My future literary agent is going to want me to delete this.

Why? Because thinking out loud, in public, about the blueprint of a novel is supposed to depress demand. You’re not supposed to show the scaffolding. You’re supposed to let people imagine a heroic artist alone at a typewriter, catching lightning in a bottle like it’s a casual Tuesday, like some magical Negro Hemingway who just wakes up, stretches, and the Great American Novel falls out his sleeve with his lint. That myth sells. I get it.

Here’s the truth, though. I struggled. I stumbled. I circled the same scenes until they got dents in them. And yes, there’s shame in the fact that it isn’t finished yet despite the time I’ve set aside for it. Not because I don’t love the work, but because loving a thing doesn’t automatically build it. Discipline does. Structure does. And, apparently, so does swallowing pride and admitting you need witnesses.

So to my future agent, don’t panic. I’m not giving away the whole book. I’m telling you how it finally started moving. The greatest leaps of progress on War After War came when I opened it up right here and realized something I wasn’t expecting. People actually want to see this story on bookshelves. They want the receipts. They want the names kept. They want a novel that doesn’t just reenact history, but fights over who gets to remember it.

And that matters right now, because we are living in a moment where erasure isn’t an accident, it’s a strategy. A “clean” version of the past is being marketed like a product, and anything that complicates the Noble Lie is treated like contraband. If I’m building a book about the trap of payback and the long war for memory, then hiding the process like it’s shameful would be me cooperating with the very thing the book is trying to expose.

So no, this isn’t me “rambling.” This is me refusing to let the wrong people own the story.

The Good Crisis Made Me Go Back for Venus

I didn’t plan to reopen the manuscript and start moving load bearing beams around.

That’s not how writers like to tell the story of writing. We prefer the myth. The plot “arrived,” the characters “spoke,” the book “took over.” We like to act like we’re just standing under a waterfall with a bucket, catching genius. But The Good Crisis did what real crises do. It knocked the theater down. It made me look at what I was pretending not to see.

I went back into War After War and realized I had been doing what the country does.

If you are new here, let me say what the story is, plain. A formerly enslaved Black man named Alexander Freedmen survives the Civil War and the long counter insurgency that follows it. He lives long enough to become a problem for the people who want the past scrubbed clean. In the 1930s, two federal interviewers show up expecting a tidy veteran narrative. Instead they get a record of the wars America likes to call afterthoughts. The after is where freedom gets tested. The after is where terror returns in uniforms and in sashes and in polite language. The after is where a country decides whether citizenship is real or just a rumor.

The story moves in a straight line through time. It starts on a South Carolina plantation, then breaks into flight, then hardens into war. Alexander becomes a soldier in the United States Colored Troops and rides with Black men in blue into the liberation of Charleston under a banner that reads LIBERTY. Logan, the planter’s son turned Union lieutenant, serves in a different lane and ends up with Sherman. He lives up to his reputation as the brash officer who will confront authority, even in uniform. After Ebenezer Creek, when General Jefferson C. Davis abandons the freed people by pulling up the bridge, Logan tries to challenge him and fails, and that failure becomes a moral wound he carries. During the war, Venus moves differently. She becomes a quiet intelligence asset for the Union, relaying information from inside enemy-held spaces and listening rooms. The details stay deliberately spare here, but her role shifts from surviving power to bending it, using proximity and perception as weapons long before anyone would have called it espionage.

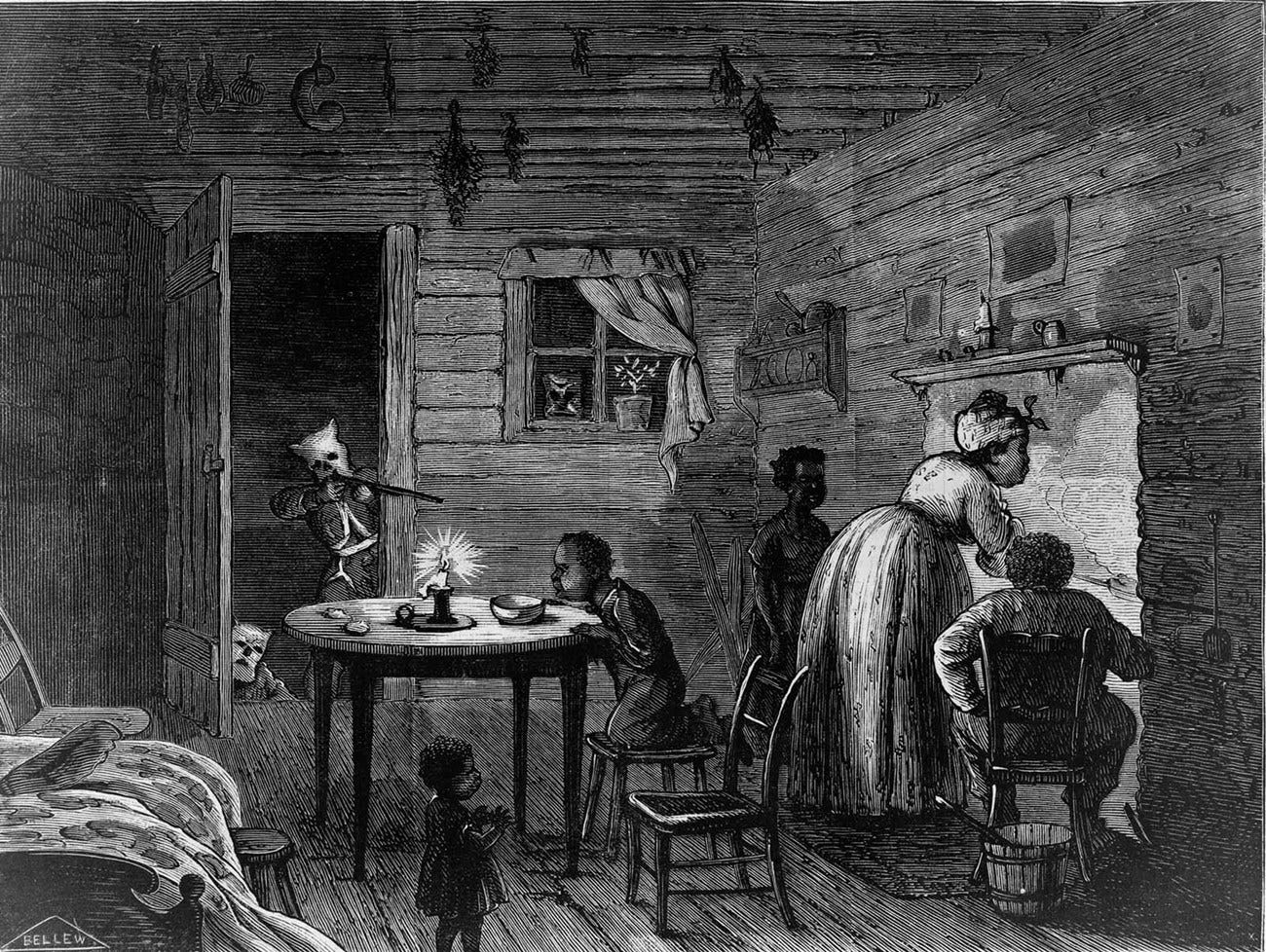

The shooting does not stop at Appomattox it only dampens into insurgency. The novel follows them into the War After War. Alexander and Logan are recruited as agents of the state, what we would now call federal agents, tasked with breaking up a multi state network of white militias composed of former Confederates who are determined to snuff out Reconstruction by attrition. Night riders, courthouse coups, assassinations, voter intimidation, guerrilla warfare waged not in open battle but through exhaustion and terror. That shadow war pushes them toward Wilmington, where the love triangle comes to a head and the country’s future gets decided in smoke. From there the fight shifts again into the propaganda war that tries to turn victims into villains. It’s a novel about what happens when payback feels like justice but ends up handing your enemies the story.

At the center is a triangle of survival, and it is also a love story. Not the clean kind. Not the kind built on fantasy. I want to show love in its purest form, which means female agency and consent, and I can only do that by showing what love looks like before power shatters it and what it takes to rebuild after.

There is an innocence early on. Two boys, Alexander and Logan, both sweet on Venus in that tender, awkward way kids are when desire is still mostly wonder. It is rivalry, yes, but it is also protection and loyalty and the first clumsy attempts at devotion. Then the rape happens and innocence does not just get bruised, it gets rearranged. The question becomes how you pick up the pieces without turning love into another form of coercion.

That is part of what the book is doing under the war story. It is showing people trying to reconstruct mating rituals free from domination. Trying to learn how to touch and be touched without taking. Trying to build a language for desire that does not sound like ownership. Black people have been trying to do that work for over a century in the shadow of what was done to us. That is why the blues exist. That is why quiet storm exists. That is why slow jams exist.

They are not just music. They are a people teaching themselves how to love when the world tried to train them to survive instead.

And that triangle comes to a head in Wilmington, where private devotion collides with public terror and where love, stripped of romance, has to prove what it really is.

I even have the cover in my head. Not as a demand, but as a north star. A field of uniforms and badges, not the glamorous kind, the kind that tells you institutions are present. A soldier’s silhouette. A law badge. Maybe a banner. Maybe a Bible pressed against ribs. The visual argument is the same as the narrative argument. The people who carry paper and people who carry rifles are fighting the same war. And to my future literary agent, relax. I’m not one of those authors who will hijack the process and micromanage the cover until everybody hates me. I’m giving you the shape of the feeling so the book doesn’t get dressed up in the wrong costume.

And here is the part that finally made me stop pretending this was just a personal writing problem. Every Civil War movie I grew up on gives you a slice. A battlefield here. A noble speech there. A charging line of men in blue, then a fade to black and a piano score that tells you the nation learned its lesson. Nobody connects the dots. Nobody takes you from the before, to the after, to the present, and shows you that the war did not end, it only changed uniforms.

I felt that absence in my gut the day over ten years ago I walked into the most renowned bookstore in my part of Florida and saw a whole wall devoted to Civil War battles. Antietam, Gettysburg, Shiloh, maps and muskets and generals, a museum gift shop of blood. Not one single solitary book on Reconstruction. Not one. The long fight to make freedom real was missing from the shelf like it never happened. That is not an accident. That is the memory war in retail form.

That is why this manuscript matters to me. It is not just the cannons. It is the policy. It is the insurgency. It is the propaganda. It is the present tense of the past. And it is also why I had to go back and face what I had left half in shadow. Venus was there, yes. A name. A presence. A future spy. But she was still orbiting male decisions, male guilt, male courage, male suffering. Which means I was repeating the very pattern I claim I’m trying to expose. Women turned into scenery in the story of power.

And then Minneapolis happened. And that line, those words, came through my screen like a bullet you don’t hear until you’re bleeding.

“fu*ki*’ b**h.”

Two words that are not just profanity. They are a permission structure. They are the sound of somebody who believes the law is a costume he wears when it benefits him. They are the sound of power unmasked, contempt with a badge on. I’ve been hearing it in my sleep because it doesn’t belong to one moment. It belongs to a lineage. It belongs to every era where the people with guns and uniforms and courts and newspapers decide they can speak to women like they are not human and still expect the world to call it order.

That’s when I understood something I had known intellectually but hadn’t let myself write all the way down into the floorboards of the book.

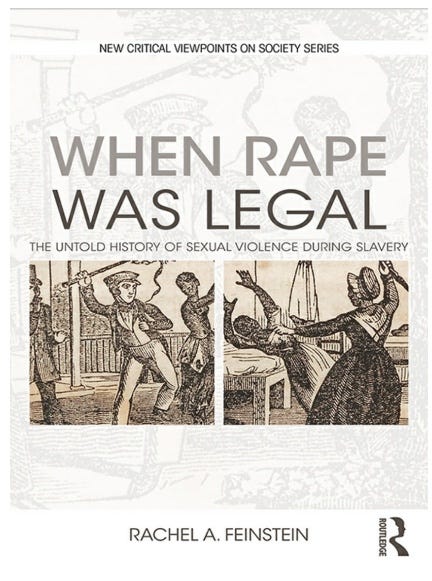

Rape isn’t a subplot in American history. It’s not a side effect. It is one of the engines.

On plantations, the routine sexual violation of enslaved women wasn’t “scandal.” It was policy without paperwork. It was the invisible clause inside the deed. A young girl “acquired” for “service” wasn’t a rumor. It was the dark half of respectability. In the daylight you parade her like decor, your cultured house servant, your proof you’re refined. At night you treat her like she’s a thing you purchased for use. Like she’s a… and here’s where the satire isn’t even satire because the truth is that ugly, like she’s a piece of furniture with a pulse. Like she’s a nightstand that breathes. Like she’s the property you can’t show company, but you can’t live without. And then you wake up the next morning, wash your hands, and sit in church like God is supposed to cosign the arrangement.

So yes, rape is the catalyst event in my story. I’m not worried about “giving too much away” by saying that. If anything, I’m naming the truth that too many Civil War narratives sanitize into manners, uniforms, and battlefield nobility. The war begins in the bedroom. The war begins in the lock on the door. The war begins in the moment a man decides another human being exists for his appetite and his silence.

My Auntie Mary character understands this because she lived it. In the world of the plantation she is the one who holds the people together, the woman who has buried children, stitched wounds, and learned when to speak and when silence is the only shield left. In a scene from the novel she prepares Venus not because she thinks it is right, but because she herself endured his assaults years earlier and survived by learning what the daylight would never admit about the dark. She knows exactly what happens when a young girl walks into that room unprepared and believes the lie that obedience will spare her.

That preparation scene matters to me now in a way it didn’t before, because it is the first place where the book tells the truth about what power costs, not in theory, but in flesh. And it matters that young Alexander overhears it. Because Alexander’s education doesn’t start with letters on a page. It starts with the understanding that the world has one set of rules in the daylight and another in the dark. It also mirrors what every Black man on that plantation had to hold inside himself, a contempt swallowed so completely it hardened into posture. The knowledge that a white overseer could take their women at any time without consequence, and that the only way to survive was to pretend it didn’t hurt. That lesson teaches boys how to bury grief, how to turn rage inward, how to learn silence as a kind of armor. Alexander hears that lesson too, and it shapes how he understands power, love, and what it costs to keep going.

Which brings me back to payback.

Because if rape is the catalyst, then payback is the most natural response. It’s the most human thing in the world to want to burn the whole plantation down and call it justice. It’s the oldest desire there is. You hurt mine, I hurt you. You take something from me, I take something from you. That’s why that Minneapolis moment and the spin that followed it hit me so hard. Not just because it’s cruel. But because it shows how fast institutions will try to normalize cruelty when cruelty serves power. And when cruelty gets normalized, the oppressed start dreaming of payback the way thirsty people dream of water.

But here’s the trap, this is the part my essay last night kept circling like a hawk over roadkill. Payback feels righteous, but it produces unforced errors. It leaves evidence. It leaves a crime scene. It hands your enemy the narrative weapon they’ve been begging you to give them. They don’t even have to beat you in a fair fight. They just have to point at the wreckage and say, “See? They’re animals. See? They’re violent. See? They’re the threat.” And then they use your reaction as the justification for their next round of repression.

That’s not a moral lecture. That’s a field report. That’s Reconstruction. That’s Wilmington. That’s the long American habit of provoking Black resistance and then using the resistance as proof that Black freedom was a mistake.

So The Good Crisis didn’t just inspire me to “give Venus a bigger role.” It forced me to admit the deeper thing. If this book is going to tell the truth about the War After War then it has to tell the truth about what begins the war inside the home. And if it’s going to tell the truth about payback, it has to show why the desire for it is understandable, and why, strategically, it can become the very mechanism that hands power back to the people who started the violence in the first place.

That’s the work now.

Not romance. Not nostalgia. Not bloodlust.

Record. Strategy. Memory.

If you don’t want to be enraged, stop here. Close this page.

Billionaire hedge fund manager Bill Ackman just dropped $10,000 into a GoFundMe for the ICE agent who shot Renée Good, then went on X to say he did it because he believes in “innocent until proven guilty.” Funny how that standard never seems to apply to Good. He also said he meant to give to her family too, but it was too late.

That GoFundMe was launched by Clyde Emmons, who bragged on Facebook that he did it because “the stupid c*nts wanna make a go fund me for that stupid bit** that got what she deserved.” A separate fundraiser for Ross rants that Mayor Jacob Frey is an “anti-American traitor” and adds “who is Jewish.” These are the people trying to turn her death into a payday.

Now take a breath. This is exactly how the trap of payback gets baited. They want the match strike. They want the outburst. They want the clip. They want the wreckage. They want to point at your anger and call it the problem.

So do the opposite. Choose persistent, informed, sustained action. Keep receipts. Keep names. Keep dates. Keep patterns. Support the work that stays alive after the Friday dump and the next distraction.

If you want to fight back in your own way, become an Author Room member. That buys me time to finish the novel, gives you exclusive excerpts here, and puts you on the list of the first 20 supporters who will be mentioned in the published book and receive a free copy when it releases. It also lets me walk into a literary agent or publisher meeting with proof that this book already has committed people behind it, not hypotheticals, not vibes, twenty real names who raised their hand early.

The cost is $99. And if that number makes you hesitate, just remember what you just read. Somebody out there treated $10,000 like pocket change for the man who killed her and then called her a “fuck** bi*tch.” Your $99 is not payback. It’s staying in the fight long enough to win the story. Scroll to Author Room below:

---> Here’s the truth, though. I struggled. I stumbled. I circled the same scenes until they got dents in them. And yes, there’s shame in the fact that it isn’t finished yet despite the time I’ve set aside for it. Not because I don’t love the work, but because loving a thing doesn’t automatically build it. Discipline does. Structure does.

~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~

I'm another writer. The creative / psychological landscape you describe is one I know intimately. (This is what "bleeding on the page" is all about.) I walk this territory every day in parallel with you.

I write this in the hope it helps you manage the inevitable angst that comes with this work ---> You're right where you need to be. Steady on. Keep moving. Even if it's in circles. You'll eventually find -- or carve -- or manifest the way out. What you describe in this essay is part of that. <3

“Every Civil War movie I grew up on gives you a slice. A battlefield here. A noble speech there. A charging line of men in blue, then a fade to black and a piano score that tells you the nation learned its lesson. Nobody connects the dots. Nobody takes you from the before, to the after, to the present, and shows you that the war did not end, it only changed uniforms.”

“That’s why that Minneapolis moment and the spin that followed it hit me so hard. Not just because it’s cruel. But because it shows how fast institutions will try to normalize cruelty when cruelty serves power.”

I’ve been reading your Substack for a week and subscribed after reading the first one (“PAYBACK ALWAYS LEAVES A CRIME SCENE”). I am deeply impressed with your profound understanding of both history and current events and how they’re related…always related. There’s really nothing new going on. We just keep repeating. But your clarity of that process seems to me to be part of how we begin to heal and reform and change. Awareness and honesty are often the catalysts for change. So much of what you write and explain should be obvious to everyone. I could have picked 4 or 5 things you wrote today that support that statement, but I chose just the two above. It’s one thing to report the news (and that’s important). It’s another entirely to understand society, human nature, and institutions the way that you do.

Thank you for the excellent work you do. It is a great service.