Why America Only Finds Its Outrage When the Fraudster Has a Muslim Name

How NYT and WaPo racialize theft, sanitize white-collar fraud and protect the system that keeps printing scams.

This is me, yours truly Xplisset, putting two very different pieces of “serious journalism” on the table and asking a simple question: who do they quietly train you to blame

On one side, you’ve got a New York Times news story about pandemic-era fraud in Minnesota’s social services system. On the other, a Washington Post opinion column titled “Welfare fraud is far too common.” Same state, same prosecutor, overlapping facts. But once you look at the headlines, the photos and the first few sentences, you can see two elite outlets doing the same trick in different accents: turning real fraud into a story about Somalis, “those people,” and a Democrat governor, while the system that built the scam quietly slips out the back door.

What follows is not a defense of fraudsters. It’s a close read of how print vs. digital headlines, news vs. opinion, and that very official-looking prosecutor photo work together to racialize theft, protect power and make sure “welfare fraud” never conjures up the people who actually designed the programs.

The first thing that grabbed me wasn’t the headline. It was that photo. The very official looking prosecutors.

You’ve got the U.S. attorney at the podium, flanked by a row of very serious men who look like they’re about to drop the teaser trailer for a new prestige drama called Law & Order: Medicaid Unit. Cameras in the foreground, flags in the background, everybody in the same suit uniform. It’s the visual language of “grown-ups in charge.” Before you read a single word, your brain already knows who the heroes are supposed to be and who “the problem” is going to be. Spoiler: it’s not the guys in the suits.

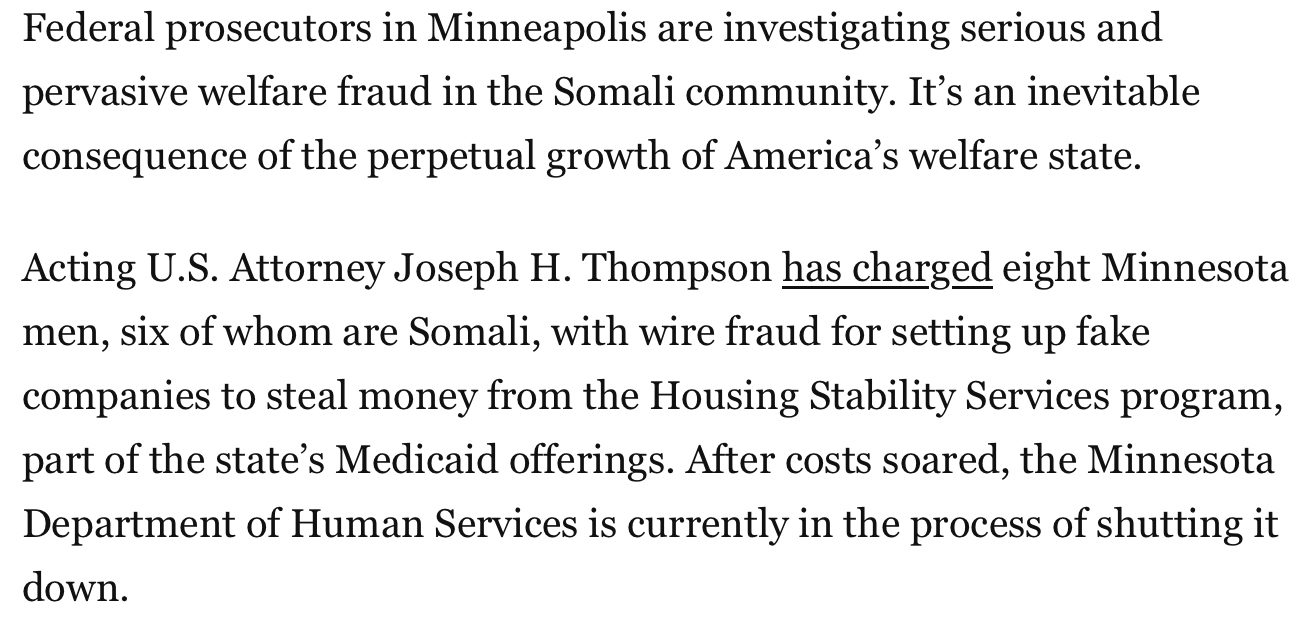

Then you get the online headline: “How Fraud Swamped Minnesota’s Social Services System on Tim Walz’s Watch.” Inside the story, the words “Somali diaspora” and “growing political power” show up early and often. Over at the Washington Post, the op-ed version comes in even hotter.

The piece is titled “Welfare fraud is far too common,” which sounds bland and policy-ish until you hit the very first sentence: prosecutors chasing “serious and pervasive welfare fraud in the Somali community” as “an inevitable consequence of the perpetual growth of America’s welfare state.” Same state, same prosecutor, same rough set of facts, but the frame is already leaning on Somalis and the “welfare state” before you’ve even finished the first breath.

I’ll own this: the first time I saw “Somali” and “welfare fraud” in the same graf, some old stereotypes I thought I had retired stirred in my own nervous system. That’s the part that bothers me most. It means the headlines aren’t just manipulating “other people.” They’re playing an instrument that lives in me too.

If you actually read the Times piece all the way through, you can see the reporter trying to walk the tightrope. He gives you numbers, timelines, how the schemes worked, who got charged. He quotes Somali community members who are furious at what was done in their name. He even acknowledges the atmosphere after George Floyd’s murder and how fear of being called racist made regulators hesitate. That’s real complexity.

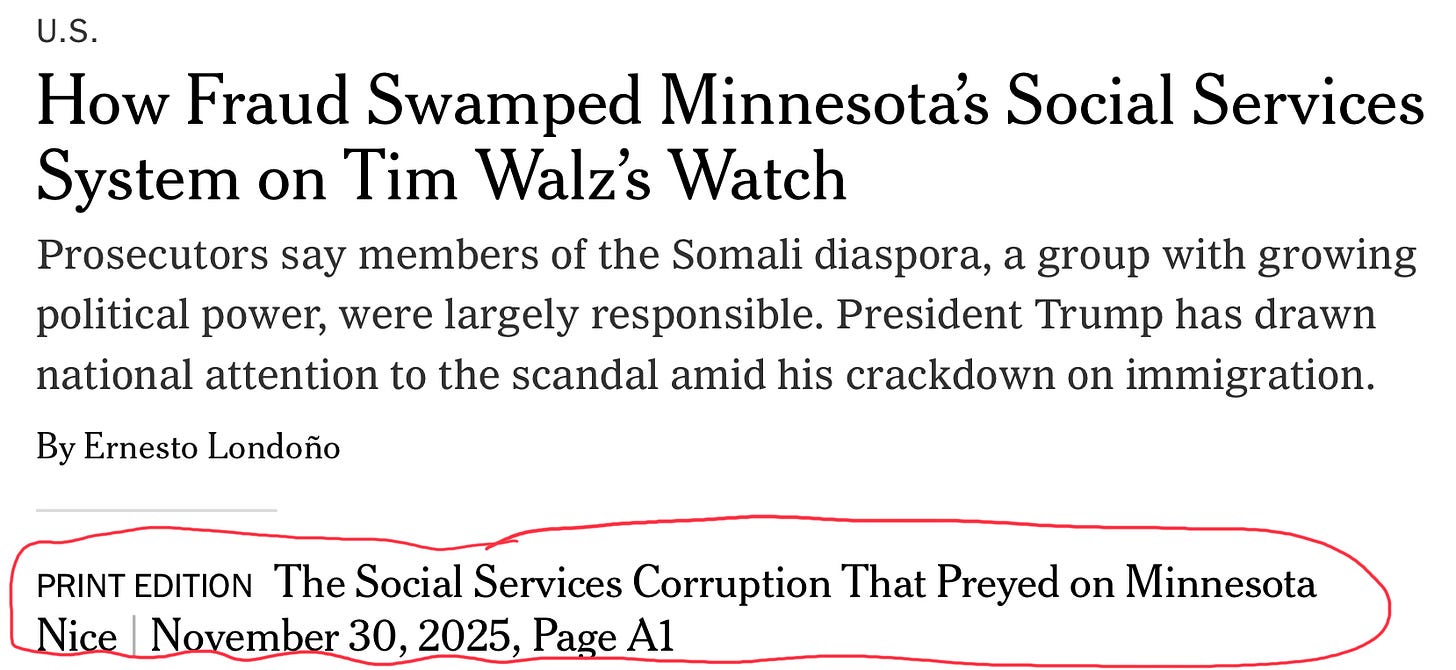

Now here’s where it gets interesting. In print, the same story ran under a very different headline: “The Social Services Corruption That Preyed on Minnesota Nice.” That’s vibes ya’ll, not villains. It’s written for the older print reader sipping coffee at the kitchen table, leaning into mood and theme: a generous state, a cherished identity, something precious being taken advantage of. Nobody’s name in lights, no specific community in the crosshairs. But the digital version trims off “Minnesota Nice” and slaps in “on Tim Walz’s watch,” then layers “Somali diaspora” and Trump’s immigration crackdown into the opening. Same article, two different masks: one for a broad, local-ish audience that still thinks of the paper as a civic institution, one for the algorithm that rewards named enemies and hot-button nouns.

Framing

But then look at how the story is framed once you’re inside. The online headline drags Tim Walz into the title even though he’s one actor in a much bigger machine. “On Tim Walz’s watch” is doing a lot of emotional work. It tells you, before you get any detail, that this is a story about a feckless Democrat who let “those people” loot the pantry. The early emphasis on “Somali diaspora” plus “growing political power” invites you to read the whole scandal as a morality play about ungrateful newcomers and soft-headed progressives who were too scared of being called racist to enforce the rules.

Slide over to the Post op-ed and the mask basically comes off. No tortured paragraphs about “Minnesota Nice.” No wrestling with the fact that most Somalis are just living their lives and paying taxes. The column opens with “serious and pervasive welfare fraud in the Somali community” and within a breath we’re at “inevitable consequence of the perpetual growth of America’s welfare state.” That’s not analysis, that’s a closing argument the writer had in the drawer before Minnesota ever cut the first check.

Notice what both pieces have in common.

You could play a drinking game around the word “Somali” in either one and end up on the floor before you hit the middle. Both make sure to add the required “obviously most Somali immigrants aren’t criminals,” the op-ed equivalent of “no offense, but.” Both nod to a City Journal rumor about money going to Al Shabab, even while admitting there’s no hard evidence, just enough to keep the terror cloud hanging over the reader’s head. Plant the seed, then remind us it hasn’t technically sprouted.

And both manage, in different ways, to protect the system that made this fraud possible.

In the Times story, Minnesota is framed as almost innocent in its own disaster. A generous Scandinavian-modeled safety net “susceptible” to exploitation. Agencies “overwhelmed.” Officials perhaps a bit too trusting. The quote elevated as the moral center is a federal prosecutor lamenting, “We’re losing our way of life in Minnesota.” The tragedy is not that hungry kids didn’t eat. It’s that an ideal of “Minnesota Nice” got violated.

In the Post op-ed, the villain isn’t just the Somali scammers, it’s the idea of robust social services itself. The author walks you through big improper-payment numbers and then shrugs in the direction of conservatives, who “assume government money will probably be wasted anyway.” The quiet subtext: if you build a welfare state, don’t be surprised when brown people steal from it. There’s no serious discussion of how programs are designed, what oversight was cut, which lawmakers preferred speed over verification, or who benefits from running money through private intermediaries. The pipes are invisible. Only the people drinking from them are vivid.

Meanwhile, Trump takes the whole storyline and turns it into policy theater. He uses the Minnesota cases to justify ending Temporary Protected Status for Somalis, which barely touches the people actually involved and does real damage to folks who have nothing to do with this mess. TPS is tiny; the fraud numbers are huge. The policy move doesn’t match the alleged problem at all. It does match the picture he wants his base to see: Black Muslim faces as the embodiment of “welfare fraud.”

The Term “Welfare Fraud”

This is where the wannabe psychologist in me starts tapping the table. In a country that routinely shrugs at corporate tax tricks, defense contractors “losing” billions, and banks paying fines that are a fraction of what they stole, why does “welfare fraud” land in the gut so much harder? Why does a Somali woman running a fake daycare feel more scandalous than a consulting firm billing the government $600 an hour to do very little? It’s because we’ve built a national self-image that says we are generous and fair, and then we dump the shadow of greed, laziness and entitlement onto whoever is standing at the benefits office window.

Yesterday it was “welfare queens” with Black American names. Today it’s Somali Minnesotans with Muslim ones. Tomorrow it will be whatever group is most convenient when the next scandal breaks. The pattern is the same: individual bad actors do something real and harmful, and instead of aiming outrage at the architecture that made it easy, we let headlines turn the whole community into the villain of the week.

Witch Hunt?

I really really wanted this to be a pure witch hunt story, with no real fraud at all, because that would make it cleaner emotionally. The harder truth is that some of these folks did exactly what the indictments say. They stole money meant for hungry kids and people on the edge of homelessness. They bought houses and cars and lived large. That is ugly and deserves consequences. My story no longer fits the facts if I pretend the only thieves are wearing cufflinks and lanyards.

But acknowledging real crime does not require swallowing the way these outlets load the dice. The question isn’t, “Did fraud happen?” It’s, whose name gets welded to the crime, and whose design decisions get treated like unfortunate background noise. You could headline this as a story about a state that built wide-open programs and didn’t invest in oversight. You could focus on agencies that kept refilling the cookie jar while the crumbs piled up on the floor. Instead, we get titles and photos that tell us, from the first scroll, who should be ashamed. Hint: it ain’t the row of men in matching suits under the eagle seal.

Try This

If you’ve made it to the end, try a small experiment with me. Next time you see the phrase “welfare fraud” in a headline, pause before clicking. Check who your imagination has already cast in the lead role. Whose face shows up? Who gets to be the nameless “system,” and who is the named problem child? That reaction is not just your private bias. It’s the residue of years of stories just like these, teaching us whose theft is a scandal and whose theft is a line item.

Name the small cost in your own story. Maybe it’s the time you nodded along to a headline without noticing how neatly it fit your fears. Maybe it’s the joke you let slide about “those people and welfare.” I’m not standing outside this either; I’m in the frame. The good news is once you catch the trick, you can stop letting other people cast you in their little morality play about who deserves help and who deserves suspicion.

And if this piece helped you see the trick a little clearer, here’s the part where I ask for something back. A few weeks ago I wrote a post titled “WashPost Put Dr. Heather Cox Richardson’s Face On It, Then Erased Her Name.” Y’all pushed it so hard it went genuinely viral. I would bet good money that somebody in the Post newsroom had it dropped into their inbox with a subject line that started, “Have you seen this?” That didn’t happen because I have a fancy masthead. It happened because a tiny army of readers decided one retired cop with a laptop should be in conversation with the people who shape the narrative.

Every paid subscription you give me isn’t just a tip jar. It buys me hours. Hours to pull PDFs, line up coverage from different outlets, read the boring legislative audits, and then translate all of that into something that hits you in the gut and lands in the inboxes of the very institutions I’m critiquing. If you want more pieces that walk straight into the belly of the beast and say, “We see what you’re doing with our stories,” that’s what your support funds.

If you’re in a position to do it, you can start a paid subscription here:

It keeps this work independent, a little bit dangerous, and very much yours.

Thanks, Xavier. It's maddening that the fraud they complain about is miniscule. I used to be a case manager, and the last I read about benefits fraud, it was something around 3%. And most of the Medicaid fraud is committed by health providers and capital equipment rental companies. It's not the patients who are committing it.

I’m new to your work. I appreciate your analysis and clarity. I especially appreciate how you expose and explain our bias and own your own when you feel it. Thank-you.