persuasion happens on a field that is not neutral—and some of those field dimensions were strategically used and then legally protected.

Special teams: election rules, executive power, and the “referee” problem

In football, special teams are high-leverage and often ignored by casual fans. The political version is rule change: voting access rules, administrative law, and control over enforcement.

A major “rule-change” moment was Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which struck down the Voting Rights Act’s coverage formula for preclearance. That shifted many fights from prevention to after-the-fact lawsuits, changing how voting rights are protected.[11][12]

Another major special-teams play involves the administrative state. In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), the Supreme Court overruled Chevron deference.[13] In plain terms, it made it easier for judges to block or strike down agency rules by saying courts—not expert agencies—get the final word on what many federal laws mean.[13]

The consequence is direct: future presidents can still campaign on big policy promises, but agencies will have a harder time carrying them out, because every major rule is now a bigger lawsuit target. This moves power from regulators to courts, and it rewards the side with the deeper legal bench, the better-funded litigation machine, and the friendliest judges.[13]

How their media machine keeps the team on the same page

A coalition that can coordinate attention can coordinate action. That is what football teams do in the film room: review, refine, repeat. Scholarship on media ecosystems argues the right-wing media environment works differently from the rest of the system. It can create feedback loops that keep people aligned and punish disagreement.[14]

Research on polarization and party asymmetry also suggests the Republican coalition can show stronger ideological discipline and different motivational dynamics around turnout and compromise—factors that affect how reliably a “team” runs its game plan.[15][16]

Put together, the football analogy gets sharper: it’s not only that one side has a playbook. It’s also that their media-feedback system keeps the team running the same install package week after week.[14]

What liberals can do with this frame without becoming what they oppose

For liberal readers, the point of the football metaphor is not to glorify cynicism or promote “win at all costs.” It is to correct a category error: thinking politics is mostly persuasion, when much of modern U.S. power is exercised through staffing, litigation, districting, and procedural leverage.

A structural counter-play agenda that stays inside democratic norms follows from the research:

Treat state politics as a front line, not a side quest.

Accept that after Rucho, map fights are mostly state-based.[8][9]

Build policy capacity that can compete with outside model-bill ecosystems.[3][4]

Invest in durable professional pipelines (a bench) for agencies, oversight, courts, and election administration.[5][6][20]

Stop confusing viral moments with governing power; prioritize repeatable, compounding “yardage.”

The deepest message to liberal readers is not “be more ruthless.” It is: play the whole field. Build the bench. Study the rulebook. Protect the referees by strengthening democratic safeguards. Measure success not only by national headlines, but by whether institutions can still function—and still deliver rights and material stability—after the next turnover.

The Patriots metaphor, and why liberals keep losing in the trenches

Let’s have a little fun and talk about the New England Patriots.

For years, the Patriots ran a dynasty. They did not win because the fans were morally superior. They won because the team did boring things better than everyone else. Film study. Situational football. Clock control. Red-zone discipline. A culture that said, do your job, then do it again.

Then the dynasty ended, like they all do. And this is the part that sounds like liberals right now. The brand still felt unbeatable. The merch still sold. The highlight reels still hit. People kept talking like the old magic would come back if we just found the next Tom Brady, or the next genius coach, or the next viral speech.

Let me make it concrete with a play-by-play from the most recent Super Bowl, with the Patriots as today’s Democrats.

Kickoff: The Patriots run out of the tunnel with a clean story about who they are. The crowd is loud. The branding is sharp. Everybody is ready for the moment.

In politics, this is the big slogan season. Big promises. Big rallies. Big moments where it feels like momentum is enough.

First quarter: Three-and-out. Punt. Another drive, another punt. Nothing is “wrong” with the idea. The problem is the blocking. The other team is already in the backfield, blowing up the timing before anything can develop.

In politics, this is when Democrats win the White House or win a chamber and still can’t move the ball. The Senate rules, the filibuster, and a couple of holdouts turn “we have power” into “we have a press conference.” You watch bills pass the House and die in the Senate. You watch popular ideas get chopped down into smaller ideas that still get blocked.

Second quarter: More punts. You can feel the Patriots trying to be careful, trying not to make mistakes, trying to win the argument of the game instead of the yards. Meanwhile Seattle keeps taking points any way it can, mostly off defense and field position.

In politics, this is the obsession with looking reasonable. “We have to go bipartisan.” “We have to respect norms.” “We have to wait.” And while Democrats are trying to sound responsible, Republicans take points off structure. State laws. Court fights. Maps. Election rules. Small wins that stack up.

Halftime: This is where the crowd argues about the show. Who felt seen. Who felt offended. Who posted what. The league gets paid either way.

In politics, this is the social media halftime show. The dopamine. The clapbacks. The viral clip. The fundraising email. The donation spike. Everybody feels busy. Very little changes on the field.

Third quarter: The Patriots are still scoreless. The quarterback is under siege. Sacks pile up. Turnovers happen. This is what it looks like when your line can’t protect you and you don’t have a quick, simple counterpunch. You keep getting hit before you can even throw.

In politics, this is what it feels like when courts start swatting your agenda like flies. You write a rule, it gets sued. You pass a law, it gets stalled. You try to protect voting rights, but the Supreme Court narrows the tools. You keep saying “the Department of Justice will handle it,” and the clock keeps running.

Early fourth quarter: A fumble turns into a Seattle touchdown. Translation: one mistake becomes a cascade because the other side is set up to capitalize instantly.

In politics, this is when Democrats let a messy slogan, a clipped phrase, or a bad headline become the whole story. One label sticks, the right repeats it, and suddenly Democrats are playing defense against words they did not choose. It does not even have to be true. It just has to be sticky. Republicans pick it up, run it back, and score while Democrats are still explaining what they meant.

Mid fourth quarter: A hit on the quarterback turns into a defensive touchdown. That is the nightmare play in politics too, when pressure turns into a self-inflicted error and the other side scores while you are still trying to explain yourself.

In politics, this is when Democrats accept the other side’s frame. They start answering the question the right wrote. They argue inside the opponent’s language, then act surprised when they lose inside the opponent’s world.

Late fourth quarter: The Patriots finally get into the end zone, but it’s too late. The score looks less embarrassing, but the game has already been decided. That is what “too little, too late” looks like on a national scale.

In politics, this is the last-minute executive action, the late push for voting rights, the sudden urgency after an election has already been lost. It is real effort, but it arrives after the field position is gone and the clock is almost dead.

The Patriots did not lose because their fans didn’t care. They lost because they couldn’t control the trenches, they couldn’t stop the pressure, and they kept giving the ball back.

That is how a lot of liberals do politics. We live on highlights. We wait for the superstar. We argue about vibes. We think the moral high ground is a game plan. Meanwhile, the other side is building the offensive line, recruiting the bench, and drilling the same plays until they work.

Here is the twist. There was a time Democrats understood football, literally and figuratively.

Start with Franklin D. Roosevelt. During the Great Depression, he did not just win an election. He built a machine that could govern. He built a big coalition that held power for decades. He put points on the board with programs people could feel in their bones, like jobs, relief, and Social Security. He also built the bench and kept Congress in play year after year.

So this is not a story about liberals being doomed. It is a story about liberals forgetting what winning actually looks like.

Stop waiting for the next savior quarterback. Build the line. Build the bench. Learn clock management.

Bigger Than Football

But let me tell you the truth. This is bigger than football.

Some of us are watching clips of people getting shoved in the street and saying, “Well, that’s America. Violence is American as apple pie.” No. Not like this. Not as a governing style. Not as a leader’s love language.

Let me be clear. A president who sits across from the world’s most ruthless dictators and gives that little wink that says, “I get it, I wish I could be more like you,” is anathema to everything we claim America is. That is not American exceptionalism. That is surrender dressed up as swagger.

And yes, we have seen this movie before. The crackdowns. The street fear. The smirk of power when it thinks the people are tired. You can find the echoes in Tiananmen Square. You can find them in the Soviet crush-downs in the Eastern Bloc in the 1950s. Different flags, same message: sit down, shut up, and let the strongmen handle it.

If you love this country, the American move is not to become that. The American move is to fight that fascist bullshit with the tools that built the idea in the first place: ballots, courts, organizing, journalism, and the stubborn refusal to normalize what should never be normal.

And this is where I have to bring it back to that kid in the hallway. The kid with a book, a newspaper, and a dream. The kid who thought politics was an argument you win with facts.

Somehow, that kid became the publisher he used to read about. Not because I’m special. Because I’m standing in a house bought with a GI Bill, cobbled together for a generation that did not flirt with Nazis and despots. They fought them. They paid for that fight, then paid again to build a country where regular people could own a home, raise a family, and speak freely without begging permission.

So when people tell you this is “just politics,” hear what they are really saying go back to sleep.

This isn’t just politics. It’s whether democracy is still real. It’s whether the next generation inherits a country where power changes hands by votes, not intimidation. It’s whether the loudest bully gets to rewrite the rulebook while the rest of us argue about halftime.

We can make America American again. Not with nostalgia. With discipline. With turnout. With local fights that don’t trend. With patience that lasts longer than a news cycle.

Because football is just the metaphor.

The stakes are the country.

I’m Leaving That Note

Remember that locker note I wanted to leave my younger self. The one that would shock him awake.

This is me leaving it with you.

If you have the means, don’t clap for democracy and then tip it with spare change. A paid subscription is $80 for the year. That is you buying this work the one thing the other side counts on you not having: attention that lasts longer than a news cycle.

And I’m going to say it plain. If you can spend $80 on a dinner, a bottle, a game, a streaming bundle you barely use, but you won’t spend $80 to help keep a real independent newsroom alive, that isn’t “budgeting.” That is choosing halftime again.

If $80 all at once is a lot, I’m not here to shame you. Take the $8 a month option. That is less than two impulse purchases, and it keeps this press running.

Either way, make a move that your future self won’t have to time travel back to beg you to make.

Sources

https://static.heritage.org/project2025/2025_MandateForLeadership_FULL.pdf

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/alecs-influence-over-lawmaking-in-state-legislatures/

https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2016/07/19/gerrymandering-republicans-redmap

https://www.justice.gov/crt/about-section-5-voting-rights-act

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/17/the-conservative-pipeline-to-the-supreme-court

https://www.propublica.org/article/how-dark-money-helped-republicans-hold-the-house-and-hurt-voters

Thanks for another well written piece. The football analogy works for me. My only complaint is that the Seattle team represented the right wing. Being from Seattle that hurt a little. Just giving you a friendly dig for that.

Brilliant! Another analogy that illuminates systems & shines a light on the reality of the playing field -- although depressing in one sense, it makes sense and lights a fire.