Why Did We Take Maduro?

The Petrodollar Theory and the Real Math Behind The Intervention In Venezuela

Introduction

I’m going to start this the way I used to start a report when everybody in the room already had their favorite suspect.

When something big happens, especially something loud and cinematic, everybody suddenly knows why. They don’t just have a theory. They have certainty. And if there’s one thing I learned wearing a badge as a patrol officer, it’s that certainty is often the first thing that shows up at the scene, and just so happens to be the last thing that survives the evidence.

So I’m putting on my old cop writing persona for this one: just the facts, as cleanly as I can manage them, even when the facts are inconvenient to my own instincts. And I’m doing it at the risk of a few flashbacks: reports tossed back at me with red correction marks (yes, we were still writing on paper in my rookie years), like I’d wandered back into middle-school English. I’m not here to perform a conclusion. I’m here to earn one.

I’m also unabashedly borrowing a lesson from Dave Chappelle’s latest Netflix special, the one where he spends real time (funny time, but real time) trying to explain why he took a Saudi-funded payday to perform in Riyadh. I’m paraphrasing the takeaway, not quoting it: anybody who tells you they already have the whole answer and it wraps up neatly as a conspiracy is usually advertising they haven’t done the homework.

Funny thing: one comedian takes a Saudi check and has to do a whole segment explaining it. Meanwhile, the world’s been taking the bigger version of that check for decades. Only ours comes disguised as “energy markets,” settled in dollars, and stapled to Treasury auctions. We call it “stability.”

So here’s my honest starting position: I don’t know the answer. But I can tell you this much: if you want to evaluate the “petrodollar” explanation for Venezuela without fooling yourself, you have to do two things at once.

Follow the money and the settlement system (what currency oil gets priced in, and why that matters).

Follow the chemistry and the infrastructure (what kind of oil the U.S. can actually run through its refineries, and what Venezuela uniquely has). [8]

That’s what this essay does.

The petrodollar theory posits that the United States has a structural incentive to intervene in oil-rich countries to protect the dollar’s dominance in energy trade. In the case of Venezuela, home to the world’s largest proven oil reserves, some argue that U.S. actions (sanctions, pressure campaigns, and direct intervention) are best explained by threats to the petrodollar system rather than solely by concerns about democracy or human rights.

What follows is a critical analysis of that claim. We compare Venezuela’s case with key historical precedents: Iran’s Mossadegh (1953), Iraq (2003), and Libya (2011). We also incorporate the technical oil-market dynamics that tend to get lost in currency-only debates (including the refinery mismatch and the strategic value of the Orinoco Belt). [8] The goal is simple: test the petrodollar theory as a framework, where it holds, where it overreaches, and what the evidence can actually support.

TLDR

A few folks asked for a short version. Fair. Here it is. Not a spoiler. More like a trailer.

If you came for a clean conspiracy with one villain and one motive, you might leave annoyed. The evidence behaves messier than that.

This essay tests the petrodollar story using two lenses at the same time: currency plumbing (what oil is priced in and who controls settlement) and refinery chemistry (what kind of crude the U.S. can actually run). [2] [8]

The hinge is 1971. Nixon shuts the gold window. The dollar needs a different kind of anchor. [15] [18]

Venezuela matters because it sits where the marriage gets tested: Orinoco heavy crude that Gulf Coast refineries were built to digest, plus a world experimenting with non-dollar settlement. [8] [12]

If you only read one section, read “The Venezuela Case: Oil, Refining, and the Dollar,” especially the subsection “Heavy Sour Crude vs. U.S. Refinery Needs.” That is where the “petrodollar” argument runs into the physical reality of refineries. That is where this story stops being slogan and starts acting like a motive. [8]

The Petrodollar System: Background and Significance

After World War II, the U.S. dollar became the world’s primary reserve currency, used widely in international trade and finance under the Bretton Woods system. Other currencies were pegged to the dollar, and the dollar was (for foreign governments) convertible into gold at a fixed rate. [17]

That arrangement cracked under the weight of U.S. deficits, Vietnam-era spending, and mounting foreign claims on U.S. gold. [16] On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon closed the “gold window,” ending the dollar’s convertibility into gold for foreign governments. [15] [18] In plain language: the dollar stopped being a claim on a metal and became, more openly, a claim on U.S. state power and U.S. economic capacity. [15]

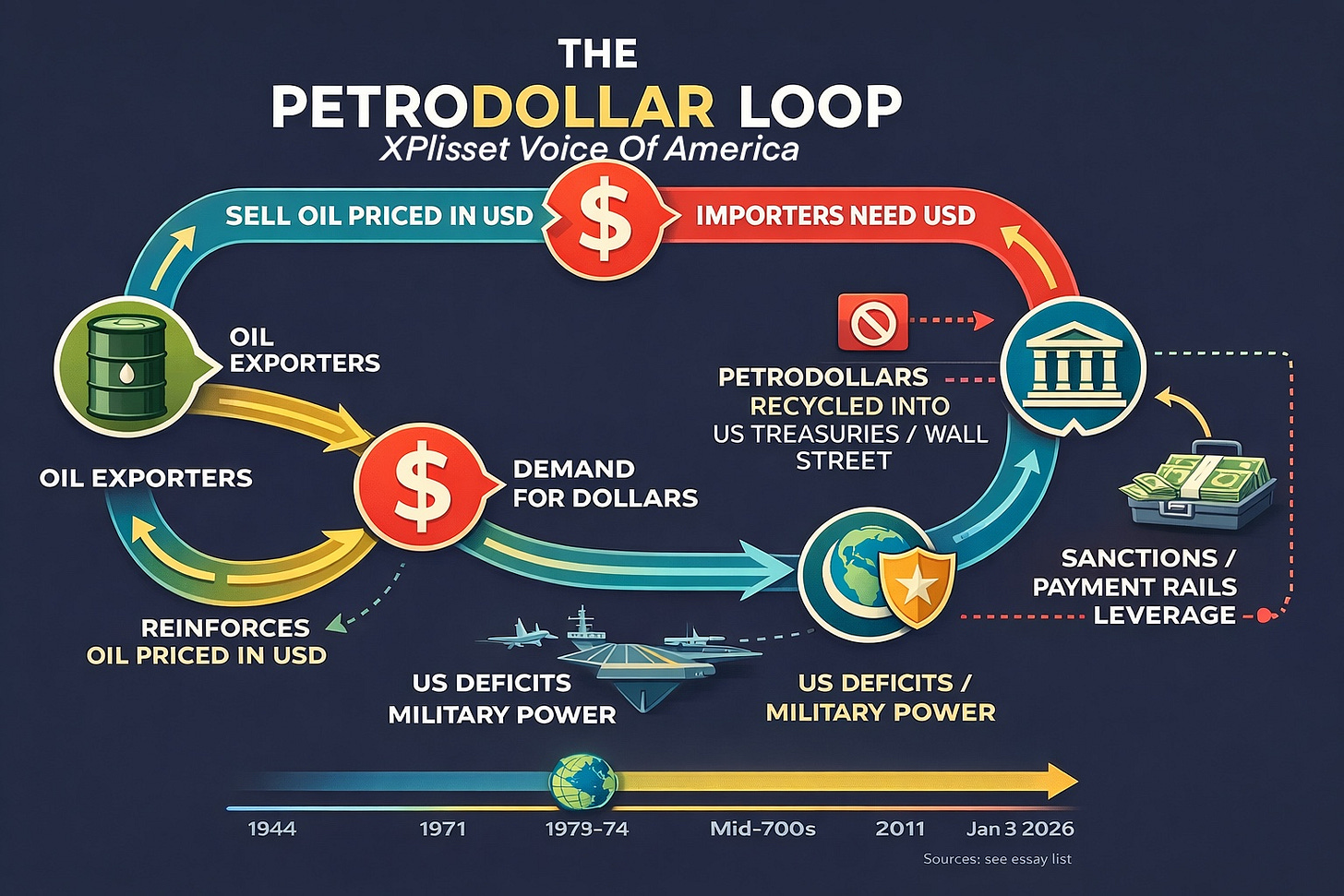

Once the dollar floated, its value could fall. For oil exporters, that meant the dollars they received for crude could buy less on the world market. Then the 1973 to 1974 oil crisis hit, and oil became the world’s most important price signal at the exact moment money lost its old anchor. [2]

Out of that collision emerged a stabilizing bargain that petrodollar proponents always point to. Oil sales would be priced largely in U.S. dollars, and the surplus dollars from those sales would flow back into dollar assets (often U.S. Treasuries and other dollar-denominated instruments). [2] In return, the United States provided security guarantees and strategic partnership, most visibly with Saudi Arabia, the swing producer that could set the tone for global oil trade. [2]

This arrangement is what people mean by the modern petrodollar: oil-importing nations need dollars to buy crude, and oil exporters end up holding and recycling large pools of dollars, strengthening demand for USD and deepening the dollar’s global network effects. [2]

The benefits for the United States are straightforward. Dollar-priced oil reinforces the dollar’s use in global trade. Petrodollar recycling supports demand for U.S. assets. U.S. policymakers gain leverage through the financial plumbing that comes with currency centrality. [2]

Threats to the petrodollar

If major oil producers stop selling oil in dollars, it could erode global demand for the currency and undermine this arrangement. [2] Reduced international demand for dollars could devalue the currency, trigger inflation in the U.S., and even prompt foreign creditors to liquidate dollar reserves or bonds. [2]

However, it’s important to note counterarguments from economists who call the most dramatic versions of these fears overblown. Dean Baker, for example, argues that oil being priced in dollars is largely a convention, and that currency conversion is routine. He treats the grand “dump the dollar” storyline as more legend than economics. [1]

In summary, the idea of the petrodollar’s importance is real, but experts debate how vulnerable the system truly is to one country’s defection. [1] [2]

Midpoint Check In

If you are the kind of reader who has to jump off the train before the last stop, here is the honest ask.

This kind of work is slow on purpose. It is not vibes. It is documents, incentives, and the boring machinery of power that shows up later as your gas price and your grocery bill.

We say we want truth, then we reward the loudest performance. We say we want democracy, then we fund entertainment and act shocked when entertainment wins. That is not a scold. That is the math of attention.

If you want more work like this, deeper and more often, paid support is how I buy the hours to do it. If XVOA is worth one small monthly bill to you, step in here:

If money is tight, no shame. Save it for later. Share this post. Text it to one person who still reads. Either way, you are helping keep the lights on.

Now, back to the evidence.

Historical Parallels: Oil, Currency, and Regime Change

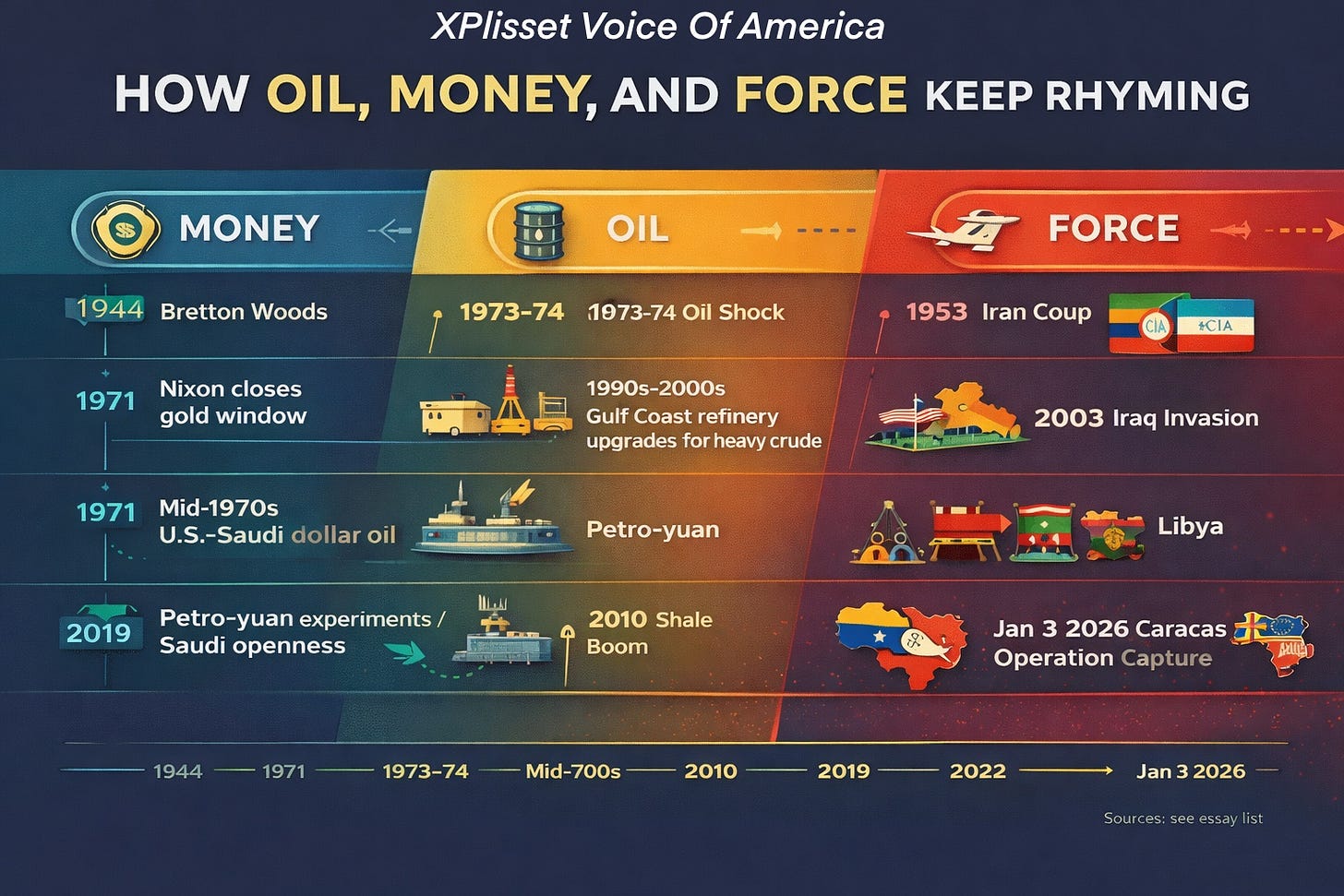

Several oft-cited episodes are frequently raised by proponents of the petrodollar theory. In each case, a country’s leadership either controlled valuable oil resources or threatened to move away from the dollar, and subsequently faced U.S.-backed intervention. We will examine three examples: Iran (1953), Iraq (2003), and Libya (2011).

Iran 1953: Oil Nationalization and the Coup against Mossadegh

In 1951, Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, moved to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), a British-owned firm that had long extracted Iran’s oil while giving only a small share of profits back to Iran. Britain began plotting Mossadegh’s removal almost as soon as nationalization was announced. [7]

The U.S. initially hesitated, but the calculus changed with Cold War fears that a destabilized Iran might drift into the Soviet orbit. In August 1953, the CIA and British intelligence orchestrated a coup (Operation Ajax) that overthrew Mossadegh and consolidated the pro-Western Shah’s rule. [7]

This coup predates the official petrodollar system by two decades, so it wasn’t about dollar pricing per se. But it established the ancestor-pattern: oil sovereignty moves can trigger regime-change pressure when they threaten Western strategic and corporate interests. [7]

Iraq 2003: War, Oil Reserves, and Saddam’s Euro Experiment

Officially, the U.S.-led 2003 invasion of Iraq was justified by claims that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction and by the desire to topple a brutal dictator. No WMD stockpiles were found, and skeptics argued oil was the underlying motive. Former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan later wrote that the Iraq war was “largely about oil.” [4]

Beyond oil volumes, Saddam also made a provocative monetary move. In October 2000, Iraq switched its oil export payments from U.S. dollars to euros, a symbolic rebuke to U.S. power. [3] After the invasion, Iraq’s oil sales were shifted back to dollars. [5]

A sober reading is that the U.S. had long-standing interests in Iraq’s oil and regional positioning regardless of currency. Still, the euro move plausibly reinforced the logic that Iraq was not simply an oil issue. It was also a monetary and sanctions issue. [5]

Libya 2011: Gaddafi’s Gold Dinar and NATO’s Intervention

The NATO intervention in Libya (2011) is sometimes framed through a monetary lens because Muammar Gaddafi advocated African economic independence and toyed with ideas associated with a gold-backed currency. A leaked email discussed French intelligence concerns that Gaddafi’s plans could threaten France’s monetary influence in Africa. [6]

This case is murkier than Iraq. The humanitarian trigger and civil-war dynamics were immediate. Still, Libya shows a broader theme: when oil and monetary influence align, financial motives can ride along with political ones. [6]

Patterns and Caveats

Across these cases, a few threads recur:

Oil remains strategic, not just economic.

Currency and payment systems are now part of power projection.

Public justifications rarely foreground the financial architecture.

But we should avoid monocausal thinking. Each intervention had multiple drivers. Petrodollar logic may be structural background, sometimes decisive, sometimes just reinforcing.

The Venezuela Case: Oil, Refining, and the Dollar

Venezuela presents a contemporary test of the petrodollar theory. Under Hugo Chávez and his successor Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela has been an outspoken anti-U.S. player, aligning with countries like China, Russia, and Iran. Venezuela’s oil riches are colossal, with an estimated 304 billion barrels of reserves, the largest on the planet, largely in the form of heavy crude in the Orinoco Belt. [8]

Quick translation for regular people: the Orinoco Belt (sometimes called the Orinoco Oil Belt or La Faja) is a long, wide strip of land in eastern Venezuela that runs along the Orinoco River. Under that strip sits a massive deposit of extra-heavy oil, thicker than what most people imagine when they think “crude.” It can look more like tar or syrup than the light oil that comes out of many U.S. shale wells. [8] To turn it into usable fuels, it often has to be blended, diluted, or “upgraded” with special processing. [8]

Yet Venezuela’s production has fallen sharply in recent years, making its oil both a prize and a challenge.

Heavy Sour Crude vs. U.S. Refinery Needs

Most of Venezuela’s oil is heavy, sour crude. A big share of that story is the Orinoco Belt you just read about. That’s where the extra-heavy barrels live, the tar-like crude that often has to be diluted or upgraded before it can move and be turned into useful fuel. [8]

This contrasts sharply with the light, sweet crude produced by U.S. shale. Light oil is easier to refine. Heavy crude is harder and leaves more leftover material that requires extra processing. [8]

U.S. Gulf Coast refineries were deliberately built to handle heavy grades. These complex refineries invested billions in cokers, hydrocrackers, and desulfurization units so they could turn cheap heavy crude into high-value products. [8]

U.S. “energy independence” rhetoric in the 2010s glossed over this quality mismatch. The U.S. became a massive producer, but much of that is light oil that U.S. refiners export or must blend, because their systems still crave heavier feedstock. [8]

Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) pressures

From the petrodollar perspective, Venezuela’s heavy oil also intersects with the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). [9] In 2022, the U.S. drained the SPR heavily to combat fuel price spikes. [9] Gas prices are the closest thing America has to a national mood ring: big numbers on bright signs, every day, in every neighborhood. With inflation biting and elections on the calendar, there was enormous pressure on the White House to show fast relief at the pump.

The SPR is one of the only levers a president can pull quickly because you don’t have to wait years for new drilling, new pipelines, or new refineries. Supporters framed the releases as inflation relief and energy security. Critics framed them as a way to buy time and goodwill before voters showed up. [9]

Either way, the tradeoff was real: short-term price relief, long-term vulnerability. [9]

Petrodollar Threats: Venezuela and the Dollar

On the monetary front, Venezuela has taken steps outside the dollar system, especially after U.S. sanctions restricted its access to U.S. financial rails. It accepted payments in other currencies, bartered oil for goods, and attempted the “Petro” cryptocurrency experiment.

By the mid-2020s, the petrodollar system was visibly fraying at the edges globally. Saudi Arabia signaled openness to experimenting with non-dollar settlements, including discussion of “petroyuan.” [12]

From Washington’s perspective, these trends are concerning. If Venezuela, with its massive reserves, were to formalize non-dollar oil pricing, it could add volume and legitimacy to multi-currency oil trade.

U.S. Intervention in Venezuela: Motives and Outcomes

U.S. policy toward Venezuela over the last decade leaned hard on sanctions and diplomacy meant to isolate the Maduro government. “Sanctions” can sound abstract, so here’s what it usually means in real life: limits on who can buy Venezuela’s oil, limits on which banks can move Venezuela’s money, and penalties for companies that do business with Venezuela’s state oil company.

Now, the event that triggers this whole essay happened on Saturday, January 3, 2026: U.S. forces conducted a pre-dawn operation in Caracas and took Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores into custody, transporting them to the United States to face federal drug-related charges. [10] [11]

A few pieces of context matter if you’re trying to understand why this was so fast and why it looked so surgical.

The operation had one narrow objective. It wasn’t framed as an occupation or a regime-change war “for democracy.” The declared objective was capture and removal for prosecution. [10] [11]

Reuters described months of planning and rehearsals. Reuters reported that U.S. forces built a replica of Maduro’s safe house for rehearsals, and that U.S. intelligence tracked Maduro’s routines and movements over months. [10]

Reuters and AP reporting describe the scale and sequencing as designed to limit response. The reporting described strikes on Venezuelan military targets and air defenses followed by rapid insertion and rapid extraction, contributing to a “clean” look from a distance even while violence and disruption were reported locally. [10] [11]

The optics and the law are now part of the battlefield. The reporting describes international arguments over legality, sovereignty, and precedent, and the U.S. framing of the operation around law enforcement charges. [10] [11]

Now, the two YouTube videos used in researching this essay capture the interpretation layer that formed almost instantly:

“The End of the Petrodollar? The Real Reason Behind the Venezuela Raid Revealed.” [13]

“$200 OIL IS HERE: The “ORINOCO BLOCKADE” That No One Is Watching.” [14]

Their core claim is simple: remove the political barrier, then reconnect Venezuela’s oil industry to the dollar pipeline. In plain terms, that would mean restoring contracts priced in dollars, reopening the door for large Western oil companies and service firms, and rebuilding the legal and financial on-ramps that let Venezuelan oil flow into the standard global market instead of the shadow market.

And this is where the Venezuela story turns into an economic Catch-22.

A “clean” decapitation strike can still produce an oil mess if it triggers sabotage, strikes, or a security vacuum around pipelines, ports, and upgraders. [14] If output stalls, the problem isn’t just gasoline. Heavy crude constraints hit diesel and jet fuel in ways light shale oil can’t magically fix. [8] Diesel moves the whole country: trucks, trains, farm equipment, shipping. When diesel gets scarce or expensive, groceries and everyday goods feel it fast.

Think of it like trying to fill a bathtub while somebody keeps messing with the faucet. You can win the bathroom, and still end up with no water.

Conspiracy or Credible Strategy? – Evaluating the Petrodollar Theory

Is the petrodollar theory a valid lens for understanding U.S. actions, or is it an overhyped conspiracy narrative? The evidence suggests a bit of both.

On one hand, numerous historical data points support the notion that the U.S. is sensitive to any threat to the dollar’s central role in global finance, especially in commodities. [2]

On the other hand, calling it a conspiracy implies a single hidden motive that overdetermines events. Real decision-making involves a web of factors: security alliances, ideology, domestic politics, corporate interests, and resource strategy.

Economists who dismiss petrodollar panic emphasize that the dollar’s dominance is reinforced by fundamentals (market depth, legal predictability, liquidity), and that oil-trade currency choice is a relatively small slice of global dollar demand. [1]

Conclusion

In my cop days, the end of a report was always the same ritual. You stop narrating. You summarize what you know, you name what you can’t prove, and you write it in a way that will still make sense when somebody else reads it months later, after the adrenaline has worn off and the stories have gotten louder than the facts.

So here’s what I know.

The petrodollar theory is not magic. It’s not a single secret meeting where somebody slid a napkin across a table and redesigned world history. But it’s also not nothing. After 1971, when the dollar stopped being a claim on gold, the U.S. needed the world to keep needing dollars. [15] Oil priced in dollars, settled in dollars, recycled back into dollar assets became one of the ways that need stayed automatic. [2]

And Venezuela sits right at the intersection where slogans turn into plumbing: a giant pool of heavy crude that the Gulf Coast can actually use, in a world that’s been experimenting (even cautiously) with trading energy outside the dollar. [8] [12]

Now here’s what I can’t prove.

I can’t prove, from public evidence alone, that the petrodollar theory is the reason the United States took Maduro into custody. Foreign policy almost never hands you one motive in a neat envelope. It hands you a stack.

But I can tell you what I’m not willing to pretend anymore: that barrels and balance sheets are irrelevant to “democracy talk.” Not when our entire modern lifestyle is built on cheap fuel moving through a fragile system.

And before I sound like I’m judging anybody from some high horse, let me confess something. I have owned trucks and SUVs myself. I liked the room, the power, the feeling of being wrapped in steel. So no, I am not condemning anybody for driving what fits their life.

I am saying we should be honest about the trade. The most popular form of American “freedom” is a seven-seat SUV and a pickup truck that drinks like it’s getting paid by the gallon, and that kind of freedom comes with a fuel bill that never stays local.

Which brings me back to that Chappelle special.

There’s a moment where he brags that he can tell trans jokes in Saudi Arabia, jokes that would get him canceled back home, and still collect his check and stroll out like nothing happened. The joke lands because it’s true in a narrow way: hegets to leave. He gets to cash the check and catch a flight.

But the part that sticks in my throat is what the joke doesn’t have to carry: trans people in places like that don’t get to treat identity like a bit. They don’t get to “leave the stage” when the set is over. Their freedom is not the punchline. It’s the receipt.

And I can’t shake the feeling that our fuel story works the same way.

We love to talk about freedom like it’s weightless and like it’s just a vibe. But our freedom to floor it down the highway in a thirsty vehicle has always depended on someone else absorbing the costs: sanctions, coups, wars, blown-up infrastructure, and the quiet assumption that some people’s sovereignty is flexible when the refinery math gets tight.

So if you’re asking me whether the petrodollar theory is true, my answer is still the same: I don’t know.

But I do know this: the moment we pretend the oil system is “just economics,” we stop asking the moral question that matters, which is who pays for our version of freedom, and who gets told to shut up so we can keep the tank full.

That’s the patrol officer in me, still trying to write it clean: facts first, ego last, and no conclusions that can’t survive the evidence. But also, no comfort that can’t survive the conscience.

Support This Work

Let me talk plain right here right now.

We keep saying we want democracy. We keep saying we want truth. We keep saying we want accountability. Then we starve the people doing the unglamorous work of reading, checking, revising, and saying, I might be wrong, let me prove it.

We think democracy runs on autopilot. We think truth is going to float to the top like it is lighter than lies. We think the system will correct itself because it always has. Then we act surprised when the loudest microphone wins, when the richest man buys the megaphone, and when the rest of us are left arguing over shadows.

If you made it this far, you already know what this is. This is a little flashlight in a loud room. This is XVOA choosing receipts over vibes, even when the receipt makes me look foolish, because the truth is more important than my ego.

Mainstream media will keep the cameras on the circus. I’m trying to keep my eyes on the bank vault. Sometimes I will miss. When I miss, I will say so. That’s the deal.

Let me say this with a smile and a straight face.

This article did not arrive like some magical DoorDash order, hot and ready, while I sat back waiting for the app to buzz. And the next one will not either. This work shows up because paid support buys the one thing you cannot fake in a collapsing information economy: time. Time to read. Time to verify. Time to write clean. Time to correct myself in public when I get it wrong.

I do this night and day. My wife can tell you, I rarely sleep in a bed. It stifles my creativity. I’m writing a novel too, and when a line finally clicks at 2:30 a.m., the bed feels like a trap. So I end up on a couch, a chair, anywhere, like I’m back on duty grabbing rest where I can.

We do not need less of this kind of work. We need more. Deeper, more often, with better edits, stronger sourcing, and fewer unforced errors. And yes, I need help to scale upward, even if the first hire is the most obvious one in my house. Proofreading, fact checks, cleanup, the kind of quiet labor that makes the truth feel trustworthy.

That’s part of why this is late. This should have gone out five hours ago. I was still making corrections and additional edits so you could read this without feeling like you were stepping on nails.

So if you believe a free people cannot survive on cheap lies, and you want a place that tells the truth, stands up to mainstream narratives, and is willing to critique itself when it’s called for, become a paid subscriber.

And if you are already a paid subscriber, or you are on a fixed income, or you are tapped out right now, I see you. Absolutely no guilt. Absolutely no side-eye. You can still move this work.

Restack it. Share it. Text it to one person who actually reads. Drop it in a group chat where people argue in circles. Post it where the algorithm hates it. That is how truth travels when money is tight.

Sources

Dean Baker, “Debunking the Dumping-the-Dollar Conspiracy,” Foreign Policy (Oct 7, 2009): https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/07/debunking-the-dumping-the-dollar-conspiracy/

Jim Krane, “Exploring the Options: Arab Oil Exporters and the US Dollar,” Arab Center Washington DC (Jun 21, 2024): https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/exploring-the-options-arab-oil-exporters-and-the-us-dollar/

Faisal Islam, “Iraq nets handsome profit by dumping dollar for euro,” The Guardian (Feb 16, 2003): https://www.theguardian.com/business/2003/feb/16/iraq.theeuro

“Greenspan admits Iraq was about oil, as deaths put at 1.2m,” The Guardian (Sep 16, 2007): https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/sep/16/iraq.iraqtimeline

J. Soedradjad Djiwandono, “The Euro Factor in Iraq War?” RSIS Commentary (Mar 26, 2003): https://rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/564-the-euro-factor-in-iraq-war/

Avi Asher-Schapiro, “Libyan Oil, Gold, and Qaddafi: The Strange Email Sidney Blumenthal Sent Hillary Clinton in 2011,” VICE News (Jan 12, 2016): https://www.vice.com/en/article/libyan-oil-gold-and-qaddafi-the-strange-email-sidney-blumenthal-sent-hillary-clinton-in-2011/

ADST, “The Coup Against Iran’s Mohammad Mossadegh” (Jul 31, 2015): https://adst.org/2015/07/the-coup-against-irans-mohammad-mossadegh/

“Everything there is to know about Venezuela’s oil (and why US companies are ready for it),” We Are The Mighty(Jan 4, 2026): https://www.wearethemighty.com/feature/venezuela-oil-reserve/

U.S. EIA, “As much as 15 million barrels of crude oil sold from the SPR since December 2021,” Today in Energy(Oct 24, 2022): https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=54359

Reuters, “Trump says U.S. will run Venezuela after U.S. captures Maduro” (Jan 4, 2026): https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/loud-noises-heard-venezuela-capital-southern-area-without-electricity-2026-01-03/

Associated Press live updates, “Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro arrives in New York after capture by US forces” (Jan 3, 2026): https://apnews.com/live/trump-us-venezuela-updates-01-03-2026

“Saudi Arabia ‘open’ to petroyuan, closer China ties, minister says,” South China Morning Post (Sep 9, 2024): https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3277788/saudi-arabia-open-petroyuan-closer-china-ties-minister-says

YouTube video used in research, “The End of the Petrodollar? The Real Reason Behind the Venezuela Raid Revealed”:

YouTube video used in research, “$200 OIL IS HERE: The “ORINOCO BLOCKADE” That No One Is Watching”:

Federal Reserve History, “Nixon Ends Convertibility of U.S. Dollars to Gold and Announces Wage/Price Controls” (Aug 15, 1971): https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/gold-convertibility-ends

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, “Nixon and the End of the Bretton Woods System, 1971–1973”: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock

Federal Reserve History, “Creation of the Bretton Woods System”: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/bretton-woods-created

The American Presidency Project, “Address to the Nation Outlining a New Economic Policy: ‘The Challenge of Peace’” (Aug 15, 1971): https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-nation-outlining-new-economic-policy-the-challenge-peace

This is an excellent article. Thank you for producing it. I've been trying to learn about US oil production and trade recently and that effort leaves me with questions. I'm curious as to why US refineries were built to handle heavy crude. Was that the type of oil that the US produced through "normal" drilling (starting in the mid-to-late 19th century)? Your article notes that the shale oil we produce is lighter in quality than our refineries are able to handle without additional (and presumably costly) processing. So we export that. Apparently our refineries are able to handle oil like that produced in the Orinoco Belt better than that we now produce. Why is that so? We have been producing shale oil for decades by now. Why haven't we upgraded our refinery infrastructure. It's not as if oil companies are not making money. Could this be an effect of the financialization of much of American life?

As for our current intervention in Venezuela, I think the timing is intended to distract the public from the ongoing administration efforts to delay and minimize their mishandling of the Epstein files and the effects of the Jack Smith testimony. The overall basis is to reward the oil dinosaurs for their support of the administration and to further delay and obstruct the inevitable transition to non-fossil energy. I'm sure that's been in planning for quite a while. But as you note at the beginning, that surety is often something that survives the appearance of other facts (not "alternative facts," thank you)

Some interactive relationship maps to follow the petro dollars.

Blood, barrels and billions for MAGA donors from Trump's oil raid: Follow the money

https://thedemlabs.org/2026/01/05/trump-venezuela-oil-raid-maga-donors/

Petro-Politics: How Campaign Cash Fueled Trump’s Invasion of Venezuela

https://thedemlabs.org/2026/01/04/petro-politics-trump-venezuela-invasion-oil/

Mapping the jungles of Venezuela where Americans will die in Trump’s grift for oil

https://thedemlabs.org/2026/01/03/trump-invades-venezuela-for-oil/

What happened when America invaded Iraq for its oil?

https://thedemlabs.org/2026/01/03/venezuela-maduro-kidnap-trump-iraq-invasion-lesson/

Americans go hungry as Trump spends millions to invade Venezuela: Mapping the trade off

https://thedemlabs.org/2026/01/03/venezuela-us-military-strikes-maduro-trump-hunger-tradeoff