The War We’re Not Allowed to Call a War: Caribbean Strikes, Venezuelan Dreams

Quagmire for Empire (Part 2)

When I finished this thumbnail, I caught myself thinking, “Damn, that’s a powerful Vietnam shot.” I knew better but still I was being seduced by the rifles, the Vietnam like jungle scenery, the hollow worry in the villagers’ faces, it all scans as 1960s Southeast Asia at first glance. Then the caption in my head snapped me back to reality: it’s not Vietnam, it’s the Philippines, fifty years earlier, same empire, same stance, same terrified civilians standing on soil that already knows it will be asked to swallow more bodies.

As I laid the words Philippines. Vietnam. Iraq. Afghanistan. across that image, man, something in me tightened. This one got under my skin in a way no other thumbnail has, maybe because it forced me to admit how predictable this rhythm has become. I could almost feel the dead in the ground beneath their feet, lining up with the dead in every other “police action” we swore would be the last. The longer I stared at it, the less it felt like design and the more it felt like a warning: the past isn’t just echoing, it’s rehearsing us for the next act.

Congress Reclaims Its War Powers

Looking at that pattern on repeat, it’s no accident that even Congress is starting to flinch. After years of waving through whatever the commander-in-chief wanted, a bipartisan group is finally trying to tap the brakes: Senator Rand Paul has joined Democrats to dust off the War Powers Act and challenge Donald Trump’s latest moves toward Venezuela. The Trump administration has been conducting lethal strikes on alleged narco-traffickers and even threatening a land invasion of Venezuela without congressional approval .

Lawmakers led by Sen. Tim Kaine warn that Trump is overreaching and edging the U.S. into “another forever war,” reminding him that the Constitution grants only Congress the power to declare war. As Kaine put it bluntly on X this week, “The Constitution gives Congress—and only Congress—the power to declare war. Trump’s illegal boat strikes and threats of land invasion in Venezuela are a clear overreach of power. I filed a bipartisan War Powers Resolution to stop Trump from starting another forever war.”

Kaine has been sounding this alarm on multiple fronts, from Iran to Venezuela. Introducing his latest Iran-focused War Powers effort in June, he warned, “I am deeply concerned that the recent escalation of hostilities between Israel and Iran could quickly pull the United States into another endless conflict… The American people have no interest in sending servicemembers to fight another forever war in the Middle East.”

On the Republican side, Sen. Rand Paul is breaking with his party to echo the same constitutional line. “The Constitution says the prerogative to declare war… is solely from the Congress… There is no constitutional authority for the president to bomb anyone without asking permission first,” he told Fox News Digital, warning that Trump’s unilateral strikes risk normalizing executive war-making without any vote. He’s also taken that fight to the broader debate over alliances, arguing in a recent op-ed that even NATO’s Article 5 “does not supersede Congress’s responsibility to declare war or authorize military force before engaging in hostilities.”

Taken together, this rare alignment between Kaine and Paul signals Congress “growing a pair,” so to speak, after years of mostly bowing to Trump’s militaristic impulses. It harkens back to the post-Vietnam mood that produced the 1973 War Powers Resolution—an era when lawmakers, burned by quagmires, finally tried to claw back their constitutional role before the next forever war got written into law.

Echoes of Past Quagmires

American history is littered with wars that turned into protracted quagmires despite promises we’d never make the same mistake again. Each time, leaders and the public vowed “never again” only to watch a new conflict unfold with eerie similarities. A few key examples include:

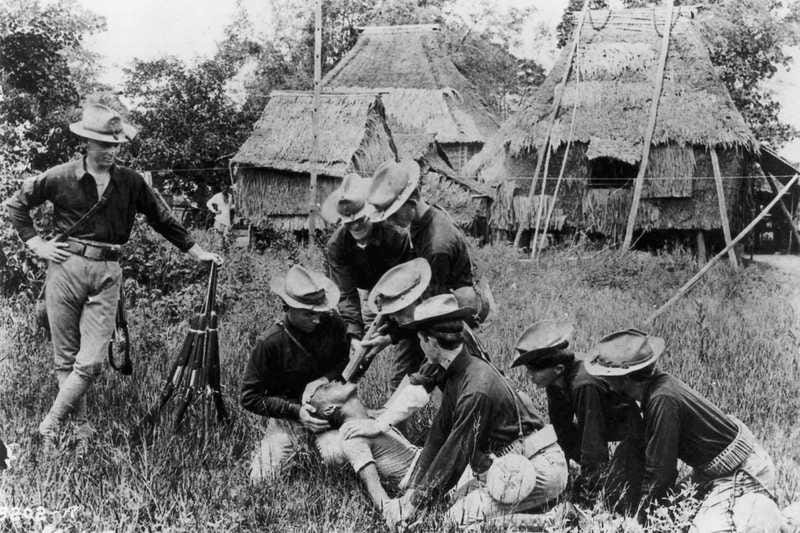

• The Philippines (1899–1902): After the Spanish–American War, the U.S. found itself fighting a brutal insurgency in the Philippines. Filipino revolutionaries who had expected independence instead battled American occupation in a war marked by guerrilla warfare and atrocities .

What Washington dubbed the “Philippine Insurrection” became a years-long quagmire for empire, with U.S. forces resorting to torture (the infamous “water cure”) and causing massive civilian casualties . This early venture in overseas empire-building shocked many Americans and provoked an Anti-Imperialist League at home, which warned that such entanglements betrayed American ideals.

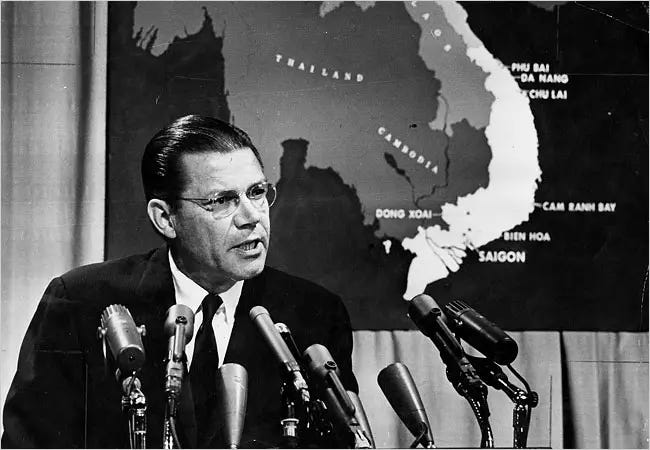

• Vietnam (1965–1973): Despite vows after World War II to avoid messy land wars in Asia, the U.S. escalated a conflict in Vietnam that became the archetype of a quagmire. More than 58,000 Americans were killed, along with millions of Vietnamese civilians and fighters .

U.S. leaders repeatedly misled the public about “light at the end of the tunnel,” while the war dragged on with no clear win in sight. The trauma of Vietnam led to a collective sentiment of “No more Vietnams,” and in 1973 Congress passed the War Powers Act over President Nixon’s veto to restrain future presidents . The new law required presidents to seek congressional consent for extended military deployments, a direct response to the executive overreach that had allowed Vietnam to spiral out of control .

• Afghanistan and Iraq (2001–2021): After the 9/11 attacks, the U.S. plunged into wars in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) with aims of defeating terrorism and spreading democracy. These conflicts soon resembled the quagmires of prior generations. Officials promised quick victories, but instead the missions morphed into decades-long occupations with ever-shifting goals. In Afghanistan, U.S. policymakers repeated many Vietnam-like mistakes—pursuing an ill-defined mission to remake a foreign society, and misleading the public about progress and challenges . A cache of internal documents known as the Afghanistan Papers later revealed that American leaders “deliberately misled the public” about failures, much as their predecessors had done in Vietnam . By the time these “forever wars” wound down, thousands of U.S. troops and hundreds of thousands of local civilians had lost their( lives, and Americans once again were saying it was a mistake to have gotten bogged down so long.

After Vietnam, Congress had intended the War Powers Resolution to prevent such open-ended wars . Yet in practice its impact was limited. Over the ensuing decades (especially in the post-9/11 era), lawmakers often deferred to presidential “gun-slinging” abroad despite the law on the books . Successive presidents sidestepped or ignored Congress’s authority, launching military interventions from Central America to the Middle East under broad executive claims. This history of half-hearted oversight set the stage for Trump’s actions—and Congress’s current wake-up call. The fact that a War Powers showdown is happening again in 2025 underscores how cyclical this pattern has become.

The Forever-War Cycle and the Military–Industrial Complex

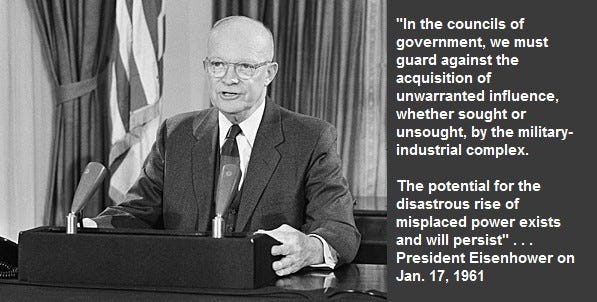

Why do these quagmires keep happening with such predictability? Part of the answer lies in what President Dwight D. Eisenhower famously dubbed the “military–industrial complex.”In 1961, Eisenhower warned that a powerful nexus of defense contractors, military leaders, and politicians could drive perpetual war for profit and power . He noted the “total influence—economic, political, even spiritual” of this alliance is felt throughout the halls of government .

Decades later, his warning seems prescient: the military-industrial complex virtually banks on regular conflict. Defense companies spread jobs and contracts across many congressional districts to secure broad political support . Lawmakers know that backing new weapons programs (and by extension, the wars that justify them) brings money and employment to their home turf . In turn, the Pentagon plans its force structure and budgets on the assumption that every generation or so, America will be embroiled in a major conflict. War, sadly, has become normalized as a kind of default state that keeps the machine running.

This expectation of perpetual war isn’t just an abstract concept. It’s ingrained in military culture. Even as new recruits, we were conditioned to accept a regular rhythm of combat. In boot camp, I vividly recall our drill instructors drilling us with call-and-response cadences that glorified blood and conquest. “What makes the grass grow?” the leader barked. “Blood, blood, blood!” we recruits shouted back in unison. “Who makes the blood flow?” he demanded. “Soldiers make the blood flow!” we answered. The message was brutal but clear. Our drill sergeant even told us flat-out to “expect a war every twenty years.” In other words, each new generation of American soldiers will have its war. This cynical timetable was presented as casually as a training schedule, yet it speaks volumes about how routine empire’s wars have become. The young troops marching out of boot camp are effectively promised that somewhere, sooner or later, they will be sent to fight. And historically, that grim prediction has proven accurate more often than not.

Predicting the Next Quagmire: Fiction or History?

The cycle of American military entanglements has become so routine that even our popular fiction picks up on it. One striking example comes from James Cameron’s 2009 film Avatar, set in the 22nd century. In an early scene, the tough-talking Colonel Quaritch boasts about his past Earthside deployments. He mentions that Jake Sully, the protagonist, “fought in Venezuela,” which cost him the use of his legs, and that Quaritch himself served “three tours in Nigeria” with the Marine Corps . At the time, these lines might have seemed like throwaway world-building with fictional future wars in far-flung places. But they resonated because they felt plausible. In fact, they turned out to be eerily prescient.

Fast-forward to today: Venezuela has indeed become a focal point of U.S. confrontation (with President Trump openly threatening intervention on the pretext of fighting drug traffickers), and Nigeria which is rich in oil and strategic location has been mentioned as a potential flashpoint in great-power competition. It’s as if the screenwriters had a crystal ball. Of course, they didn’t. They simply extrapolated from a long historical pattern of American intervention in the global south. The targets may change, but the underlying impulse (and often the justifications of spreading freedom or fighting “bad guys”) rhyme with the past. When even Hollywood blockbuster dialogue can anticipate real-world policy, it underlines how baked-in these expectations of conflict truly are.

None of this is magic or inevitability; it’s history. And as Dr. Heather Cox Richardson’s work keeps reminding us, you don’t need a psychic to see where American foreign policy is headed. You just need a willingness to read the past honestly. The recurring saga of quagmire for empire that began in the Philippines over a century ago has become so ingrained that recognizing the next iteration is simply a matter of remembering the last. The hope now is that our leaders are finally remembering. By reasserting its war powers authority, Congress is trying to break the pattern or at the very least force a real debate before we tumble into the next predictable disaster. Whether this effort succeeds or not, one lesson shines through: the future need not repeat the past if we choose to heed the hard-earned lessons of history rather than succumb to its ruthless rhythm.

If you’ve read this far, you already know you’re not “neutral” in any of this. Every April, your tax dollars march straight into the veins of the military-industrial complex, whether you cosign the killing or not. If you’re going to be forced to bankroll the bombs, you damn well better be one of the people propping up the voices that refuse to flinch when it’s time to name the lie behind every “police action” and “limited strike.”

Here’s the part nobody likes to say out loud: this kind of work costs time I don’t have unless you help buy it back. Every paid subscription is a few more hours I can steal from side gigs and give to reading the footnotes, chasing the paper trail, and stitching these stories together so you’re not walking into the next war blind. If you feel that pull in your chest right now, that’s your altar call. You’re already funding the war machine. Click the button, become a paid subscriber to XVOA, and help even the score by keeping at least one stubborn, independent voice on the field.

Sources:

1. Fox News – “Rand Paul joins Dems on war powers resolution…” (Dec 4, 2025)

2. American Prospect – “How Congress Got Us Out of Vietnam”

3. News Decoder – “Afghanistan & U.S.: Déjà vu all over again”

4. Truthdig – “Tragic Dawn of Overseas Imperialism” (Philippine-American War)

5. Avatar Wiki (James Cameron’s Avatar) – “Resource Wars” (film dialogue reference)

6. News Decoder – Eisenhower’s farewell address (military–industrial complex)

7. Washington Post/AP via News Decoder – Vietnam and Afghanistan war statistics

Plain text hyperlinks:

https://www.foxnews.com/politics/rand-paul-joins-dems-war-powers-resolution-trump-congress

https://prospect.org/justice/2023-10-20-how-congress-got-us-out-of-vietnam/

https://news-decoder.com/afghanistan-us-history/

https://truthdig.com/articles/tragic-dawn-of-our-overseas-imperialism/

https://james-camerons-avatar.fandom.com/wiki/Resource_Wars

https://news-decoder.com/afghanistan-us-history/

This morning HCR laid out the new 2025 Trump National Security Strategy. Reading it, the pit in my stomach grew. Even on its face, it’s a horror, but, deeper implications are even worse.

It’s a declaration of white Christian nationalism, isolationism, economic colonialism/extraction, and a threat to our neighbors. It insults and turns its back on our once trusted allies while aligning with Russia. It conflates diplomacy with extortion.

It is capitalism and the military industrial complex, Eisenhower warned us about, taken to its worst possible outcome. It’s shameful.

Everything you have pointed is true about the potential of war every 20 years for each new generation. It seems that the need for a “good fight” is always around the corner for those that have the “blood-lust” genes. As a medical person, this takes an emotional and physical toll on the persons involved in the combat and the medical profession to treat the war torn soldiers. It’s also a costly burden on the country’s citizens. At present, our military’s financial budget is in the hundreds of billions per year just to keep our troops trained, provided equipment, and supplies for a potential war or conflict. The conflicts or wars are not just affecting the military’s physical and mental wellbeing, but the secondary infliction of it affects the citizens and families.