I hear the screams of mothers sacrificing themselves to give their children a chance to cross over, to the other side. I hear the cries of husbands trying to shield their wives and children from the bullets of approaching Confederate soldiers. I hear it happening at an impassable creek, a crossing the Army has already made, after the freed families have been directed to wait their turn and let the troops and wagons go first. I hear and see one family in the water amidst all the chaos, calmly giving their daughter a swimming lesson as bullets fly and people drown attempting to get away, to the other side of the creek. The daughter made it across. She never saw her parents again.

The song “Near the Cross” by the Mississippi Mass Choir plays along like a movie soundtrack in my head as I watch her swim to the other side of the creek. “Rest beyond the river” is the refrain I keep hearing. Those that didn’t make it across did make it across. That little girl finally made it with the help of soldiers already waiting on the far bank, the Army safe on the other side, watching helplessly in horror as the scene unfolded. They were just following orders. General Jefferson C. Davis told them to dismantle the bridge they had used to get across that creek in their march towards Savannah.

Before you keep reading, let me say this plainly.

If your mind placed the villain in gray, you are not alone. If you assumed the men cutting that bridge must have been Confederates, and that any “Jefferson Davis” must be a rebel, that’s the trap this country lays for us. It teaches you to look for evil only on the obvious side, then it asks you to call it history and move on.

This was real. The bridge came up under a Union command, not a Confederate one.

And it gets worse once you learn who that man actually was.

A Traitorous Name

I’m drawing the backstory here from **Bennett Parten’s **Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman’s March and the Story of America’s Largest Emancipation. In that telling, you learn he had a traitorous name. Jefferson Columbus Davis. First and last names that echo the Confederate president, Jefferson Finis Davis. By the time Sherman’s army marched, infamy followed him, and not just because of the misfortune of that name.

Parten lays out what happened in Louisville in 1862. Davis, insulted and humiliated by Union General William “Bull” Nelson, demanded an apology. Nelson dismissed him in front of witnesses. Davis went hunting for a pistol, came back, and shot Nelson dead at the Galt House Hotel. He was arrested, and then he was back in uniform anyway. No trial. No reckoning. The Army needed bodies, and a certain kind of man could always find a reason to be kept.

That’s what protection looks like in America when it decides you’re worth saving. White male privilege did what it has always done. It turned the hanging he deserved into a footnote.

Ebenezer Creek

Then Parten shows you the throughline that makes Ebenezer Creek feel less like a freak accident and more like a pattern with a signature. Davis had been complaining in writing about freed people following the column, calling them a burden, insisting the march could not afford their mouths or their bodies. He started tightening the noose with orders. No wagons for women and children. No horses or mules except for the servants of mounted officers. Deterrence first.

And before Ebenezer Creek ever happened, there were previews. Bridges raised too soon. People stranded while Confederate cavalry hovered at the rear. Panic. Families plunging into water. Some not coming back up. In Parten’s account, Davis kept doing it, again and again, until the creek that would carry the name for what it became.

So when you picture Ebenezer Creek, don’t picture a momentary lapse. Picture premeditation. Picture a man who had already learned he could spill blood in broad daylight and still be protected. Then picture what that does to the people who have no protection at all.

The people in the water had no such shield. No rank. No court. No sympathetic paperwork. No second chances. Just bodies and panic and current. They were freedmen in name, and expendable in practice, people he could see die just as ruthlessly, in broad daylight, with nothing to fall back on.

And Parten makes another point I don’t think we talk about enough.

The soldiers who witnessed it, men who had been marching for weeks, men who thought they knew what war was, came out of that swamp changed. They watched freed people risk everything for freedom, watched mothers and children drown for it, watched families get shattered in front of them, and something snapped into place. Not pity. Respect. A hard, sobering respect. In Parten’s account, you can feel it in the way they condemn Davis, in the way they speak of indignation spreading through the ranks, in the way some of them start saying, in plain language, that anybody willing to die for freedom is entitled to it.

And here’s the part that still burns.

Slavery had been a fact on the page for generations. It could be argued about at dinner tables and filed away as “how it was back then.” But this betrayal in real time, this bridge coming up while women and children were still on the wrong side, this spectacle of people dying for the very freedom America claimed to be marching toward, this is what shocked consciences in a way the abstraction often didn’t. Ironically, it wasn’t the system that spawned the horror that pierced the nation’s nerve in that moment. It was the moment the horror became unavoidable.

And that is why this scene will not let me go.

It is also why I’m done saving it for later.

War After War

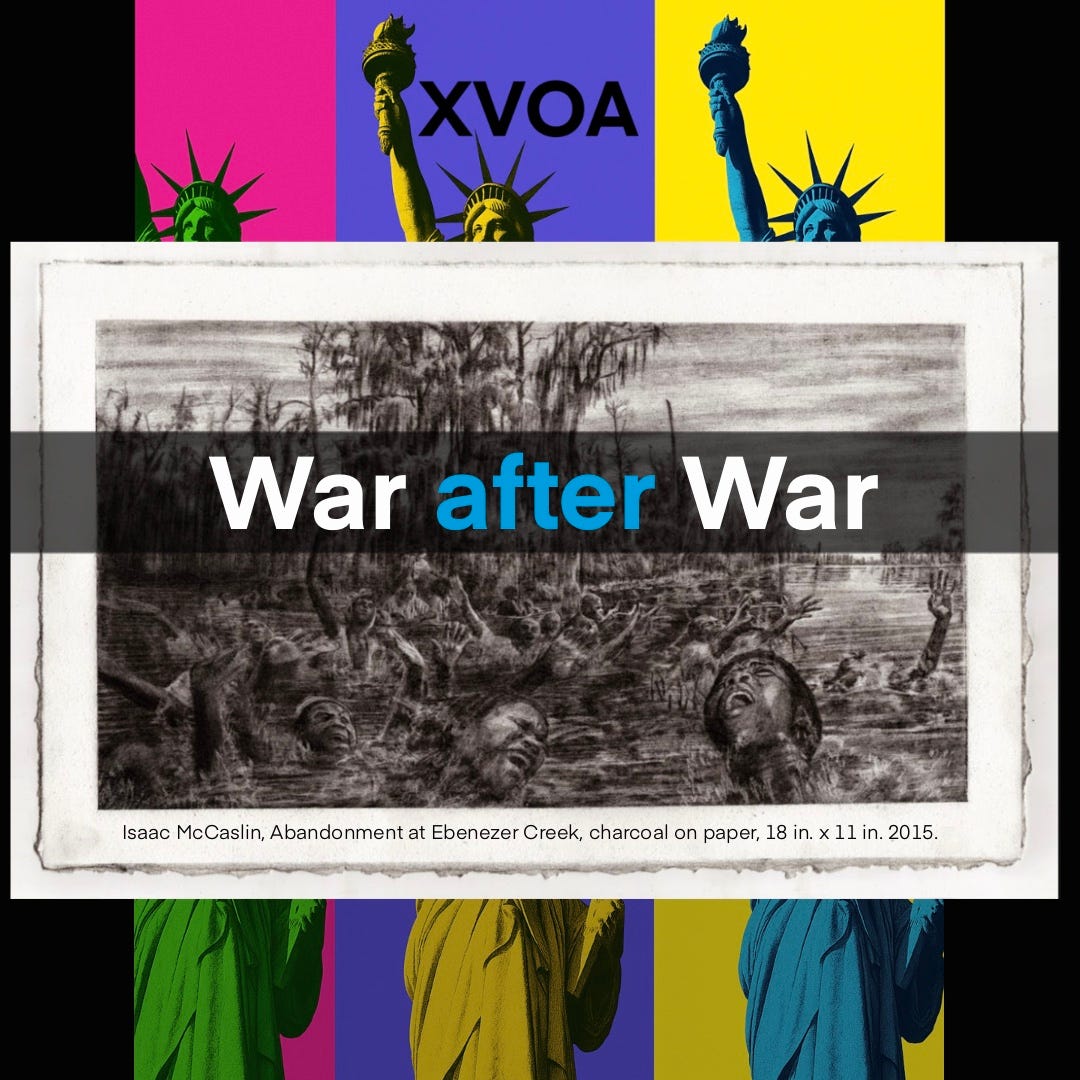

I wrote War After War with this tragedy placed later on. But the voices kept telling me to put it at the opening.

So I intend to open the novel War After War with this, because it was supposed to come later, but the voices kept telling me it belonged on page one. Not as a history lecture. Not as a documentary. As a door you have to walk through, because the rest of the story does not make emotional sense unless you feel what was done to people who had already tasted freedom and were told to wait for it politely.

Those that didn’t make it across did make it across.

I keep coming back to that line because in my head the ones who went under still crossed to the other side. They crossed into witness. They crossed into a place where they could look ahead and see their descendants, generation after generation, still marching. Still pushing. Still insisting on a full human life.

And in that vision they get to watch something else too.

They get to watch their people, in later generations, finally cash pieces of the check America wrote in its founding documents and tried to bounce every time Black bodies stepped up to the counter.

If this section grabbed you by the chest, if it stayed in you longer than you expected, that is the exact reason the Author’s Room exists.

Imagine if you could have been part of a Francis Ford Coppola newsletter while he was conceiving Apocalypse Now. Not the finished film, but the hard decisions, the revisions, the doubt, and the moments the story finally clicks.

Join the Author’s Room tier and you’ll get sneak peek excerpts from the War After War manuscript. You’ll also get the live Q and A, and you’ll be in on the first wave of author signed copies when the finished novel is published.

You are not just “supporting a writer.” You’re helping keep a certain kind of memory alive, the kind that makes it harder to be lied to. If you can do it, come sit at the table. If you can’t right now, stay anyway. I’m still glad you’re here.

This is the history we were never taught, the history that is being systematically removed from advanced curriculum and libraries. Thank you Xavier for refusing to let it die. I hope you find ways to protect your heart as you write it. Thank you.

We learn so much from you.