The Washington Post Predicted January 6

A Quote So Precise It Feels Illegal to Have Seen It Early

History doesn’t repeat. It rhymes so clean it feels like déjà vu and that should scare the hell out of us.

Here’s my confession before I start pointing fingers: I used to rely on the polite version of history the way people rely on small talk. The version that says the system holds, the adults show up, and the republic always pulls up at the last second. It’s comforting. It’s useful. It’s also a lie we tell ourselves because the truth is heavier than most people want to carry before breakfast.

Plato had a name for it: a Noble Lie, the kind of story a society repeats because it builds faith in institutions. And if you read Dr. Heather Cox Richardson, you already know what happens when that faith turns into denial. She writes history like a daily audit, not a bedtime story.

But I need you to see how the Noble Lie lived inside me.

January 6, 2021. I was in uniform, on break, sitting in a patrol car miles away, watching the Capitol get overrun on a screen. I did what cops do when the air turns strange. I called a coworker to see if riot units were being spun up under mutual aid agreements. He answered like it was nothing, matter of fact, saying there was no problem with these people and, specifically, that they weren’t antifa.

And that’s when something in me cracked.

Because I realized the lie wasn’t only in textbooks. It was in my posture. In the part of me that still wanted to believe the system would treat this like a five-alarm fire. In the part of me that still wanted to believe the rules were the rules, no matter who broke them.

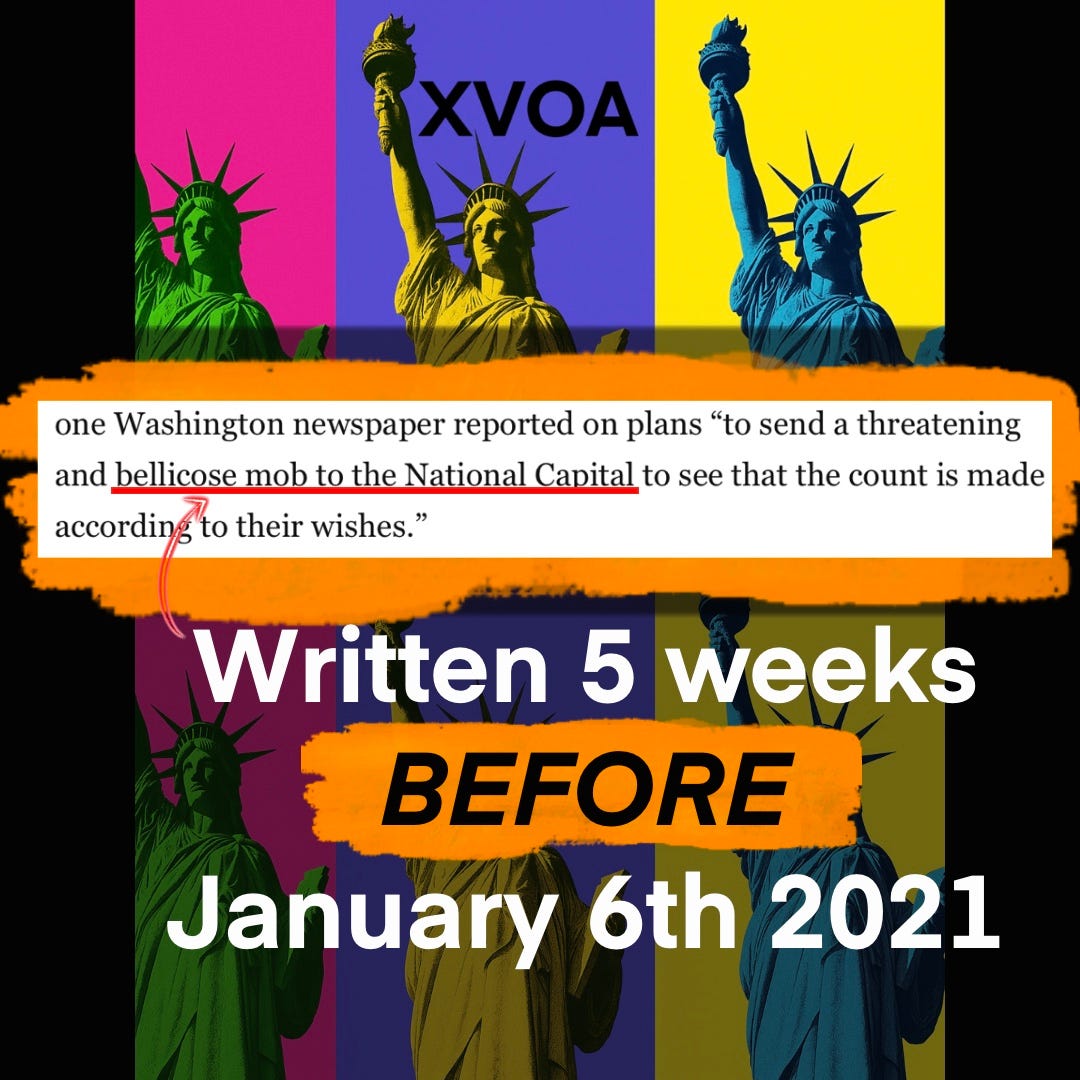

Two months earlier, on November 24, 2020, the Washington Post published a piece by Ronald G. Shafer about the contested presidential election of 1876. In it, Shafer quotes a newspaper describing plans “to send a threatening and bellicose mob to the National Capital to see that the count is made according to their wishes.”

That line didn’t just chill me. It pissed me off. Because it meant America had already run this play, wrote it down, filed it away as “history,” and still acted surprised when the crowd showed up to grab the steering wheel.

So here’s what changed. I didn’t get to keep the polite posture. Sitting there in uniform, hearing that coworker dismiss that crowd like it was weather, I felt my stomach drop and my jaw lock.

I had no choice but to stop believing the system would treat this like a five-alarm fire.

I had no choice but to stop trusting the rules were the rules, no matter who broke them.

I had no choice but to stop pretending that it don’t hurt now.

And that’s what this essay is: the work I couldn’t dodge.

So let’s get to it.

TLDR (because y’all asked)

A bunch of you asked me to make this easier to follow before you commit to the full read. Fair. Here is the short version.

This Washington Post piece about 1876 contains a line about sending a “threatening and bellicose mob” to Washington to force the count. It was published on November 24, 2020. Two months later we watched a mob do exactly that on January 6, 2021.

So I take Shafer’s article and I walk it down, paragraph by paragraph. I match each step to what actually happened from the 2020 election to January 6, and then to the 2025 aftermath, with dates and receipts.

If that sentence grabbed you by the throat, keep reading. The whole essay is built to show you the mechanism, not just the moment.

What follows is a paragraph-by-paragraph breakdown of Shafer’s article. I’m going to match his 1876 mechanics to what we’ve lived through since Trump entered politics, with dates and receipts, because the eeriness isn’t a vibe. It’s structure.

And this is where I want to gently, but firmly, challenge a fellow Substacker I respect, Steward Beckham , when he frames January 6 as something fundamentally new. He writes the following:

January 6 was not the day democracy died. It was the day probabilistic political violence became normalized at the elite level of American life as deniable, repeatable, and survivable for those who flirt with it.

If that sounds dramatic, here is the blunt rebuttal. This is not new. In 1876, elite actors were already talking about using a “threatening and bellicose mob” in Washington to force the count, and the system moved forward anyway. Congress built a workaround, then the settlement rewarded the terror by withdrawing protection from Black citizens. The men who carried it out later bragged about killing, intimidation, and stuffing ballot boxes on the Senate floor. That is political violence treated as a negotiable instrument. January 6 did not invent it. January 6 reminded us that we have been calling it “unthinkable” for so long that we stopped recognizing it as a method.

The point is not to claim magic. The point is to show the mechanism and how the same American sequence keeps reappearing under different costumes.

Who is Shafer, and why did he sound like a fortune teller?

Ronald G. Shafer is a veteran Washington Post journalist and editor who often writes historically grounded pieces that connect past political crises to present anxieties. That craft of using history as a mirror can look like prophecy when the reader has been trained to treat the past as dead.

He wasn’t “spot on” because he guessed the future. He was spot on because he described a recurring American structure: contested legitimacy migrating from voters to procedure, from procedure to pressure, and from pressure to a settlement that restores “order” while quietly changing whose rights get defended.

If you want the spine of this whole essay, it’s this.

When legitimacy is threatened, America reaches for an old sequence.

Crisis → Pressure → Procedure → Settlement → Aftermath.

Shafer names the sequence. January 6 acted it out.

The Exhibit

The Washington Post article is not a supporting citation in the background. It is the exhibit. We are going to walk through it in order, tying each move to what actually happened in the Trump era, with dates.

If you’re still here after that diagram, you’re the reader I’m writing for. The polite version of history tells you January 6 was an “anomaly” and that we can move on. This piece is me refusing to move on until the mechanism is named. If you want to support the work now so I can keep digging, documenting, and writing like this, become a paid subscriber here:

Paragraph-by-paragraph breakdown: the 1876 mechanism and the modern rhyme

1) Election-night disbelief and elite exhaustion

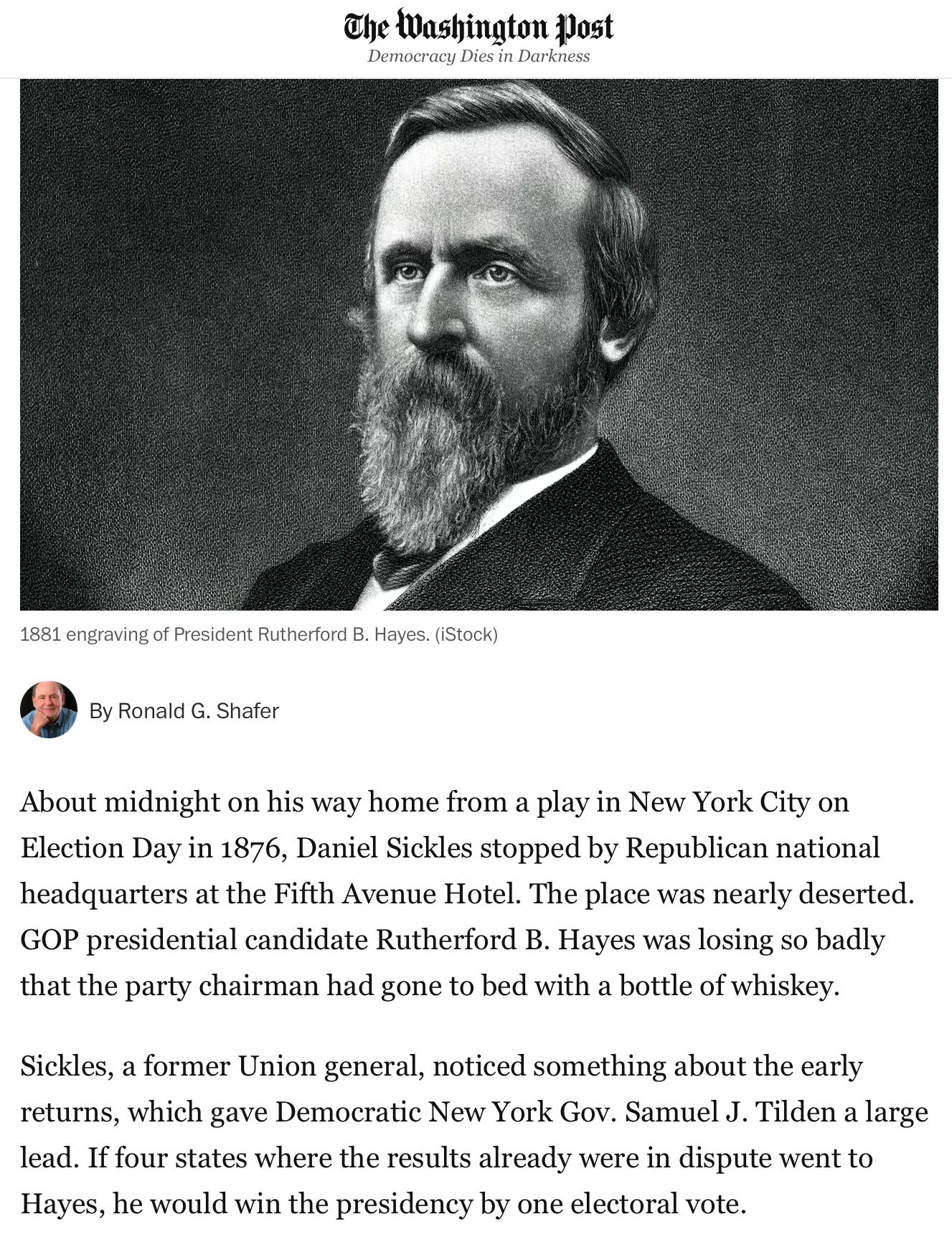

Shafer begins with Daniel Sickles stopping by Republican headquarters on Election Day 1876 and finding the place nearly deserted, with the party chairman reportedly asleep after drinking. In Shafer’s framing, legitimacy crises begin in a fog. The people who are supposed to manage the system are stunned, tired, and unsure what they’re looking at.

That emotional fog rhymes with the 2020 election week. On November 3–7, 2020, the count unfolded over days. Before the race was called, Donald Trump publicly claimed victory and framed continued counting as suspicious. When a population is emotionally primed for betrayal, confusion doesn’t produce patience. It produces certainty. And certainty becomes fuel.

2) The choke-point map

Sickles notices something the sleepy room missed. If four disputed states go the other way, Hayes wins by one electoral vote. That’s the first mechanical insight of the piece: close elections collapse into choke points. The fight stops being national and becomes a battle over a few gates.

That is the 2020–21 rhyme in a single sentence. The procedural fight concentrated on a small number of states and a small number of officials, because those were the gates. You don’t have to convince the whole country when you think you can jam the hinge.

3) “Hold your state”: pressure aimed at the machinery

Sickles sends telegrams urging leaders in contested states to “hold” and “safeguard” Hayes’s votes. The language is almost modern. It treats election administration as a defensive operation and casts the other side as thieves.

The 2020–21 version of “hold your state” is documented in a sequence of pressure moves aimed at state officials and legislatures.

On November 19, 2020, the Associated Press reported that Trump invited the top Republican leaders of Michigan’s legislature to the White House for an extraordinary meeting. They met on November 20, 2020, the same day Georgia certified Biden’s win.

In Pennsylvania, on November 25, 2020, Trump phoned into a meeting of Republican state lawmakers.

On December 7–8, 2020, the Washington Post reported that Trump called Pennsylvania House Speaker Bryan Cutler twice to request help reversing his loss in the state.

You can argue about intent all day, but the structure is clear. Pressure migrated away from voters and toward the machinery that certifies reality.

4) “The election was being stolen”: the ancient story with a modern megaphone

Shafer explicitly draws a modern parallel. Hayes’s backers charged the election was being stolen, “much as President Trump is doing now.” Shafer also makes a distinction: unlike 2020, 1876 involved clear evidence of fraud and voter intimidation.

That contrast matters, because it highlights the psychological function of the stolen-election claim. In 1876, intimidation and fraud were braided into racial terror. In 2020, the stolen-election story operated as a moral permission structure. It didn’t need to be true to be useful. It needed to be believed.

5) Competing realities in the press

Shafer shows Democratic newspapers declaring victory and Republican-aligned outlets insisting the results were uncertain. This is how legitimacy fractures. People stop sharing the same reality.

In 2020, this fracturing didn’t happen over days. It happened over minutes online. By mid-November 2020, “Stop the Steal” had become a public banner. The story wasn’t simply “we lost,” it was “they took it.” Once that narrative sets, the public doesn’t wait for process. The public demands outcome.

6) The principal isn’t always the engine

Shafer notes Hayes’s pessimism even as his allies maneuver. The leader becomes a figurehead for a larger machine.

That is part of the January 6 rhyme. By late 2020, the movement’s emotional engine had its own momentum. The leader becomes both conductor and passenger.

7) The popular vote versus the system

Shafer lays out the numbers. Tilden wins the popular vote by a large margin but falls one electoral vote short; Hayes trails but remains within a procedural path to victory.

That tension between “what people think happened” and “what the system can be made to certify” is not theoretical. It has become a permanent American stress fracture. When a system repeatedly generates legitimacy disputes, factions start treating the rules not as neutral but as weapons.

8) Black voters are the center of the fight

Shafer shifts to what most Americans never learned cleanly. The disputed 1876 states were sites of intense intimidation of Black Republican voters, in a post Civil War atmosphere where Southern whites were rebelling against Black political power. President Ulysses S. Grant sent federal troops to help keep the peace.

The modern rhyme is not identical in form, but it is identical in function. Intimidation shifts who participates and who administers. In the contemporary era, one of the clearest echoes is the sustained harassment of election workers and administrators after 2020.

9) Paramilitary politics as electoral strategy

Shafer details the “Red Shirts” and rifle clubs in South Carolina, including the Hamburg massacre and explicit threats to kill the sitting Republican governor. This is political violence functioning as election strategy.

The rhyme is that January 6 was not random chaos. It was mass pressure aimed at a constitutional ritual, surrounded by organized groups and coordinated narratives that framed violence as patriotic necessity.

10) The voting place becomes a stage of coercion

Shafer describes armed men controlling access to ballot boxes, using horses and bodies to dominate space, cursing and threatening Black voters. Democracy becomes a gauntlet.

The modern rhyme is what happens when voting becomes costly through engineered friction and intimidation. Lines, confusion, fear, and harassment do not need to literally block the window to shape the electorate. They only need to raise the price of participation.

11) Fraud exists, and it is tied to control, not mere cheating

Shafer notes fraud on both sides, including “repeaters” and fraudulent ballots designed to trick illiterate Black voters. The deeper reality is that fraud and intimidation were means to the same end: control of Black political power.

In the modern era, “fraud” became a story so dominant that it justified procedural aggression. It also became the moral cover for policies and executive actions aimed at “election integrity,” even when those actions burdened legitimate voters and election officials.

12) Absurd numbers expose institutional rot

Shafer cites a national turnout of 81.8% and an official South Carolina turnout of 101%, a mathematical confession that the system is corrupt.

The rhyme is that when trust collapses, numbers become symbols. In the modern era, statistical claims, often stripped of context, became viral “proof” in the information war. The argument isn’t really about data. It’s about belonging. Who counts.

13) The operatives are often scandal-soaked and theatrical

Shafer detours into Sickles’ notorious murder trial and the “temporary insanity” defense. It’s a reminder that crisis politics is often driven by dramatic agents, not serene statesmen.

The modern rhyme is obvious. The post-2020 period elevated a cast of operatives who treated the legitimacy fight like a performance. The stage was the republic.

14) Dueling certificates: legitimacy becomes paperwork

Shafer explains the decisive mechanism. When official results were sent to Washington, contested states submitted separate tallies, dueling documents claiming legitimacy.

The modern rhyme has a date: December 14, 2020. That was the day the legitimate electors met in every state and the District of Columbia and cast votes. It was also the day “alternate” slates convened in seven states won by Biden (Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania) to sign false certificates purporting to be the duly chosen electors. The National Archives has since published the unofficial certificates it received in connection with the 2020 election.

This is where the 1876 rhyme stops being metaphor. It becomes procedural reenactment.

15) A patch under pressure: the commission

Shafer notes that Republicans controlled the Senate while Democrats controlled the House, so Congress created an Electoral Commission. By an 8–7 vote, it awarded all disputed electoral votes to Hayes.

The modern rhyme is what happened after January 6 forced Congress to confront how vulnerable the count process was to manipulation. On December 29, 2022, President Biden signed the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022 into law, tightening key rules around the counting process.

A system that has to patch itself after violence is admitting something important. The ritual was vulnerable.

16) The sentence that reads like January 6

Then Shafer quotes the line that haunts this entire essay: a plan to send “a threatening and bellicose mob to the National Capital” to make sure the count is made according to the mob’s wishes.

January 6, 2021 is the rhyme made literal. The crowd’s target was the certification of electoral votes, the count. The Capitol wasn’t a symbol. It was the place where the count becomes real.

17) Dawn legitimacy

Shafer notes that Congress didn’t resolve the 1876 election until March 2, 1877, with a formal announcement at 4:10 a.m. after heated debate.

The modern rhyme is that Congress certified Biden’s win in the early hours of January 7, 2021. Vice President Mike Pence announced just after 3:40 a.m. that Biden had won after Congress completed the counting.

When a ritual is attacked, institutions often respond by finishing it anyway, because finishing it is how they reclaim authority.

18) Continuity first, performance second

Hayes was sworn in privately on March 3 and publicly inaugurated on March 5.

That split has a modern logic: secure continuity first, then perform normalcy. After crisis, the state stabilizes itself before it narrates stability.

19) “His Fraudulency”: the legitimacy wound that doesn’t close

Tilden insisted he was legally elected; dissenters branded Hayes with a mocking title.

The modern rhyme is the long-term damage of a stolen-election story. It doesn’t fade when the calendar flips. It becomes identity.

20) The backroom deal and the withdrawal

Shafer describes historians’ belief that Republicans made a deal at Wormley’s Hotel, and Hayes signaled “home rule” and soon withdrew federal troops from the South.

This is where the Noble Lie does its most destructive work. The polite version calls it reconciliation. The honest version calls it abandonment.

Once federal troops withdrew, the protective capacity of the federal government collapsed in practice. It wasn’t only a moral surrender; it was an operational surrender.

21) The true aftermath: rights devastated

Shafer states it plainly. Black rights were devastated; white rule prevailed; Jim Crow followed.

This is where the modern framing must be anchored. The most dangerous part of a legitimacy crisis is not only the dramatic day. It is what the country becomes afterward, what enforcement is withdrawn, what protections are reinterpreted, what rights become optional.

Trump’s second term supplies concrete dates for that rhyme.

On January 20, 2025, the White House issued a proclamation granting pardons and commutations for certain offenses relating to January 6, 2021. Reporting described the action as roughly 1,500 pardons.

On January 20, 2025, Trump also issued an executive order titled “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship.” The order sought to restrict birthright citizenship and triggered immediate litigation.

On June 27, 2025, the Supreme Court issued an opinion in Trump v. CASA, Inc., arising from challenges to that birthright citizenship order and addressing nationwide injunctions.

On December 5, 2025, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the Trump administration’s challenge to rulings blocking the order.

Also on January 21, 2025, Trump issued an executive order titled “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity,” which revoked Executive Order 11246, a Johnson-era requirement that federal contractors take affirmative action.

On March 25, 2025, Trump issued an executive order titled “Preserving and Protecting the Integrity of American Elections.” The Brennan Center described the elections order as an attempt to overhaul and take control of major parts of the nation’s election systems.

On July 23, 2025, Reuters reported that the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division had lost hundreds of employees since Trump took office, describing a mass exodus tied to a shift away from the division’s historical mission.

The point isn’t that 2025 equals 1877. The point is the rhyme: a legitimacy rupture, followed by acts that normalize the rupture and then re-fight Reconstruction-era constitutional terrain.

22) Tillman’s confession: the mask comes off

Shafer ends with Ben Tillman’s later boast on the Senate floor: “We shot them. We killed them. We stuffed ballot boxes… I do not ask anybody to apologize for it. I am only explaining why we did it.”

That ending is not simply historical trivia. It is the final stage of the sequence. When impunity settles in, power stops denying. It starts justifying.

You can feel the modern echo in the language of “reconciliation” used to describe sweeping January 6 pardons, and in the way official acts and executive orders are used to recast what the country witnessed. Confession becomes a dominance display. The state signals what it will forgive.

The Twilight Zone feeling is institutional, not mystical

If Shafer’s piece feels like prophecy, it’s because our institutions have muscle memory. When legitimacy is threatened, the conflict migrates from persuasion to procedure, from procedure to pressure, and from pressure to settlement. Then the aftermath arrives, not always with fireworks, but with capacity changes, enforcement withdrawals, and constitutional terrain turned into a battlefield.

And I can’t ignore the media layer of it. A piece this blunt, this historically literate, this willing to say the quiet part out loud, feels like the kind of fearless on-the-nose work that would not be tolerated in the new Washington Post climate. The paper reads like it’s managed by Post it notes that just happen to float down from Bezos’s orbit. The vibe is unmistakable. When a newsroom starts acting allergic to its own courage, history stops being a warning system and turns back into polite conversation.

That is why the Noble Lie matters. The polite version of history teaches Americans that we move forward by default. The truthful version shows that rights are defended by force, by law, by enforcement, and sometimes abandoned by deal.

If you only remember January 6 as a day of chaos, you miss the deeper rhyme. The deeper rhyme is what comes after the chaos.

History doesn’t repeat. It rhymes so clean it feels like déjà vu. The question is whether we will keep treating it like polite conversation, or finally start reading it like the warning it has always been.

What I am offering you here is not a hot take. It’s a case file. I’m connecting my own January 6 moment, in uniform, watching the Capitol from miles away, to a nineteenth-century script written in blood. Ben Tillman’s Red Shirt terror was not an accident in the footnotes. It was a method. Lincoln tried to birth a more honest republic. Jefferson wrote liberty while keeping human beings in chains. Obama stood as proof that the story could change, and the backlash proved how badly some people needed it not to.

So here is the ask. If this piece tightened something in your chest, do not just nod and scroll. Restack it. Send it to the one friend who still thinks January 6 was just a “bad day.” Share it because the polite version of history is killing us. And if you want me to keep digging with receipts, dates, and names, not vibes, become a paid subscriber. That is how you fund the work it takes to tell the truth when the truth is inconvenient as hell.

Sources (plain links)

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/11/24/rutherford-hayes-fraud-election-trump/

https://apnews.com/article/trump-invites-michigan-gop-white-house-6ab95edd3373ecc9607381175d6f3328

https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/dialing-pa-gop-meeting-president-trump-shows-sign/story?id=74405323

https://www.c-span.org/program/campaign-2020/pennsylvania-republican-hearing-on-2020-election/557122

https://www.archives.gov/foia/2020-presidential-election-unofficial-certificates

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4573

https://www.cbsnews.com/live-updates/electoral-college-vote-count-biden-victory/

Another excellent and informative post. This is HCR-level comparative analysis. Well done. As happens with almost every HCR Letter, I learned some new things today.

Very interesting to see that pattern across history. Thanks for your clear and digestible way of sharing.