The Good Crisis. I Kept Quiet. I’m Not Quiet No More.

When Law Enforcement Becomes a Civil War BattleGround

I kept quiet.

I kept quiet in that small Florida town when the NYPD transplant, now teaching at a tech school like he’d been redeemed, flinched and held his disgust in check when I asked him about Serpico. Like the question itself was naïve. Like integrity was for movies.

I kept quiet when the instructor at that little Florida PD drew a Black monkey face on the board and then cut his eyes at me, mischievous, daring me to make it a problem, because I was the only Black officer in that class, and everybody knew it.

I kept quiet when they pulled me aside and warned me about that officer. Every department has one, they said. A walking liability. A civil wrongful death case with a pulse. But they kept him anyway because they needed bodies, after firing the probationary officers who were “too timid,” too careful, too human to fit the moment.

I kept quiet about the other department we all whispered about, the one we called a cesspool. Too Black. Too corrupt. So compromised we didn’t even trust them not to sell our operations and tactics to the corner dope dealer if the price was right.

I kept quiet. Because that’s what you do when you’re trying to survive inside the machine. You swallow it. You laugh it off. You tell yourself you’ll fix it later, fix it from the inside, fix it when you have rank, fix it when you have cover.

I’m not quiet no more, y’all.

Because on January 7, 2026, Renée Good, an American citizen, a neighbor, a mother, ended up dead in the street during a federal operation, and the tape didn’t just show bullets. It showed contempt. It showed the kind of language that slips out when the mask drops. And something in me knew this is not just another case. This is a line. [1, 2, 3, 40, 42]

Good’s spirit has demanded I step up and offer my expertise, little that it is, to this conversation. Not to grandstand. Not to perform. But to testify: this country keeps trying to treat law enforcement as a technical problem when it’s been a moral problem all along.

TL;DR :

If you only have a minute, here’s the map, without spoiling the turns.

The spark: A U.S. citizen named Renée Good is killed during a federal ICE operation, and the public is immediately pushed toward a prepackaged story about what “really” happened. [1, 2, 3]

The tell: A brief moment on the tape, just two words, changes how any honest investigator has to read motive, fear, and contempt. [40, 41, 42]

The real battleground: The fight moves from the street to procedure. Who controls evidence. Who gets jurisdiction. Who gets to declare the ending before a jury ever exists. [6, 11]

The historical mirror: I take you to Boston in 1854, not for a history lesson, but to show what happens when federal enforcement becomes public theater and a community decides cooperation is complicity. [45, 46, 48]

If this feels bigger than one tragedy, keep reading. The pattern is older than any administration, and it is trying to become normal.

The Good Crisis

Let me put the spine on the table, clean and plain.

Civil War 2.0 didn’t start with Renée Good. It started when Charlottesville showed us the country could cheer for political violence again and call it heritage. And the first shots, the first open volley at the constitutional order, were fired on January 6 at the Capitol. That day was a public claim that the state only counts when “our side” wins.

But here’s what I’m saying as a retired cop who has watched the body language of power up close.

This war started in the street. It is going to be decided in the lane. In the traffic stop. In the warrant service. In the raid. In the moment where a badge meets a civilian and the nation has to decide whose fear is allowed to become force.

That’s what I mean by The Good Crisis, and I’m defining it definitively.

The Good Crisis is the moment law enforcement stops being the referee and becomes the battlefield.

Not in metaphor. In procedure. In jurisdiction. In narrative control. In the fight over who gets to investigate, who gets to charge, who gets to see the evidence, and who gets to declare “justified” before the ground has even cooled. [6, 9, 10, 11]

Renée Good’s killing matters because it sits at the intersection of four pressures that, together, turn a tragedy into a constitutional stress test:

Federal force on local ground.

When federal agents operate in a neighborhood, the local community doesn’t experience it as “policy.” They experience it as presence. As occupation. As a new set of rules that didn’t come from their city council, their sheriff, or their consent.The immunity story.

When politicians and federal spokespeople start floating “absolute immunity” language, what they’re really doing is telling the public: this badge cannot be touched. That is a dangerous message in a democracy. It’s not just about one officer. It’s about whether there are two kinds of citizens. Those who can be killed by the state. And those who cannot be judged by it. [9, 10, 11]Evidence control and the poisoning of public reality.

When the federal government takes possession of the key evidence and simultaneously floods the zone with a public narrative, you don’t just risk biasing a jury. You risk breaking the shared reality a jury is supposed to represent. You create a split-screen nation where half the country says open-and-shut and the other half says cover-up, and both sides think the other side is lying. [6, 7]The moral rupture.

Some deaths don’t just spark anger. They create a new kind of clarity. People start speaking in the language of conscience again. Not policy. Conscience. And once that happens, the old tricks don’t work. Not the PR. Not the “wait for the investigation” tone when you’ve already decided the ending. Not the attempt to turn a citizen into a threat to make the state look clean. [1, 2, 5, 7]

So no, I’m not contradicting myself. I’m tightening the timeline.

Charlottesville lit the match.

January 6 fired into the foundation.

And The Good Crisis is the moment the fight arrives at the most intimate American institution of all: the right to use force in the name of the law.

That’s why this feels like the Fugitive Slave Act era. Not because history repeats cleanly, but because the structure repeats. Federal power reaches into a community to enforce a contested moral order. Local people resist, sometimes with witnesses and whistles, sometimes with bodies in the street. The federal government responds with spectacle and certainty. And the state is left to decide whether it will submit, cooperate, or draw a line that forces a national reckoning. [45, 46, 48]

What comes next is the hard part. Not the outrage. The mechanics.

Because the real battleground is going to be who gets to prosecute reality.

Before you keep going: Restack. Restack. Restack.

It costs you nothing. One click.

And if you’ve got 50+ subscribers, your restack is not “support.” It’s a megaphone. It can put this in hundreds or thousands of inboxes from people who would never find it otherwise.

Don’t let this get buried. Restack it, add one line if you can, and share it out.

What Happened on That Street

On the morning of January 7, 2026, ICE agents were conducting a targeted immigration enforcement operation in a Minneapolis neighborhood. Renée Nicole Good, 37, a U.S. citizen and not an intended target, stopped because her neighbors were being arrested. She and her wife reportedly brought whistles, the kind of neighborhood warning system people use when they believe a federal operation is about to swallow the block. In other words, she shows up as a neighbor and a witness. Not a suspect. [1, 2, 3, 5]

Multiple videos emerged, including a roughly 37-second clip believed to be recorded by the shooting agent, ICE Agent Jonathan Ross. In that clip, Good is seated in her Honda Pilot SUV while Ross circles close, phone out, filming. Good is calm enough to say, “That’s fine, dude, I’m not mad at you.” Another agent approaches and screams for her to exit the vehicle, profanity included. Under pressure, with agents around the car, Good’s SUV begins to move. She reverses slightly, then turns the wheel and pulls forward in what my research characterizes as an attempt to leave the scene, not an attempt to attack. Someone in the background shouts, “Drive!” [40, 41, 42]

As she pulls forward, one officer is positioned in front of the SUV. He draws his firearm and fires multiple rounds through the windshield from close range. Other bystander video aligns with this sequence, showing an agent grabbing the driver-side door handle, the vehicle inching forward, and another agent firing. The event is over in seconds. Good’s vehicle continues down the block and crashes after she has been struck. [2, 6, 40, 41]

This is the factual core that matters for everything that follows. The available video evidence and witness descriptions, as my research summarizes them, do not show Good ramming or striking an officer with her vehicle. A retired police lieutenant who reviewed footage is quoted as saying her maneuvers were “not aggressive,” and that “normally you wouldn’t want to be standing in front of a vehicle,” which puts officer positioning squarely on the table. Witnesses also describe Good’s SUV as effectively hemmed in by multiple agents with guns drawn who tried to open her door before she drove off. The picture that emerges is not a woman charging. It is a woman trying to get out of a tightening circle. [2, 6, 12]

Then the narrative war begins. Federal officials frame Good as the aggressor, including claims of “domestic terrorism” and claims she ran over an officer. Local officials reject that framing, and other bystander videos corroborate the witness version over the federal claims. [6, 7]

The Two Words That Changed the Legal Weather

Immediately after the shots, the Ross video captures a male voice, presumed to be Ross, muttering “fucking bitch” as Good’s SUV rolls away. My research notes Ross was only grazed or slightly brushed, kept his balance, didn’t drop his phone, and instead of pain or shock, the record captures contempt. That’s why those two words became a legal and psychological accelerant, not merely a vulgarity. [40, 41, 42]

From a legal standpoint, the phrase functions like a crack in a mask. My research leads me to highlight several ramifications:

State of mind evidence (anger vs. fear). A jury is always asked to weigh what was reasonable in the moment. A spontaneous slur right after firing invites the question of whether fear was driving the trigger, or whether contempt was.

Charging implications. My research ties this kind of language, in context, to arguments about malice or recklessness in the state-of-mind analysis that prosecutors use when deciding whether a case lives in murder, manslaughter, or no-charge territory.

Public trust damage. Even before a court rules on admissibility, a statement like this becomes part of the moral record. It reshapes what the public believes they saw.

Why This Immediately Became a Federal vs State Collision

My research doesn’t treat this as only a use-of-force controversy. It describes a federal posture that framed the shooting as justified and includes high-profile public talk of “absolute immunity” from state prosecution. [9, 10, 11]

Minnesota’s response is equally direct. The Hennepin County Attorney and Minnesota Attorney General announce a joint state investigation, explicitly stating jurisdiction is clear and rejecting the “absolute immunity” claim as legally baseless. [6, 11]

And my research gets concrete about the procedural choke point. The FBI blocks Minnesota’s BCA from access to evidence and witness interviews. Minnesota officials respond by launching a parallel investigation and setting up an evidence portal to solicit public submissions, an extraordinary workaround for being locked out. [6]

The Investigation War

After the shots, the next fight isn’t just about what happened. It’s about who gets to decide what happened, and who gets to say it first, loudest, and most often, before a jury ever exists. Federal officials and aligned voices move quickly into the language of weaponized vehicle and immediate justification, while national political figures lean into immunity talk, positioning the outcome as settled before the investigative machinery has even spun up. [9, 10, 11]

Then comes the custody-of-truth problem: evidence control. The Minnesota BCA is initially invited into a joint probe and then, by the next day, is abruptly blocked from access to evidence and witness interviews. Minnesota’s response is a parallel investigation with a parallel evidence portal. [6]

Put all of that together and The Good Crisis becomes definitional, not poetic: a citizen is killed in a federal operation; the federal side moves to narrate exoneration early; the evidence pipeline is controlled or narrowed; and the state is forced to build an alternate investigative record from the public just to preserve the possibility of accountability. [6]

The Spectacle

Here’s what people miss when they say, “Just watch the video.”

In this country, video doesn’t just document events. Video creates verdicts. And when the state decides to lean on a tape instead of procedure, you’re no longer watching evidence. You’re watching a spectacle designed to settle the story before the law can speak. [7, 40, 41]

That’s what happened here. The footage didn’t simply emerge. It was released into the bloodstream of politics. It was used to frame the incident as justified, while the inflammatory audio further intensified public reaction and legal stakes. [7, 40, 42]

But the spectacle has a problem it can’t solve.

The same video that gets used to declare exoneration also carries something prosecutors and jurors can’t un-hear: that spontaneous utterance, “fucking bitch,” the sound of contempt slipping out while the camera is still rolling. [40, 41, 42]

So now we’re in the strangest American place: the state tries to use video to end the conversation, and the video itself forces the conversation wider.

That’s the mechanism that turns an incident into a crisis. Not just the killing. The performance after the killing, the rush to narrate, the rush to immunize, the rush to make the public pick a side before a single subpoena is served. [7, 9, 11]

Boston, 1854: When Federal Enforcement Became Theater

If you want the clean historical mirror for The Good Crisis, it’s the Fugitive Slave Act era, because that law turned federal enforcement into a moral referendum on Northern streets. Federal law required escaped enslaved people be returned, overriding personal liberty sentiment and statutes in free states, and Boston viewed the mandate as odious and illegitimate even while federal power insisted on compliance. [45, 46, 48]

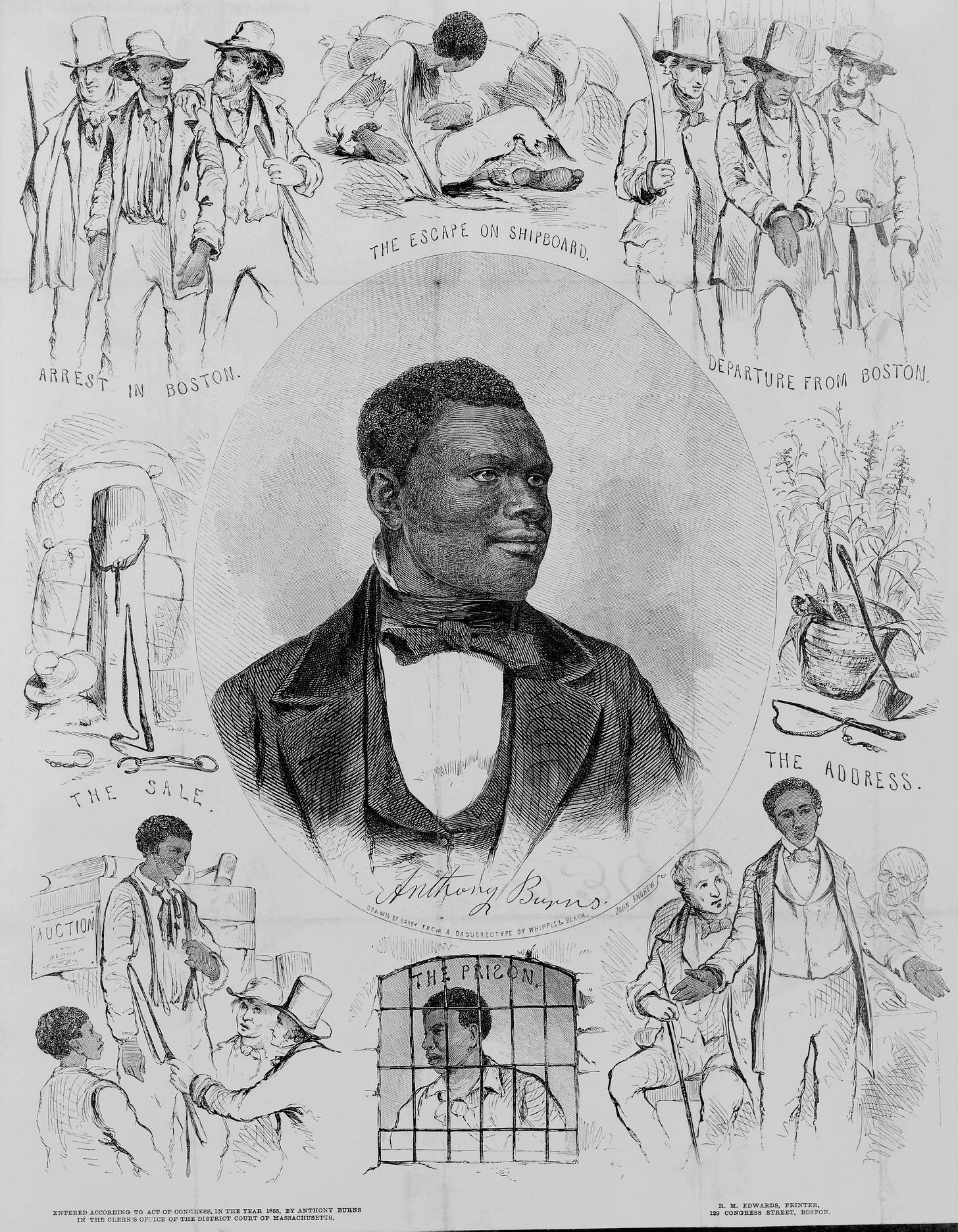

Anthony Burns was a 20-year-old enslaved man who escaped from Virginia to Boston. In May 1854, federal marshals arrested him under the Fugitive Slave Act to return him to his enslaver, and the city erupted into a showdown between federal authority and local resistance. [45, 46]

What made Burns a national rupture wasn’t just the ruling. It was the staging. News spread via broadsides, and the Boston Vigilance Committee poster blared “A MAN KIDNAPPED!” summoning people to Faneuil Hall and framing the arrest as a direct affront to Massachusetts. [45]

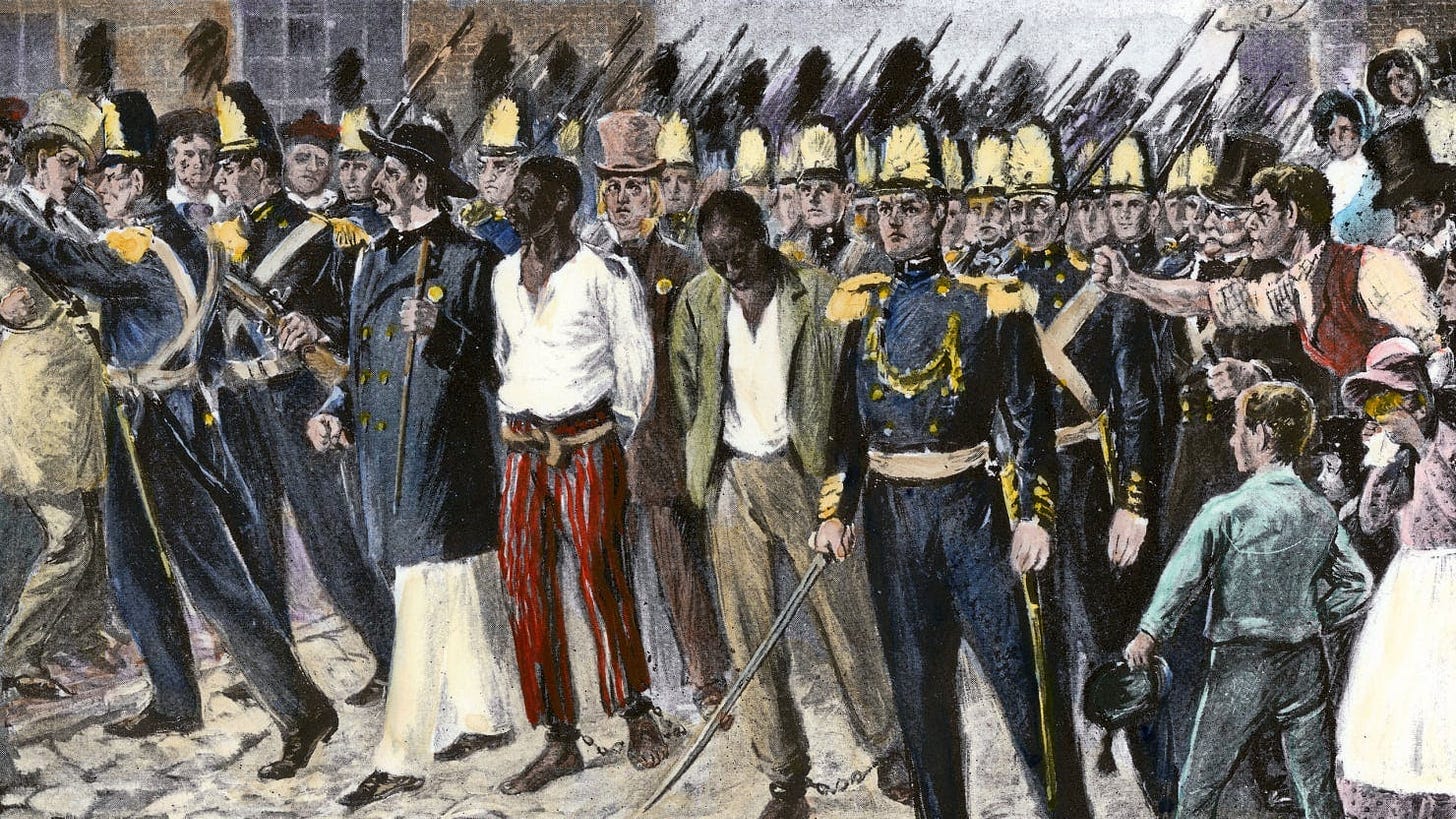

Then came the street theater that burned itself into memory. On June 2, 1854, about 50,000 people lined the streets for what accounts call a “vile procession.” Burns was marched in shackles, surrounded by soldiers, U.S. Marines, federal marshals, and deputized men. Businesses shut down, bells tolled, mourning drapery appeared, even a coffin labeled “Liberty,” and crowds shouted “Kidnappers!” [45, 48, 49]

The federal government engineered that intimidation. President Franklin Pierce ordered U.S. Marines and artillery to Boston to ensure the Fugitive Slave Act was carried out, and the city cooperated with police and militia after a prior violent courthouse assault. One account described Boston as under martial law. [45, 48]

Now watch the parallel structure, not the surface details.

In Minneapolis, Good was not the target of the federal operation. She stopped because neighbors were being arrested, with whistles in hand, positioned in my research as a concerned neighbor or legal observer. Video and witnesses describe her as calm, not aggressive, and trying to leave when agents swarmed her SUV. My research states there’s no indication she rammed or struck an officer. [2, 6]

And just like Boston, the real crisis blooms after the street moment, when the enforcement action becomes a fight over legitimacy. The administration orders the FBI to take exclusive charge of the investigation and bars Minnesota authorities. The local prosecutor challenges immunity talk. A portal is created for citizen-submitted evidence. [6, 11]

Here’s the deepest correlation: when enforcement becomes theater, the public stops arguing policy and starts arguing morality. [45]

That’s why I’m calling this a civil war battleground and not a mere scandal.

Civil War 2.0 is not lines of soldiers in gray and blue. It’s lines of people living inside different edits of the same event. Different captions. Different “facts.” Different villains. Different heroes. It’s information war.

In information war, truth is not only what happened. Truth is what the public can be trained to accept as normal. Who gets believed. Who gets doubted. Who gets framed as threat. Who gets framed as protector. That is why video matters so much now. Video is supposed to settle reality, and instead it gets used to split reality. One side sees proof. The other side sees propaganda. Both sides believe their eyes, even when the story around the footage is doing the real work. [7, 40, 41]

That’s the deeper fight underneath The Good Crisis. Not only whether a shooting was justified, but whether procedure even gets a chance to speak before the megaphone declares the ending. Who controls the evidence. Who controls the release. Who controls the language the public repeats. When the government tries to prosecute reality through narrative instead of investigation, it’s not just managing a news cycle. It’s testing whether the Constitution still has authority over the story we are ordered to believe. [6, 9, 11]

So when I say “civil war battleground,” I mean this is where the war of stories touches flesh. It touches streets. It touches juries. It touches whether a citizen can be killed and then rebranded into a threat so the system can sleep at night. Watch how it rhymes.

What Boston Did Next

Boston didn’t just mourn Anthony Burns. Boston changed the rules of the game. After the rendition, Massachusetts turned its rage into institutional retaliation: the state ousted Judge Edward Loring from his Massachusetts post and moved to pass new laws designed to prevent that kind of federal overreach from being executed so smoothly again. [45]

Then the deeper turn happened, the one that matters for your thesis. The Burns spectacle produced a broad moral shift, described as indignation, shame, and soul-searching across segments of society, forcing people to decide whether “order” was worth complicity. [45]

Once that moral line hardened, enforcement became politically radioactive. My research makes the point bluntly: after 1854, no other escaped enslaved person in New England was successfully sent back, because the political cost and public fury became too high. [45]

That’s the lesson people skip. The Fugitive Slave Act did not collapse because it was suddenly argued better. It collapsed because enough Northern communities began to treat cooperation as surrender.

Now take that Boston aftershock and lay it over Minnesota.

In Minneapolis, the shooting is only the first chapter. The second chapter is the tug-of-war over the investigation. My research describes federal restriction of state investigative access and Minnesota’s counter-move with a parallel investigation, an evidence portal, and an alternate record built outside federal permission. [6]

And Minnesota is saying, out loud, that it intends to stay in the fight. My research states the jurisdiction claim plainly and rejects the “absolute immunity” posture as legally baseless in the way it’s being deployed. [6, 11]

So “What Boston did next” is the blueprint we need in this moment.

Boston’s move was to turn moral disgust into sustained, procedural resistance until enforcement broke. Minnesota’s version will look like jurisdiction asserted, evidence demanded, local refusal to cooperate with impunity, and institutions taking sides in public. When compliance collapses, legitimacy collapses with it. That’s how a law enforcement incident becomes a national reckoning.

Use of Force

Let me talk like a street cop for a minute, because Payback Policy isn’t just speeches and slogans. It’s decisions made at street level by people with guns who believe the system will protect them no matter what. And when that belief hardens, it always leaves the same thing behind: a crime scene. Not just blood on asphalt. A broader contamination. A story that has to be forced onto the public, because the facts won’t stay in their place.

Here’s the use-of-force rule most civilians never hear, but every working cop knows in their bones: don’t create the danger and then call the danger “self-defense.” In my research and in my experience as a police officer who has been in similar situations, the moment Good tries to move, after she’s sitting there calm enough to say, “I’m not mad at you,” while an agent circles her SUV filming, an officer positioned in front of her vehicle opens fire through the windshield at close range with a camera in hand instead of making an attempt to avoid the oncoming vehicle. [40, 41, 42]

My research doesn’t treat that positioning as neutral. It records a retired police lieutenant’s read: Good’s driving wasn’t “aggressive,” and “normally you wouldn’t want to be standing in front of a vehicle,” implying the officer’s own positioning may have created the peril he later claimed. It also describes witnesses saying multiple agents had guns drawn and attempted to yank open her door before she drove away, so the “threat” is happening inside a compression chamber the agents themselves built. [2, 6, 12]

Now watch the unforced error stack up.

Unforced error #1 is tactical: the lane decision.

Unforced error #2 is verbal, and it’s the one that changes the legal weather: “fucking bitch.” [40, 41, 42]

Unforced error #3 is escalation culture. Profanity-laced commands. A scene that gets tighter and hotter instead of calmer.

And then unforced error #4 happens after the smoke. It’s the rush to narrate. Call her a terrorist. Call it justified. Call it finished. [6, 7]

That’s the trap of payback: once you label first, you are forced to defend the label. Payback doesn’t like accountability because accountability feels like humiliation. So it doubles down. It hardens. It dares the public to accept the story over their own eyes.

PAYBACK ALWAYS LEAVES A CRIME SCENE.

Because the crime scene isn’t only the body. It’s the institutional behavior afterward. It’s the scramble to control evidence, control investigators, control the story. My research describes Minnesota officials asserting jurisdiction and responding to federal restriction with a parallel investigation and a public evidence portal. [6, 11]

This is where the psychological shadow becomes procedure.

The Jungian “shadow” is the part of us we don’t want to admit is in us. The fear. The cruelty. The hunger for control. We push it out of sight, then under stress it leaks out sideways as blame, overreaction, and a need to feel innocent even while doing harm.

So the shadow move isn’t simply “they’re mean.” The shadow move is this. Make force untouchable by making the process impossible.

If you can:

pre-frame the victim as a threat

pre-frame the shooter as a hero

restrict who can investigate

flood the zone with the “case closed” story

you’re not just protecting one agent. You’re protecting a self-image. And you’re testing whether the public still believes in the basic democratic idea that power can be reviewed. [6, 9, 11]

That is the hinge where a mistake turns into a moral injury for the nation.

Because now we’re not only talking about ballistics. We’re talking about what kind of person the system produces when it rewards fear, valorizes dominance, and then calls the public “un-American” for asking questions. We’re talking about a psychology that believes contempt is permitted because consequences are optional.

So yes: The Good Crisis isn’t just the moment a woman died. It’s the moment a system tried to convert a tactical mess into a moral victory, while the video kept whispering the truth underneath the talking points.

That’s why I keep calling this a crime scene. The body is the first evidence. The cover story is the second.

That’s not strength.

That’s a fourth-quarter collapse in slow motion.

Ghosts, and the Hymn We Owe the Future

Renée Good has been walking through my house like a draft you can’t locate. Not Hollywood haunting. The kind that shows up while you’re washing dishes, while you’re pretending the day is normal, while you’re doing that old American thing of trying to outscroll grief and pretend it don’t hurt now when it most definitely does. And then the moment hits, not like furniture flying, but like faith cracking. Because once you’ve seen the state take a life and then rush to narrate it clean, you start hearing a question under every headline: who’s next, and who gets to call it justified?

And I know why this one got in. Her name is Good. That’s not just a name in this story. It’s an indictment. It’s the unconscious knocking on the door saying you can’t keep calling evil “order” and expect your soul not to revolt. You can’t keep treating a mother’s death like a political inconvenience and expect the ghosts not to gather.

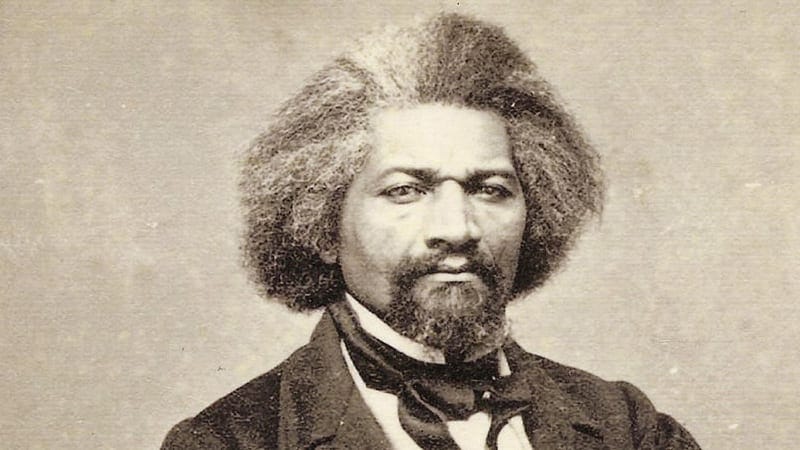

History tells me I’m not crazy for feeling haunted. Frederick Douglass did not talk about John Brown like a man safely buried in the past. If you don’t know the name, John Brown was a white abolitionist who chose armed rebellion against slavery, most famously at Harpers Ferry, and was executed for it. [52, 53]

In an 1874 newspaper piece, Douglass said it plain:

“He was with the troops during that war, he was seen in every camp fire, and our boys pressed onward to victory and freedom, timing their feet to the stately stepping of Old John Brown as his soul went marching on.” [52]

That is what I mean by a holy haunting. The dead show up when the living have not finished the work. And that is what Renée Good is doing to us now.

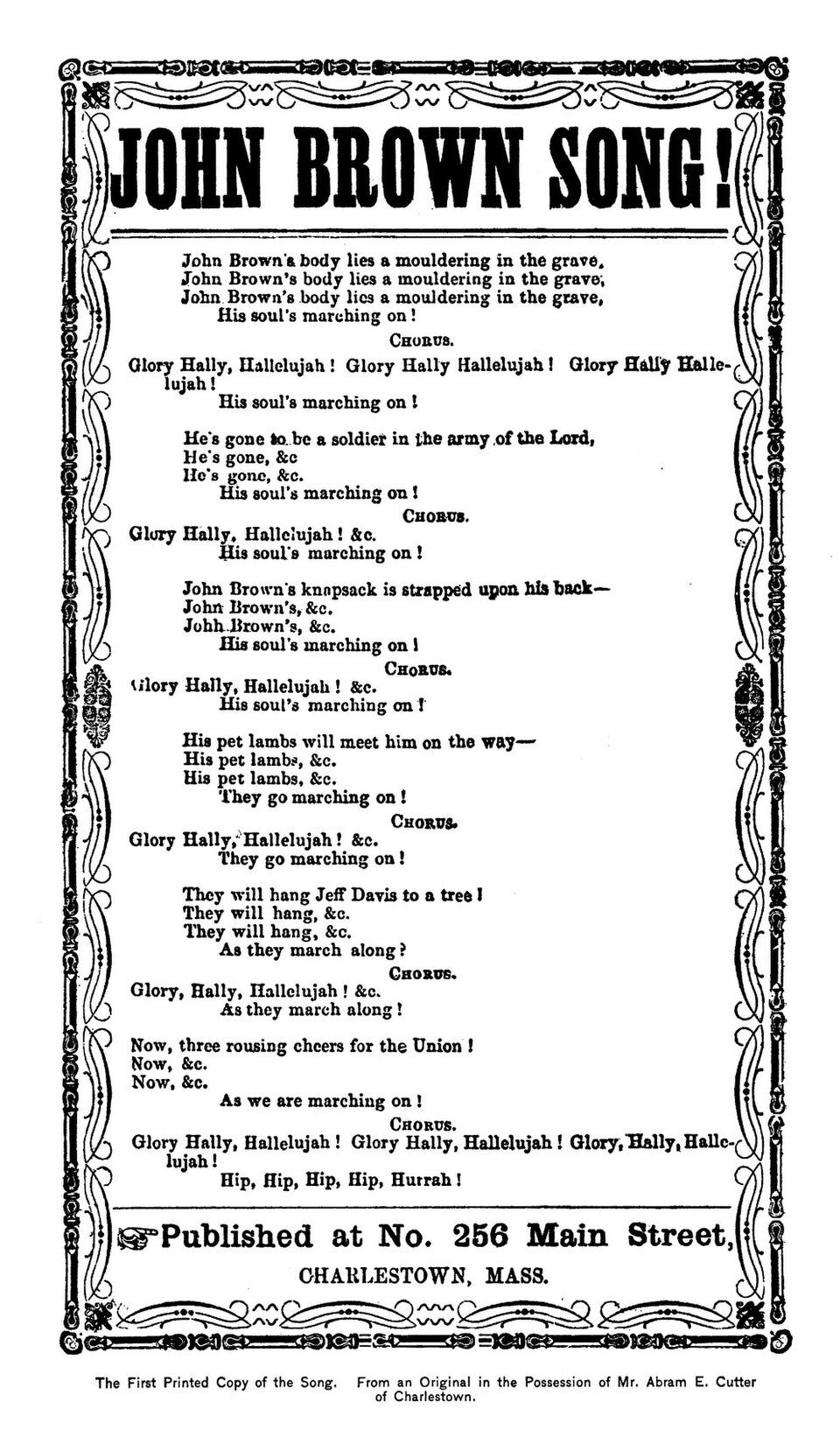

And the soldiers had a way of saying the same thing without giving a speech. They sang it. “John Brown’s Body.” It was a marching song, a footstep you could hear coming, and the chorus did what history always does when it’s finally honest. His soul goes marching on. [50]

Then something even more American happened. The tune did not stay in the camp. It moved upward, from the mud to the choir loft. Julia Ward Howe heard that same melody and wrote new words to it, words that turned a soldier’s chant into a national prayer, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Same music, different language, and the same moral claim underneath it. [51]

So here’s my prayer, and I’m going to say it like a prayer because I don’t have the patience for fake neutrality anymore.

I pray that a hundred years from now, when this era is finally printed in history books like a bad dream we survived, our grandchildren won’t just memorize dates. I pray they’ll learn the Good the way we learned the flag. I pray they’ll pledge allegiance to the Good, not as a slogan, but as a refusal to let power lie about what it did. I pray the Good becomes a standard higher than party, higher than tribe, higher than the appetite for payback.

And I pray that the way “John Brown’s Body” turned into “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” becomes the blueprint for what comes next. A melody that started in the dirt, got lifted into a hymn, and then carried a whole people through fear with one shared sentence they could sing. [50, 51]

So let me ask you to picture it, just for a few seconds. A better life for your grandchildren. A country that finally learned what the word “citizen” means. A crowd where old and young are not enemies. Where Black and white are not trapped in a permanent argument about whose pain counts. Where men and women can stand shoulder to shoulder without fear. Where Democrat and Republican can disagree about taxes and still agree about the sacred line the state may not cross.

And in that future, they are singing something together. Not a party song. Not a campaign chant. A moral song. A song called “The Good.” A hymn that teaches the next generation the lesson we keep trying to forget. The state does not get to kill and then bully the nation into calling it normal.

Then I want that vision to drop back down into the street, where protest is not polite and grief doesn’t have a filter. That’s where “Good Times” by Chic comes in. Not as escapism, but as strategy. A street anthem that carries two truths at once: we are in pain, and we are still alive. We can dance and still refuse. We can sing and still fight. We can turn the block into a choir and make the whole country hear us. [54]

Because that’s what a hymn is, when it’s real. It’s a promise you can sing when you’re afraid. It’s a way of keeping your spine when the noise is trying to steal it.

So if you felt Renée’s ghost too, don’t treat that as weakness. Treat it as instruction.

That’s why I want “Good Times” in the street right now. Not as denial. As defiance. A beat that keeps our spine straight. [54]

The future will ask one thing. Did you go quiet, or did you keep time.

These Are The Good Times.

If that one line on the tape, “fucking bitch,” hit you in the chest, good. Don’t numb it. That is your conscience still working. [40, 42]

And if you’re tired of billionaire-owned media treating deaths like this as a weekend inconvenience, burying the story the minute it gets uncomfortable, then help me keep a light on it. [1, 7]

I’m not ashamed to ask for support. I’m proud to do this for a living. Not to fund a yacht. To keep a roof over my head while I do the work they keep refusing to do.

If you’ve got a little room in your budget, become a paid subscriber so this stays free for people who are strapped right now. That’s the deal. Your paid support keeps this work out in the open.

SOURCES:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2026/01/09/ice-shooting-victim-minneapolis/

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/jan/09/white-house-minneapolis-ice-killing

https://www.notus.org/trump-white-house/jd-vance-fatal-shooting-minneapolis-ice-far-left

https://people.com/jd-vance-blames-renee-nicole-good-for-ice-death-11881946

https://transcripts.cnn.com/show/ctmo/date/2026-01-08/segment/01

https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Civil_War_AdmissionReadmission.htm

https://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/document/forty-acres-and-a-mule-special-field-order-no-15/

https://www.georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/march-to-the-sea-ebenezer-creek/

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/ebenezer-creek-massacre/

https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/port-royal-experiment

https://blackpast.org/african-american-history/port-royal-experiment-1862-1865/

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/reagan-speech-at-neshoba/

https://www.newsweek.com/karoline-leavitt-cross-necklace-2096037

https://nlihc.org/resource/democrats-take-control-white-house-senate-and-house

https://abcnews.go.com/US/video/cellphone-video-officer-shows-moment-fatal-shooting-renee-129066992

https://people.com/renee-good-last-moments-video-footage-11882682

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2026/01/11/ice-shooting-renee-good-reactions/

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2026-01-10/new-video-shows-renee-good-shooting-ice-agent/106216052

https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/only-the-beginning-of-difficulties-2010-09-01

https://revolutionarycorridor.org/the-fugitive-slave-act-and-the-case-of-anthony-burns/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown%27s_raid_on_Harpers_Ferry

The original civil war never ended. The South, angry about the surrender, went underground. The Heritage Foundation along with the KKK were born.

This has been the plan all along. Kill the government within.

Well... you certainly put a lot of research into this. Almost like investigating the evidence in a crime. Wait... you are investigating the evidence in a crime. And thanks for all the sources. For me, sources verify that you've done your homework. Thanks for a compelling story.