I Cannot Do This

It Don’t Hurt Now

Don’t worry, I’m not shutting this down or disappearing into anonymity. There are people who would love the tidy ending where I go quiet. They’re not getting it. I’m still here. I just can’t do the usual voice tonight.

I sat down to write like I always do. Cursor blinking. Draft folder open. The part of me that knows how to post reached for the clean take, the calm tone, the tidy landing.

This weekend didn’t let me do that.

What I watched reported out of Bondi Beach was violence aimed at Jews. What I saw about the shooting at Brown. Then the news about Rob Reiner and his wife. I named the events to myself like naming them was the same as facing them, then I turned back to the screen and the cursor kept blinking like it was asking me to get back to work.

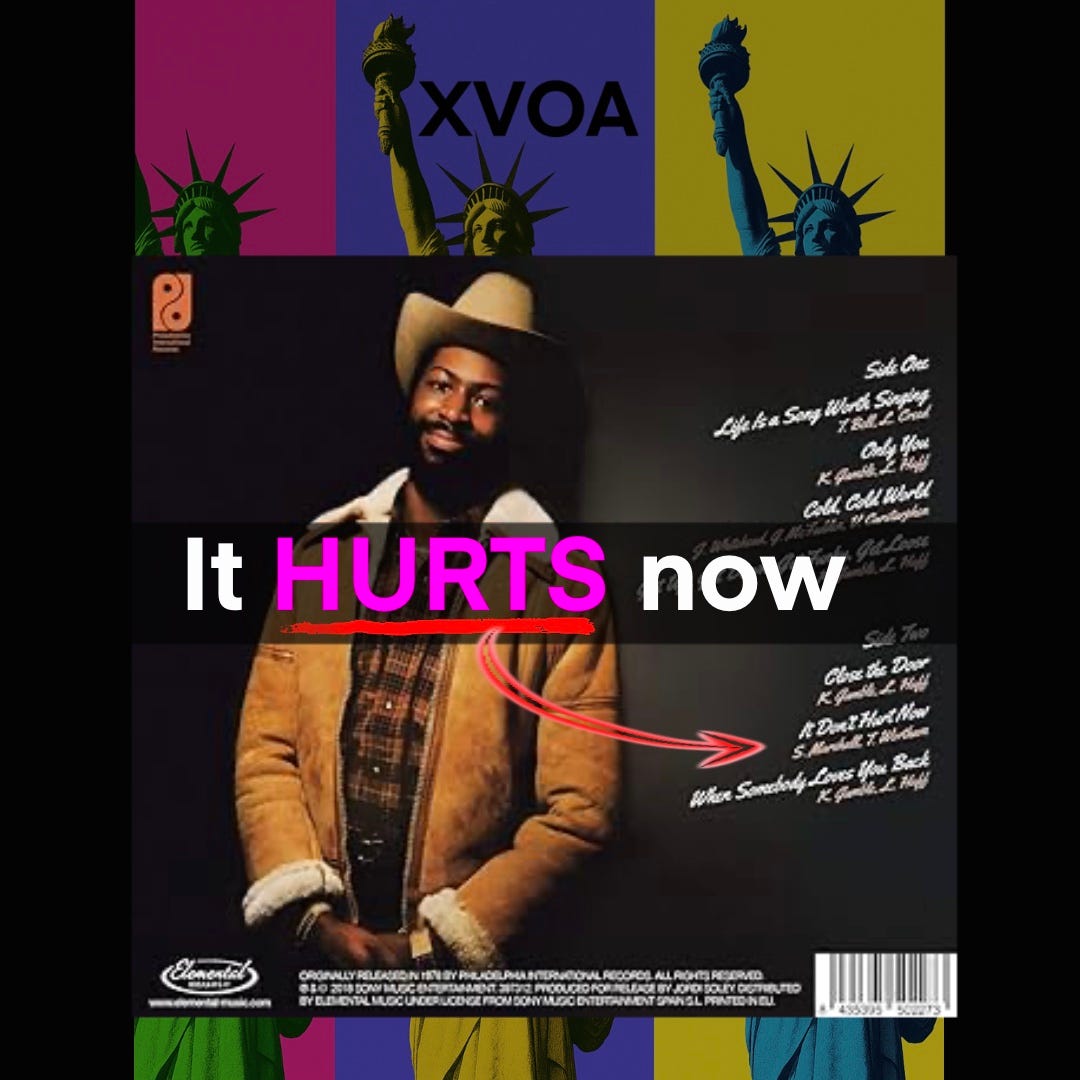

And then I found the song again, like an obsession. Why am I stuck on this line right now?

Teddy Pendergrass came through my speakers with that church-built phrasing you can hear in the bones of it, the kind of phrasing you don’t just learn in a studio. He came up in a Pentecostal Holiness world, preaching young, trained in the discipline of making a room feel something with nothing but breath and timing. That’s part of why I can’t shake the contradiction. This is that Teddy. The one who later did ladies-only concerts. The one with women throwing panties on stage. The whole grown-folks spectacle. And yet the delivery still carries that old pulpit muscle, the way a preacher can make even a “good news” line sound like a warning you’re supposed to take seriously.

I’m not going to do the whole history here. I’ll save the Thomas A. Dorsey-to-love-song blueprint for another day. What matters tonight is that weird, almost cynical tilt in the performance. Celebratory lyrics delivered solemnly, like he’s skeptical of the comfort he’s offering.

Then the hook drops and it feels less like relief than a tactic. It don’t hurt now. The cursor blinks. The hook repeats. It don’t hurt now. And I hear what I’ve been trying to do with the weekend itself. Call it fine. Call it manageable. Keep moving. Delay the moment I admit it is hurting.

That’s what denial sounds like when it gets good at its job. It turns into a rhythm. It turns into something you can repeat so your hands stay steady. And it’s not just a modern, online thing. People have always done this when the truth is too heavy to hold straight on. Sailors did it too, because out there you can’t afford panic, but you also can’t afford pretending forever.

Which is why I keep circling one story from the Southern Ocean.

Endurance

In August 1914, Ernest Shackleton pushed his expedition south with a plan that sounded like the kind of plan only confident men make. Take the ship Endurance into the Weddell Sea, land a crew on Antarctica, and attempt a crossing that would make history. The ship was built for ice. The crew was experienced. The provisions were real. The plan looked clean on paper.

Then the ice closed in.

And that’s the part that matters more than the hero-myth version. Nobody onboard woke up that first day thinking, “We’re going to lose the ship.” They did what grown professionals do. They adjusted. They normalized it. They convinced themselves it was temporary, because that’s what your nervous system begs you to believe when the alternative would force a full change of life.

They kept routines. They did work. They checked conditions. They made jokes. Not because it was funny, but because jokes keep panic from taking over the room. Out there, a laugh isn’t entertainment. It’s a pressure valve.

Meanwhile the ice kept pressing.

It wasn’t dramatic. It was patient. It didn’t argue. It just applied force until the ship began to speak in a language nobody could reinterpret. Wood complaining. Seams straining. The slow understanding that “built for this” doesn’t mean “immune to this.” That’s what breaks the mind, not the sudden catastrophe but the long middle where you keep telling yourself the thing can be saved while the evidence keeps stacking up against you.

Eventually the ship gave them the truth in a form they couldn’t tidy up. The plan wasn’t delayed. The plan was done.

So they stepped off.

Not with a triumphant speech. With decisions. With the ugly math of what you can carry and what you have to leave behind. You don’t bring everything. You bring what keeps you alive. And once you’re out there, standing on what used to be “unthinkable,” you learn a hard lesson fast. The thing you depended on can disappear, and you still have to keep breathing.

That’s why this story won’t leave me alone tonight.

Because my version of “the ship” isn’t wood and sails. It’s the part of me that knows how to stay composed. The part that can take in horror, convert it into content, and keep the schedule moving. The part that can say “I’m fine” with a straight face and a clean paragraph.

But this weekend felt like ice. Not one dramatic blow, but pressure, stacking, insisting, until the voice I normally use started to sound like a lie I was telling for comfort.

So when I saw the news, my first reflex was the same reflex I’ve been confessing all night. Look away. Minimize. Keep moving. Tell myself it don’t hurt now.

But it did. It landed like a sudden silence in a room that’s always had music playing. The kind of silence that makes you realize how much you were leaning on the sound.

And that’s when the whole “professional voice” thing started to feel like I was protecting the wrong vessel. I could feel myself trying to turn a death into a clean paragraph, trying to turn my sadness into a tidy observation, trying to keep the schedule safe from the truth. The problem is: if the work is supposed to mean anything, it can’t be built on that kind of avoidance. Not when the loss is personal, even if the person you lost never knew your name.

I keep seeing the same decision in a different uniform, and readers old enough to remember it will know exactly what I mean. Walter Cronkite at the desk, papers in hand, the most trusted voice in America, doing his job the way the country needed him to do it, steady and measured. And then came Vietnam, and the facts got too heavy to keep carrying in the same tone. People remember it as him basically saying, this war is lost. The words he actually put on the table were colder than that and maybe more devastating because they were so careful: “To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion.” You could hear it in the pause. You could hear it in the way the sentence landed. Not as performance. As admission.

That’s what I’ve been fighting. The urge to keep my voice.

Because “the voice” is how grown folks survive. The voice is how you go to work the day after bad news. The voice is how you answer texts when you’re not okay. The voice is how you sit at a keyboard with a blinking cursor and pretend you’re still in control of the story.

But the truth is the truth, and it keeps pressing like ice.

So I’m going to say it plain.

This weekend shook me.

Not in an abstract “I’m concerned about the state of the world” way. In a body way. In a sleep-won’t-come way. In a “I keep scrolling like I’m looking for a version of the story that won’t hurt” way. In a “Teddy is in my headphones telling me it don’t hurt now, and I know that line is a lie I’m trying to live inside” way.

And if you’re reading this with that tight feeling in your chest, that irritated restlessness, that quiet anger you can’t quite aim, let me name it for you. You’re not crazy. You’re tired of being asked to normalize what should never be normal. You’re tired of tragedies getting filed into the feed like weather. You’re tired of the way everybody’s expected to keep posting, keep working, keep smiling, keep joking, like the water isn’t rising.

You can feel it because I can feel it. That strain between what we’re told to accept and what our nervous system refuses to accept. That gap where the body is saying stop while the culture keeps saying move.

So I’m not doing the clean version tonight. I’m going to talk about what happened, one hit at a time, and I’m going to tell you what it did to me, because I suspect it’s close to what it’s doing to you, and somebody has to stop pretending that it don’t hurt now.

I can tell you what I did after each headline, because it wasn’t noble and it wasn’t unusual. It was the grown-folks reflex.

Bondi Beach hit first, and I watched my mind reach for the easiest story before I even meant to, the version that turns a tragedy into a permission slip to get a quick click. Then that other detail pushed through, the Muslim man who ran toward the danger and stopped it. That should have ended the cheap narrative right there. Instead, it made me sad in a deeper place than outrage reaches. Sad at what happened, and sad at how quickly people try to turn pain into a weapon. I stared at the screen, swallowed, and tried to move on. It don’t hurt now. I told myself. It don’t hurt now.

Then Brown. Students in the middle of ordinary life, stress, deadlines, the regular pressure of becoming somebody, and suddenly the whole place is a crime scene. That one tightened my chest because it exposed the lie we’ve been living inside. If you keep your tone calm enough, you can normalize anything. I felt that restless anger rise, the kind with nowhere clean to go. And I did what I always do when I don’t want to feel it. I reached for the next task. The next paragraph. The next “productive” thing. It don’t hurt now. Keep the schedule. It don’t hurt now. Keep moving.

Then Reiner and his wife, and my little system finally failed. Because that one wasn’t just “news.” That was personal weather. That was the soundtrack disappearing mid-scene. I felt the silence come into the room and sit down beside me. And for a second I tried the same trick again, turn it into a clean sentence, a tidy observation, something that would let me stay in the professional voice.

But the cursor kept blinking. The playlist kept going. Teddy kept singing. And the line I’d been using like armor started sounding like what it really is, denial with good timing. It don’t hurt now. A sentence you can live on until you can’t. It don’t hurt now until your body refuses to cosign it.

And if you’re reading this with that tight feeling, that irritated restlessness, that quiet anger you can’t quite aim, listen. That’s not you being dramatic. That’s you being awake. That’s your nervous system refusing to make peace with what shouldn’t be normal. You can call it “functioning” if you want. You can call it “being strong.” But you know what it is when you’re alone with the blinking cursor.

It hurts now.

It hurts now.

It hurts now.

So here’s the honest ask, and I’m going to say it the same way this whole piece has been said, plain.

If this hit you in that tight place, if you felt your own “it don’t hurt now” crack a little, don’t leave it trapped in your body like a private bruise. Move it. Share it. Let it travel.

Restack it.

Restack it for the person who keeps saying they’re fine too fast.

Restack it for the one who jokes right when you can tell they’re close to breaking.

Restack it because some of us need proof that we’re not the only ones refusing to normalize this.

And if you’re able, go paid.

Not as charity. Not as “support a creator.” As a trade. You help me buy time to keep writing with the mask off, and I keep giving you language for what you’re already carrying but haven’t been able to name. Because the machine will keep humming either way. The headlines will keep coming either way. The pressure to stay numb will keep pressing either way.

Paid subscriptions are how I stay in this seat, night after night, and keep telling you the truth your body already knows.

It hurts now.

It hurts now.

It hurts now.

If this hit you in that tight place and you felt your own “it don’t hurt now” crack then restack it. Send it to the person who keeps saying “I’m fine” too fast.

Also if you’re able, go paid. http://www.Xplisset.com/subscribe Not as charity but as a trade: you buy me time to keep writing with the mask off, and I keep giving language to what you’ve been carrying.

It hurts now.

This reminded me me of what a douche I feel like when I go to the wake for a child who died from a brain tumor . . . or a teen-ager who died in an auto accident . . . or a young adult who overdosed. Ive studied what NOT to say. #1, for the lucky ones who aren't parents or siblings in one of the aforementioned scenarios: "I'm so sorry. I know just how you feel." Or the fucking platitude of "Time heals all wounds." So . . . I usually just hug the person and say, "I love you."

In this case, I think we are all (at least the ones who follow you) in pain. We all mourn the irreplaceable hole President Wrecking Ball and the government bullshit that ignores the power of a gun to kill continues to leave. So, in this regard, we are one. We do understand.

Thank you for putting into words what so many of us only wish we could articulate. In doing so, we feel just a little better. A little more capable of moving to the next whatever. And--best of all--a little more human.